The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor: Delays Ahead

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 7

By:

Introduction

Although no new deals were struck during People’s Republic of China (PRC) President Xi Jinping’s trip to Myanmar on January 17 and 18, the visit was significant for several reasons. The visit was the first by a PRC president to Myanmar in 19 years, and the first by Xi to this country in his role as president. The visit was widely touted as marking the 70th anniversary of the establishment of relations between the PRC and Myanmar. However, Xi’s first trip abroad this year was aimed at expediting implementation of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), a key component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (CGTN, January 17). During the visit, the two governments signed 33 agreements, memorandums of understanding, protocols and letters of exchange relating to railways, industrial and power projects, and trade. Several of these agreements firm up Myanmar’s commitment to the CMEC’s three central components: the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ), which includes a deep-sea port, an industrial park and other projects; the China-Myanmar Border Economic Cooperation Zone; and an urban development plan for Yangon (The Irrawaddy, January 18).

However, just weeks after Xi’s visit saw the two sides take steps to expedite CMEC projects, Beijing’s plans have run into new problems. CMEC projects are running late, and in an op-ed piece published on the eve of his Myanmar visit, Xi stressed the need for CMEC projects to be moved from “the conceptual stage to concrete planning and implementation” (New Light of Myanmar, January 16). The coronavirus pandemic has emerged as the latest challenge in the long list of obstacles that have slowed CMEC projects over the years. According to Khriezo Yhome, a New Delhi-based analyst of developments in Myanmar, it “may be too early to assess the impact of the coronavirus crisis on CMEC projects,” given that the pandemic is still only at an “initial phase” in Myanmar; however, there is “no doubt” that it “will slow down the implementation of CMEC projects in the short-term.” [1]

The CMEC is a Major Priority for China

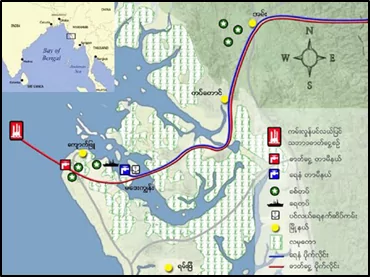

The 1,700 kilometer-long CMEC runs from Kunming in China’s Yunnan province to Mandalay in central Myanmar, where it then forks both southward to Yangon and westward to Kyaukphyu. Kyaukphyu, which is CMEC’s maritime gateway, has enormous strategic value given its location on Myanmar’s Bay of Bengal coast. CMEC is expected to bestow China with immense economic and strategic benefits. It provides landlocked Yunnan province with access to the sea and will boost its economy. Importantly, successful construction of the CMEC would also strengthen China’s presence in the Indian Ocean. It would offer imported products from South Asia, West Asia, and Africa with a shorter route to the Chinese mainland, thereby cutting transport time and costs. China’s trade is already drawing on some of these benefits: gas and oil have been transported via pipelines on this route since 2013 and 2017, respectively. CMEC will reduce China’s dependence on the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea, thus lessening its vulnerability to oil imports and other trade from being choked off by hostile powers in the event of a conflict. CMEC’s completion is therefore a priority for China.

Consequently, Beijing has been pushing Myanmar to speed up implementation of CMEC projects. Its leverage to do so has increased over the last couple of years, as Myanmar’s relations with the West have deteriorated over alleged atrocities against Rohingya Muslims. The Myanmar government also faces allegations of genocide in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague. As international pressure on Myanmar increases its dependence on the PRC for diplomatic and other support, ties between the two states have deepened. This has accordingly opened up space for Beijing to nudge Naypyidaw on project delivery. Xi’s visit, which came just a little over a month after State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi defended her government at the ICJ, seems to have been timed to take advantage of this opportunity. It was the “right moment” for him to push Myanmar to deliver on its project commitments (Observer Research Foundation, January 16). Given the priority it accords to CMEC and the inordinate delays in decision making and implementation on the part of Myanmar, Xi’s focus on expediting projects was to be expected.

Costs and Concerns

Many in Myanmar recognize the potential benefits of CMEC projects. They recognize that CMEC offers Myanmar the opportunity to modernize its decrepit infrastructure, which is essential for economic growth (China Brief, September 19, 2018). It is also seen as having the potential to create jobs for Myanmar’s youth and to boost its trade (Frontier Myanmar, September 26, 2018). Still, the Myanmar government is taking a cautious approach to CMEC projects, and their high cost has been an issue of major concern. The Muse-Mandalay section of a planned railway project will cost almost $9 billion (The Irrawaddy, May 14, 2019); the New Yangon City project carries a price tag of $1.68 billion (Frontier Myanmar, March 8, 2019); and the Kyaukphyu port was originally pegged at $10 billion ($7.3 billion for the port and $2.7 billion for the SEZ).

Project price tags have prompted experts to question the need for Myanmar to pursue such expensive projects, and to question their economic viability (Myanmar Times, November 15, 2019). The Kyaukphyu port, for instance, will bring only limited returns to Myanmar unless the accompanying SEZ attracts significant business and flourishes. However, that seems unlikely given Kyaukphyu’s distance from Yangon and other commercial hubs (Observer Research Foundation, January 14). Moreover, there are fears that costly projects would increase Myanmar’s debt burden—and given its extreme dependence on China, push the country into a “debt trap” of the sort experienced by Sri Lanka (Mizzima, March 7; China Brief, January 5, 2019). Additionally, local communities are apprehensive that mega-projects will cause environmental degradation and mass displacement of locals. The Kyaukphyu project, for instance, has evoked strong opposition from local fisherman and farmers, who fear that fishing restrictions and the acquisition of land by the government will result in loss of their livelihoods (Mizzima, December 8, 2019).

Delays in Decision-Making

Several of the apprehensions that CMEC projects have evoked in recent years are similar to the questions that were raised with regard to the $3.6 billion Myitsone hydropower project. Activists in the Kachin State (where the project was to be located) have argued that while 90% of the electricity generated was to be sold to China, they would suffer loss of livelihoods and end up bearing the costs of environmental degradation. Massive protests erupted, forcing Myanmar’s then-President, Thein Sein, to suspend the project in 2011. Currently, the project remains suspended—and should Myanmar ultimately decide to cancel it, it will have to not only compensate China but possibly suffer political blowback for that decision. The government cannot cancel the project on account of the implications it would have for Sino-Myanmar relations—but it cannot revive it either, as that would provoke mass unrest across the country (China Brief, April 24, 2019).

The Myitsone experience has prompted Myanmar’s present government to move cautiously on CMEC projects. It has avoided closing deals swiftly or simply endorsing Chinese proposals. Approvals are given to only those Chinese project proposals that conform to Myanmar’s priorities, policies and procedures. Consequently, just a fraction of proposed projects have been approved so far (Frontier Myanmar, May 24, 2019). Of the 30 project proposals that China put forward, Suu Kyi reportedly signed just nine CMEC “early harvest” projects during the second Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in April 2019 (Frontier Myanmar, September 26, 2019).

The Myanmar government has renegotiated project terms, trimmed down projects, and bargained hard to bring down costs. The Kyaukphyu port project, for instance, has been scaled down to include just two berths from the originally planned ten. Its cost has been slashed by 80% and the China-Myanmar holding ratio was brought down from 85:15 to 70:30 (Myanmar Times, July 12, 2018). Myanmar’s hard bargaining with China has taken time, but it has been able to change project terms to better suit its interests and development priorities.

Small Steps Forward

While bureaucratic red tape has always slowed the pace of decision-making in Myanmar, enhanced scrutiny of CMEC project proposals under the National League of Democracy government has further added to delays. However, while Myanmar’s decision-making and implementation of projects may not be going according to Beijing’s plans or timetables, things are moving forward, albeit slowly. This is evident even with regard to the highly controversial Kyaukphyu port. Although rights activists continue to raise objections to the environmental and social costs of the project, differences between the Myanmar and Chinese governments “have been resolved at least on paper over financing of the project and scale of the project to be developed in a phased manner,” after the Myanmar government renegotiated project terms in 2018 and following Xi’s recent visit to Naypyidaw. [2]

During Xi’s visit, the two sides signed a concession agreement and a shareholders’ agreement relating to the Kyaukphyu project (The Irrawaddy, January 18). In the weeks that followed, a consortium led by China’s state-owned corporation CITIC indicated intent to initiate bidding for an environmental impact assessment (EIA) consultant for the Kyaukphyu port project (Myanmar Times, March 11).

Coronavirus Strikes

However, whatever momentum Xi’s visit may have provided to CMEC projects could wane in the coming months, with the coronavirus pandemic posing new challenges. Implementation of CMEC projects is unlikely to escape the devastating impact of the coronavirus pandemic. So far, the pandemic has not hit Myanmar as hard as it has either China or its other neighbors. Still, the pandemic has already dealt a blow to Myanmar’s economy since China dominates the country’s tourism, trade, agricultural, and industrial sectors. Supply lines have been disrupted and have impacted agriculture, aquaculture, and seafood sectors. Chinese businessmen have returned home taking their equipment and machinery with them (Frontier Myanmar, February 19). The shutting down of border crossings and trade has cost Myanmar dearly: since January 27, it is said to have lost trade worth $8 million per day via the Muse border gate alone (The Irrawaddy, February 11).

Although Myanmar has a roughly 2,200 kilometer-long border with China and has almost a million Chinese visiting annually, coronavirus infections have so far come primarily from Western countries, and not China. However, anti-Chinese sentiments have always been strong in Myanmar and could surge—even violently—if cross-border infections were to rise in the weeks ahead. Violence targeting Chinese workers in Myanmar could trigger an exodus that would likely impact project implementation. Beijing appears eager to head off such problems in Myanmar by spreading a positive message about its global outreach, and has sent a team of medical experts and supplies (masks, gloves, overalls, and testing kits) to Myanmar (CGTN, April 8).

Conclusion

The Chinese government has begun acting to normalize economic engagement with Myanmar: for instance, customs clearance at trading posts along the Sino-Myanmar border has been eased, and border trade has been revived (Eleven Myanmar, April 3). According to PRC Ambassador to Myanmar Chen Hai, Beijing has reaffirmed its commitment to “carry on” with all “agreed-upon [CMEC] investments and projects… despite the impact of the coronavirus” crisis. However, projects that need “exchanges between technical staff” of the two countries “may be impacted” (Myanmar Times. March 30).

It is likely that, as the coronavirus crisis in Myanmar worsens, momentum on CMEC projects could wane. The Myanmar government can be expected to focus on dealing with the viral outbreak and preventing its spread, as well as limiting the pandemic’s impact on livelihoods. Work on the projects could take a backseat for some time. As for China, it “may want to keep the focus on humanitarian assistance in the immediate-term.” [3] Preoccupation with the coronavirus’ deadly impact could therefore see the two governments put CMEC project implementation on the backburner in the coming months.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bengaluru, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political and security issues for The Diplomat, Asia Times, and the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

Notes

[1] Author’s interview with Khriezo Yhome, research fellow at the New Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation’s Neighbourhood Regional Studies Initiative, April 4.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.