Al-Qaeda’s Purpose in Yemen Described in Works of Jihad Strategists

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 4

By:

It appears that al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) is currently following a new version of a classic al-Qaeda strategy. Developed by al-Qaeda’s strategic thinkers, the strategy behind AQAP’s latest operations is to draw American military forces into Yemen. If successful, AQAP would strengthen its position in the near term within the traditional tribal structure and potentially benefit its recruitment efforts and broaden its financial support. Such an outcome would also open another front in a strategic location, even as the United States is planning and executing a drawdown in Iraq. In light of the United States’ current refusal to take this bait, we should expect AQAP to attempt further provocative operations aimed at America.

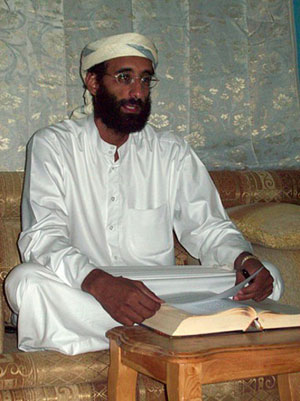

In October 2009, Shaykh Anwar al-Awlaki published an article in English on a jihadi website with the title: “Could Yemen be the Next Surprise of the Season?” (tawhed.ws, October 20, 2009). Born in the United States, this is the same ideologue who was linked to Major Nidal Hassan, the Fort Hood shooter, and the young Nigerian who attempted to blow up Northwest Airlines Flight 253 en route to Detroit on December 25. Very little notice was taken of this article in the Western press initially, perhaps because Al-Awlaki gave no details and had not yet achieved his current notoriety, but he did make some telling points.

Al-Awlaki, a resident of Yemen, did not call for jihad against Yemen’s president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, who is both a Zaydi Shi’a and the long-serving secular ruler of the Republic, even though the Shi’a and secular governments are often targets of al-Qaeda. Instead, his focus was on jihad against America and the Saudi royal family. Yemen has had a mixed relationship with al-Qaeda, ranging from intense security operations aimed at destroying the organization to periods of relative quiescence. Although al-Qaeda in Yemen has attacked government forces, its main focus has been foreign targets. [1] Al-Qaeda members based in Yemen began anti-U.S. operations over ten years ago with the attack on the USS Cole on October 12, 2000, in which 17 Americans were killed and 38 wounded. More recently, the group was responsible for the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 on December 25, 2009. [2] The successful attack on the USS Cole prompted a determined campaign by the government of Yemen and the United States against al-Qaeda in Yemen, including the killing of local leader Abu Ali al-Harthi by a Predator strike in 2002. It appeared to most observers that by 2004 the government of Yemen, with American help, had rendered al-Qaeda in Yemen relatively powerless. The reemergence of al-Qaeda as the player it is today began in 2006, when 23 jihadists escaped from prison in the Yemen capital of Sana’a. Among the escapees was a former aide to Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, Abu Basir Nasir al-Wuhayshi, who was later to become the leader of al-Qaeda in Yemen (see Terrorism Monitor, March 18, 2008). At least two former inmates of Guantanamo were among the escapees who later became local al-Qaeda leaders (Asharq Al-Awsat, Dec. 29, 2009).

A Base for al-Qaeda?

Yemen presents al-Qaeda with ideal conditions in which to operate. The government is hard pressed on all sides. It is battling an insurgency by the Shi’a minority “Houthi” faction in the north along the border with Saudi Arabia. Houthi incursions into territory claimed by the Kingdom drew a sharp Saudi military response starting in November, 2009, amid near-universal Arab claims that Iran is supporting the rebellion to destabilize the Arabian Peninsula (Asharq al-Awsat, December 13, 2009). Unrelated to the Houthi rebellion, a simmering al-Qaeda-endorsed secessionist movement in the south presents another challenge. Yemen’s economy appears to be locked in a downward spiral with declining oil reserves and a severe shortage of water. The nation is also facing massive unemployment in the context of a dramatically increasing population.

The January 2009 consolidation of the two branches of al-Qaeda in Saudi Arabia and Yemen into al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) was likely a practical move, prompted by the increasing success of Saudi security forces inside the Kingdom and by consequence need to take advantage of a safe haven in Yemen (see Terrorism Monitor, September 11, 2009). Saudi officials became concerned about the presence of al-Qaeda in Yemen as increasing numbers of Saudi al-Qaeda members began to migrate south. After AQAP was formed, Saudi officials published a list of the 85 most wanted members of al-Qaeda, most if not all of whom were believed to be operating out of the Yemen safe haven. Meanwhile, Saudi forces continued to have success inside the Kingdom, rolling up al-Qaeda cells, arresting individual supporters and uncovering large caches of weapons. But in Yemen, AQAP had breathed new life into jihad. When AQAP leader Abu Basir Nasir al-Wuhayshi (referred to in AQAP publications as Amir Abu Basir) announced the merger, he made it clear that AQAP would target the government of Yemen as well as Saudi Arabia and America. Al-Qaeda no.2 Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri confirmed that al-Qaeda’s central organization considers al-Wuhayshi the amir of AQAP and endorsed the merger (al-Jazeera TV, December 22, 2009).

Yemen has always been a high priority in al-Qaeda’s global strategy. The strategist Abu Mus’ab al-Suri tried to convince Bin Laden to move al-Qaeda’s central organization to Yemen as early as 1989. Although Bin Laden had long-term strategic plans for Yemen, his ancestral homeland, he thought that al-Suri’s plan would be too difficult to carry out at that time because it would require the cooperation of a number of diverse Yemeni Islamist groups. [3] Like other jihadis, al-Suri thought that Yemen, because of its conservative tribal social structure, size, mountainous terrain and strategic location, would be an ideal location for jihad (see Terrorism Focus, February 7, 2008). Although al-Qaeda’s leaders in Yemen have ordered some attacks and condemned the nation’s secular government, it is likely that AQAP’s intention was to stay below the threshold of activity that would incite the government to renew the kind of attacks that nearly destroyed it previously. Clearly, the Houthi rebellion and the secessionist movement in south Yemen are existential threats in a way that al-Qaeda is not. [4] It was natural for AQAP to assume that the traditionally bad relations between Yemen and Saudi Arabia would allow plotting against the Saudis without triggering a strong response from President Saleh. Jihadis in Yemen have traditionally used al-Suri’s writings and tapes (sometimes under the alias Khaled Zayn al-Abidin) about the jihad experience in Syria and Afghanistan as training materials and should be well-schooled in his strategic analysis concerning the use of safe havens and the setting up of resistance fronts.

Deciphering AQAP’s Strategy

With the establishment of AQAP, the tempo of operations has increased and become more dramatic, if not more effective, in both Yemen and Saudi Arabia. What is the organization trying to achieve? From al-Awlaki’s article and the consistent statements by al-Qaeda over the years, we would have assumed that the ultimate goal of AQAP is the establishment of an Islamic emirate throughout the Arabian Peninsula, beginning with the withdrawal of U.S. forces, followed by the overthrow of the Saudi ruling family. Al-Suri had argued that a hierarchal structure mixing secret operations with overt propaganda operations was the source of the destruction of many jihadist organizations in the modern period. Accordingly, we might have expected the relatively modest AQAP organization to encourage clandestine operations inside Saudi Arabia and restrict its operations in Yemen to a steady stream of polemic and only occasional attacks on Yemeni forces. When AQAP stepped forward to claim the attempted Christmas bombing of Flight 253, al-Wuhayshi was deliberately painting a target on himself and AQAP for the United States. He surely would have expected the government of Yemen to bow to American pressure to take strong measures against AQAP. Yet, al-Wuhayshi changed the game and dramatically increased the risk to himself and his organization. [5]

AQAP’s actions only make sense if the group is following the doctrine found in Abu Bakr al-Naji’s Idarat al-Tawahhush (The Administration of Savagery). [6] In al-Naji’s thinking, the Afghan jihad defeated the Soviet Union, not by driving its forces out of Afghanistan, but by drawing them in until they exhausted their ability to fight and the Soviet economy collapsed. Al-Naji’s doctrine, drawn from the Afghan experience, is based on a simple formula: enrage the United States so that it oversteps local security forces and engages directly with local jihadis, which in turn incites other Muslims to join the fight against the “occupying” power, thereby increasing al-Qaeda’s strength and prestige. The strategy assumes that local Muslims will have much greater staying power than the United States because they can fight so much more cheaply and have a greater tolerance for casualties. Another strategist who became prominent after al-Suri’s arrest, Muhammad Khalil al-Hakaymah, has emphasized the importance of jihadists working closely with the local Muslim populations in whose sea they must swim and upon whom they depend for recruitment, protection, and financing. [7] Therefore, al-Qaeda operatives should avoid killing Muslim civilians in general attacks against buildings or market places and should also avoid creating scandals by using brutal methods such as videotaped beheadings. Hakaymah, like al-Suri, argues that individual attacks unconnected to a central organization are the best tactic when the jihadist group is not in a position to take on the local government.

If AQAP’s intention is to start its attempt to create the Islamic Emirate of the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen, the Christmas attack may have been intended to draw U.S forces into Yemen, as al-Naji’s doctrine recommends. When a jihadist organization is facing “occupying forces” the strategy calls for setting up a front in a remote area and fighting the logistically strained Western forces with the full support of the local populace, which is expected to be inflamed by the foreign presence. A statement signed on January 14 by 150 Yemeni clerics that called for jihad if any party invades the country appears to support the notion that AQAP is following al-Naji’s prescription and taking advantage of al-Hakaymah’s recommendations (al-Bawaba, January 14; Asharq al-Awsat, January 14). One cannot help but think that al-Qaeda’s leadership would welcome another American entanglement in addition to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Conclusion

Days prior to the Christmas Day attack, AQAP’s leadership stated that they are fighting America, not the Yemeni military (al-Jazeera TV, December 22, 2009). With President Obama having stated that the United States will not send troops to Yemen, it seems that AQAP will be fighting Yemeni security forces exclusively, albeit with American technical help. President Saleh’s offer to talk to al-Qaeda “if they lay down their weapons and denounce violence” was basically an offer to talk to AQAP if they stop being al-Qaeda, a statement framed to sound reasonable without in any way constraining Yemen’s military forces from attacking AQAP. Unless President Saleh’s forces are extraordinarily successful, however, we should expect al-Qaeda to stage more provocative attacks against U.S. citizens and interests outside Yemen, perhaps using American citizens as foot soldiers. Yemen is not the new Afghanistan. Instead, Yemen, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan are all players in the new phase of al-Qaeda’s adaptive strategy aimed at exhausting U.S patience and resources. At this stage, however, AQAP is still relatively small and vulnerable to local forces.

Notes:

1. In August 2009, AQAP forces attacked Yemeni military forces in Marib. See NEFA Foundation for translation of AQAP communication about this attack. https://www.nefafoundation.org/miscellaneous/AQIY%20battle%20in%20Mareb.pdf.

2. In addition to the failed attack on flight 253, Abdullah Hassan Asiri failed to kill Saudi Prince Muhammad bin Nayef (August 28, 2009 ); Saudi Arabian forces also announced killing two would-be suicide bombers on the border with Yemen (October 13, 2009). For other highlights of the past decade see: https://www.aawsat.com//details.asp?section=4&article=553064&issueno=11372.

3. See Jim Lacey (ed.), A Terrorist’s Call to Global Jihad, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2008, pp 145-54.

4. In January 2010 the chairman of the board of directors of the Yemen News Agency repeated the accusation that Iran is supporting the Houthis and stated that al-Qaeda cannot pose the same level of threat as the northern rebellion. https://www.sabanews.net/en/news203619.htm .

5. An audiotape allegedly recorded by Osama bin Laden appeared to claim responsibility for the attack, though not explicitly. The authenticity of the message has not been confirmed (al-Jazeera, January 25).

6. In January 2010 the chairman of the board of directors of the Yemen News Agency repeated the accusation that Iran is supporting the Houthis and stated that al-Qaeda cannot pose the same level of threat as the northern rebellion. https://www.sabanews.net/en/news203619.htm .

7. A translation of this work in full may be found at https://www.tawhed.net/c.php?i=21 .

8. See Jim Lacey (ed.), The Canons of Jihad, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2008, pp.147-161.