Captive Nations Week Marked for First Time in Ukraine

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 115

By:

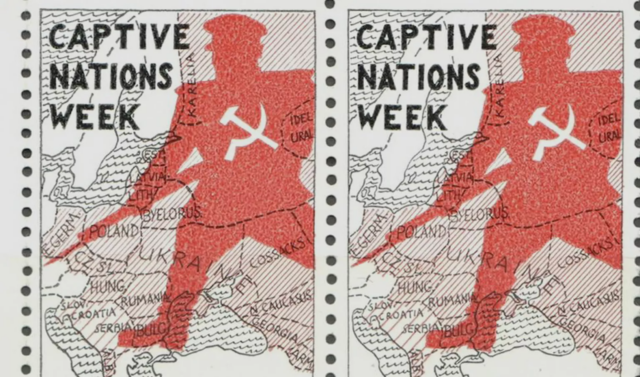

When the United States Congress passed a resolution in 1959 requiring the president to issue a proclamation on Captive Nations Week every July, this measure was viewed both by its authors and those opposed to it as directed against the repression of nations by communist regimes. Until the collapse of the Soviet bloc and then the Soviet Union itself in 1989 and 1991, respectively, these messages served as indicators of how the US government viewed these communist regimes. In the years since, the messages have celebrated the freeing of nations in the former communist states and focused on nations that remain under communist rule. But many of those participating in these commemorations have spent more time celebrating past victories than talking about current challenges. Many others have been dismissive of the continuation of this project as such.

That is perhaps understandable because of how much progress has been made in combating repression; even so, these celebrations miss the point. On the one hand, they ignore the fact that the Captive Nations Week resolution focused not on communism as a doctrine but communism as a practice, which involved repression not limited to communist states. Victories over communism have led to real advances. However, many who proclaimed themselves as non-communists or even anti-communists have continued or revived the kind of ethnonational repression that the Soviet communists carried out in the past and that other surviving communist regimes, China first among them, are carrying out to this day. On the other hand, focusing on communist regimes alone obscures just how many atrocities are being carried out by nominally non-communist regimes and how much work remains to be done in countries like the Russian Federation. There, for example, two of the captive nations the 1959 resolution spoke of inside Russia, Idel-Ural and Cossackia, remain hopeful for liberation (see EDM, November 19, 2013; February 21, 2019).

In his proclamation of Captive Nations Week a year ago, US President Joe Biden sought to correct this trend and returned to the principles underlying the original resolution’s concerns about the victims of imperialist oppression, regardless of how those carrying it out would characterize themselves (Whitehouse.gov, July 15, 2022). Biden made three key points: First, Captive Nations Week is not about anti-communism per se, but rather, against all forms of repression. Only three of the regimes he listed among the world’s most repressive are communist—Cuba, North Korea and the People’s Republic of China. The other six are either former communist countries or have never been communist—Russia, Iran, Belarus, Syria, Venezuela and Nicaragua—and the US president listed Russia first among these countries, not because of its communist roots, but because of its continuing imperialist behavior.

Second, Biden was explicit that governments that repress their people at home, as all nine of these countries do, seek to repress others abroad through aggression. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the most obvious case of this. And third, and this may be the most important aspect of his declaration last year, Biden made clear that Americans cannot remain unconcerned about such repression, be it within countries or between them and their neighbors. They must “stand in solidarity with the brave human rights and pro-democracy advocates around the world” (Whitehouse.gov, July 15, 2022).

The US leader concluded with the following words: “May Captive Nations Week reinvigorate our efforts to live up to our ideals by championing justice, dignity and freedom for all,” words that apply not only to communist countries but also to post-communist countries, states that have never been communist and the United States. Biden did not say it directly, but his words clearly imply something that has often been forgotten: We are anti-communists not because people call themselves communists; we are anti-communists because of what communists have done.

This year, the reinvigoration of the principles behind Captive Nations Week has continued and expanded. In his proclamation issued on July 14, Biden devoted particular attention to “Russia’s brutal aggression against its neighbor Ukraine” and “the Ukrainian people’s courageous defense of their sovereignty, freedom, land and lives.” He concluded that the actions of Ukrainians and others who champion democracy “are living proof that the darkness that drives autocracy can never extinguish the flame of liberty that lights the souls of free people everywhere” (Whitehouse.gov, July 14). And perhaps representing an even more critical development, for the first time ever, Captive Nations Week is being marked not just in the United States but in Ukraine as well, itself a former captive nation and a current victim of imperialist aggression.

Ukraine has particular reasons for taking the lead: Kyiv sees the non-Russians in Russia as its allies against Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine on the basis of the principle that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” And last week, at a meeting hosted by two Verkhovna Rada deputies, representatives of the Erzya, Oirat-Kalmyk, Sakha, Ingush, Dagestani, Buryat and other submerged nations within the current borders of the Russian Federation came together and declared Ukraine must become a center of support for the non-Russian nations there. They called for support in “the division of the Moscow empire into individual nation states” and thereby “guarantee the security of Ukraine and the entire civilized world” (Abn.org.ua, July 10; Abn.org.ua, July 11).

This action by Kyiv is the latest example of Ukrainian efforts to support non-Russian peoples within the borders of the Russian Federation. (For background, see Window on Eurasia, December 9, 2018; April 17, 2019.) Indeed, already at the end of 2022 in particular, Ukraine took two pages from the American Cold War playbook about captive nations: its parliament called for the international recognition of the right of the peoples of Russia for self-determination and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy referred to Putin’s Russia as an updated version of the evil empire. The first of these echoed the 1959 US Congress Captive Nations Week resolution but goes even further by denouncing Moscow for carrying out acts of “genocide” against the non-Russians in Russia, including through the use of selective mobilization (Itd.rada.gov.ua, October 6, 2022). The second, by Zelenskyy, recalls the words of US President Ronald Reagan, who in 1983 described the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” (see EDM, October 13, 2022).

Moscow has long been dismissive of the American Captive Nations Week resolutions, suggesting they are “survivors of the past” that should be cast into “the dustbin of history” (see EDM, January 18; June 8; Ukraina.ru, May 12). Even so, Russia’s leaders are clearly worried about them (Aif.ru, January 11)—and they will find it harder to dismiss what Ukraine is now doing, especially because Kyiv’s actions are another sign of the solidification of its ties with the West.