Chechnya’s Kadyrov Wants to Revive Tsarist-Era ‘Savage Division’

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 15 Issue: 68

By:

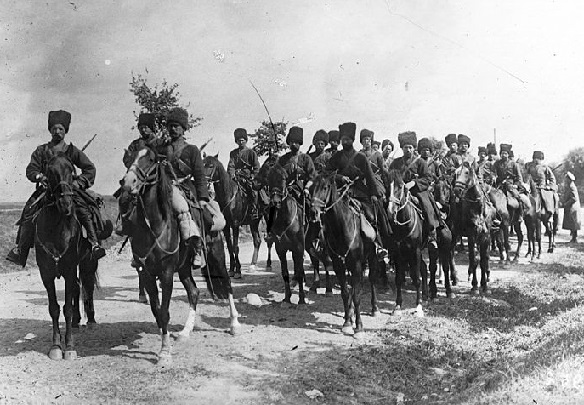

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov wants Moscow to allow regional leaders to organize non-Russian military formations on the model of one of the most legendary units of the Tsarist army in World War I, the so-called “Savage Division” (Dikaya Diviziya), which consisted of regiments largely but not exclusively from predominantly Muslim regions in the North Caucasus (Trud.ru, April 24). Officially called the Caucasian Native Cavalry Division, it gained fame for its soldiers’ bold—some would say “foolhardy”—bravery that spread terror among German and Austro-Hungarian forces (Vestnik Kavkaza, November 20, 2014).

Kadyrov’s proposal, made during an interview with Vesti-24 TV in late April, is not completely new. Eight years ago, many in Moscow were talking about it as a possible solution to the demographic challenges the Russian military faces in attracting sufficient numbers of draftees while avoiding having too many Muslims in largely ethnic-Russian units (The Moscow Times), October 19, 2010). And this time, the idea may enjoy an even wider hearing for several reasons: First, is Kadyrov’s closeness to President Vladimir Putin. Second, the Russian military is dealing with some serious funding problems, as highlighted by a report today that the defense ministry is cutting back on telephone calls to save money (Kommersant, May 3). And third, Putin is clearly interested in using forces like private military companies (see EDM, March 16, 22, 2017; April 19, 23, 2018) or other semi- or unofficial arrangements because any losses within such formations are unlikely to have broader resonance. Indeed, the appearance in the Russian media of a new and upbeat description of the original Savage Division points to that conclusion (Russian7.ru, May 1).

The attractions of this idea are obvious, even if, in most, cases problematic: The creation of such separate ethnic units would reduce the share of non-Russians and especially Muslims in the regular army, thus decreasing the number of conflicts among them. It would give the Kremlin, at least potentially, a janissary-like force it could deploy abroad or against opponents at home at low cost to itself. It could provide an alternative for some young men in the North Caucasus who might otherwise join militants in the mountains. It could allow non-Russians in the North Caucasus more chances to serve in the military than they now have—draft quotas there are still far lower relative to the size of draft-age cohorts than elsewhere (see EDM, April 10). “The military ticket” is need for positions in the police and even the civil service in those republics. And finally, it would give non-Russian leaders like Kadyrov added leverage in their dealings with Moscow. Much of the Chechen leader’s independence is based on the fact that he de facto already has a large armed force under his control (see North Caucasus Weekly, June 15, 2006).

But the dangers of such a course are also clear. Thus, it is certain to worry many in Moscow, generate resistance especially among military commanders and, at the very least, likely to make Vladimir Putin reluctant to agree to this proposal from his Chechen ally. Such a step would violate the longstanding tradition among Soviet and Russian commanders against ethnic units. It would likely undermine command and control in the Russian military by creating ethnic exceptionalism and lead to negotiations about shifting forces about. It would reignite demands for local basing by both Russian and non-Russian troops, limiting Moscow’s flexibility. It would spark nationalism among ethnic Russians, who would thus be encouraged to view themselves as first-class citizens, and among non-Russians, who would see such units (which almost certainly would not be given the most up-to-date weaponry) as a sign of their second-class status. And most seriously of all, such units would give republic leaders resources they might use to pursue independence from Moscow under certain conditions.

But because the issue is clearly being discussed behind the scenes in Moscow, it may be useful for observers in the West to know more about the Savage Division. Officially called the Caucasian Native Cavalry Division, it was formed by the Tsarist authorities in 1914 and consisted of regiments from across the North Caucasus. Its supreme commander was Grand Duke Mikhail Aleksandrovich, but its officers consisted both of local co-ethnics and some Russians. It gained fame for its lighting attacks, especially on the Austro-Hungarian front. Its nominal strength was 3,450 officers and men, but between 1914 and 1918, more than 10,000 soldiers passed through its ranks, an indication of the enormous losses it sustained. As the war ran on, the Savage Division remained loyal first to the Tsarist regime and then to the Provisional Government, abandoning that position only at the time of the Kornilov Affair, when agitators from the Caucasus encouraged these North Caucasus units to return home and fight for the independence of their homelands.

During the Russian Civil War, units of the Savage Division fought alongside General Anton Denikin’s White Army in the south; but the Russian nationalist attitudes of Denikin’s command led some in the Savage Division to pursue their own agenda—in particular, in supporting autonomy or even independence for the North Caucasus. Nonetheless, the commitment of the soldiers of these units to the lawful governments in Russia won them plaudits in the Russian emigration, as exemplified by the best-selling 1928 émigré novel The Savage Division, by Nikolay Breshko-Breshkovsky, which appeared not only in Russian but in French and other languages.

Whether the Russian political leadership is truly weighing the possibility of recreating ethnic units within the Armed Forces remains to be seen. And Kadyrov’s remarks to that effect may have been a predetermined trial balloon. But for now, a lack of clarity about the Kremlin’s position endures.