Lukashenka’s 30th Presidential Anniversary Highlights Belarus’s Political Divide

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 112

By:

Executive Summary:

- Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka celebrated the 30th anniversary of his rule on July 10, highlighting his enduring influence in Belarusian politics as the country’s only president since independence.

- Lukashenka’s power relies on pro-Russian support against pro-European factions, which he claims necessitates authoritarian control. Belarusians who favor Russia seek national unity, while pro-European Belarusians seek higher living standards and the rule of law.

- The West can support the opposition, Lukashenka, or both, as strengthening ties with Lukashenka could serve to shift Belarus further from Russia through providing him economic and diplomatic alternatives to the Kremlin.

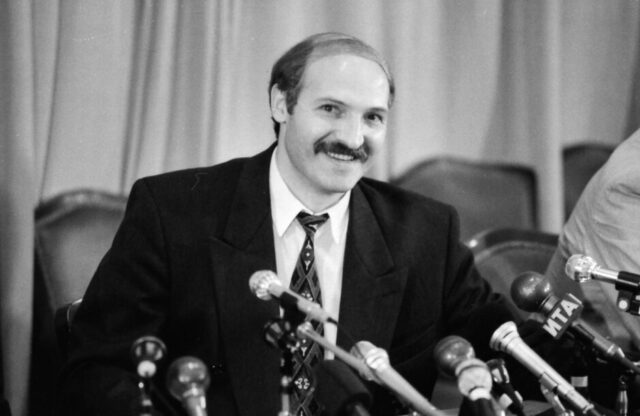

July 10 marked the 30th anniversary of Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s victory in the second round of the 1994 presidential elections, where he received 80.34 percent of the popular vote. While fraud was never suspected in 1994, it has been in all subsequent elections (2001, 2006, 2010, 2015, and 2020). According to surveys conducted by the Independent Institute for Socio-Economic and Political Studies (IISEPS), one Belarus’s most reputable sociological firms until its forced closure in 2016, Lukashenka used to win elections with a smaller margin than reported. For example, in 2010, IISEPS estimated Lukashenka’s share of the popular vote at 58 percent, whereas official data claimed it to be about 80 percent (RIA Novosti, December 24, 2010; NMN, January 11, 2011). The results of the 2020 elections—a highly implausible 80.8 percent for Lukashenka and just 10.09 percent for Svetlana Tikhanovskaya—are suspected to be blatant fabrications (see EDM August 10, 2020, January 25, 2021). Regardless, Lukashenka has ruled Belarus for 30 consecutive years, evoking drastically different reactions across the political spectrum. Lukashenka’s prolonged rule over Belarus has shaped the country into what it is today. His close relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin keeps Minsk by and large under the Kremlin’s control. At the same time, the Belarusian opposition is hoping to move Belarus toward the West, while the population seems split between both camps (see EDM, January 19, 24, March 20, May 30, June 13).

Belarusian media reflected this split stance in their mixed reactions to the anniversary. A series of articles titled “Alyaksandr Lukashenka: 30 Years of Citizens’ Trust and State Governance” in Belarus Segodnya, the country’s major official daily, highlighted that “Belarus has moved from the group of countries with a low level of human development to a group with a very high level, where it has confidently occupied its position for more than ten years.” The central thesis is that Lukashenka resisted the temptation of the 1990s to “get rid of the economic burden—free medicine, education, and other social benefits” because “the invisible hand of the market would regulate everything by itself.” Newly formed parties and movements aided by Western funds popularized these “dangerous” ideas, which settled in most post-Soviet republics and lobbied for the “sale of everything to private hands” (Belarus Segodnya, July 11).

The anti-Lukashenka reaction among Belarusians came primarily from abroad. Harsh reactions came particularly from Poland and Lithuania, where most pro-Western Belarusian activists now reside since fleeing the country following the crackdown on the 2020 post-election protests and the government jailing many of their comrades (see EDM, September 15, 22, 28, 2020, August 16, 2023). Iryna Khalip, a popular Belarusian journalist in the 1990s, suggests that Lukashenka’s 30 years in power have been a tragedy for the Belarusian people and a stroke of luck for Putin. To Khalip, Lukashenka is uncouth, while Putin is more sophisticated, yet both are presidents of rogue states. Despite their differences, the Belarusian journalist contends, “their relationship transcends conflict, Putin’s disdain, and Lukashenko’s animosity. Their familial bond has brought them together as a singular evil” (Novaya Gazeta, July 10).

One way to evaluate Lukashenka’s anniversary is through the lens of a lasting cultural and geopolitical division within Belarusian society. Multiple IISEPS surveys have highlighted this phenomenon (Ideasbank, September 5, 2022). From this perspective, two facts stand out. Lukashenka appears to lead a more entrenched pro-Russian community, and his longevity in power is partly due to a tug-of-war between this community and the pro-European one. For Lukashenka, this has necessitated strong authoritarian control lest the “perfidious” Westernizers steal Belarus from itself and from Russia. While the balance between the pull of Russia and Europe has varied over time, there is a key difference in Belarusians’ attitudes toward these external centers of power. As Belarusian political scientist Artyom Shraibman once highlighted, “The good attitude of Belarusians toward Russia does not stem from the economy or propaganda but rather from a deeper sense of unity and community. … Pro-European-minded Belarusians choose their side based on rational considerations. They speak of a higher standard of living, education, healthcare, and the rule of law in the European Union. But Belarusians who choose Russia attribute their choice to more metaphysical arguments such as ‘these are our brothers’ and ‘we are the same’” (Zerkalo, January 18, 2023).

Before the 2020 Belarusian presidential elections, Belarus’s closeness to Russia did not negate Minsk’s agency. This was also before the Kremlin came to Lukashenka’s aid against mass protests and the levying of stringent Western sanctions against Minsk. Examples of this include Minsk’s rejection of a Russian military base on Belarusian soil and the effective eviction of the Russian ambassador for the officially articulated reason that he routinely confused Belarus with a federal district of Russia (see EDM, May 7, 2019; Izvestiya, October 3, 2019). Since 2020, Belarus has still demonstrated smaller examples of agency, such as the introduction of a visa-free regime for citizens of 35 European countries from July 19 until the end of the year (Belarusian Foreign Affairs Ministry, July 17). This regime, in addition to visa-free entry for Polish, Latvian, and Lithuanian citizens, was first introduced in 2021. “Against the backdrop of new discriminatory measures from the Baltic countries and the recent EU sanctions package against Belarus and Belarusians, such actions of Minsk reflect the imagination of the ‘last dictatorship of Europe’ and a lack thereof on Europe’s side, which is depressing,” writes Pavel Matsukevich, a former Belarusian diplomat now at the Warsaw-based Center for New Ideas, a Belarusian opposition think tank. He adds that the visa-free regime for Europeans “indicates the preservation of a certain autonomy of Belarus’s foreign policy despite its dependence on Russia” (NewBelarus July 19). Moscow does not practice anything like this and has faulted Minsk for such steps in the past. In other words, Minsk is trying to remain somewhat open to the West under the current circumstances.

Belarus’s geopolitical orientation is still in limbo, drifting between the West and Russia. Those in the West who look to move this geopolitical orientation away from Russia have several options. First, Western governments could maintain relations exclusively with the Europe-based Belarusian opposition and sponsor it for moral reasons, in the hope that it would eventually seize power in Minsk. Second, they could maintain relations exclusively with Lukashenka’s milieu, which has controlled Belarus’s destiny for 30 years and will most likely continue to do so after Lukashenka’s death or retirement. Third, they could maintain relations with both the opposition and the Lukashenka-led regime, hoping to find a balance between the two. Russia has effectively taken the second option. The West currently engages in the third option, but its policies are overly close to the first option. The number of European emissaries in Minsk is often short of an ambassador, while the United States does not even have diplomatic staff in the Belarusian capital. Strengthening relations with Lukashenka and his regime while maintaining contact with the opposition may be useful in pulling Belarus further away from Russia’s grasp and into the Western sphere.