China Overhauls Diplomacy to Consolidate Regional Leadership, Outline Strategy for Superpower Ascent

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 24

By:

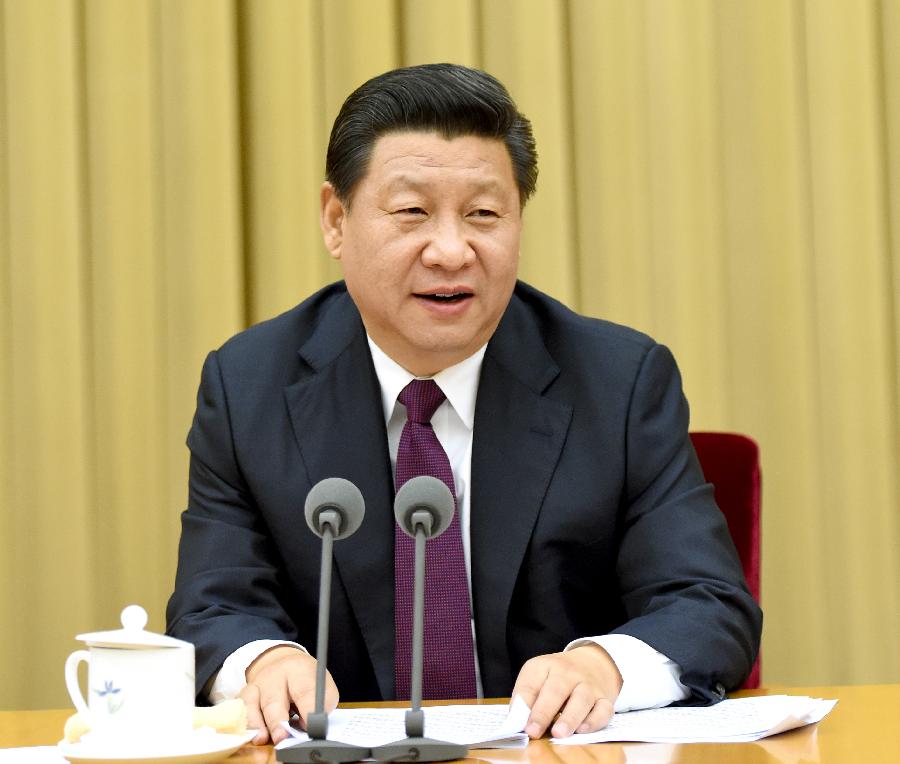

At the Central Work Conference on Foreign Relations held on November 29, China’s leaders outlined the most sweeping changes in decades to longstanding guidance on foreign policy. Chinese President Xi Jinping outlined instructions to consolidate China’s leadership of Asia and strengthen international support for Chinese power. While Xi’s direction to increase the country’s contributions to address global problems offers the welcome prospect of cooperation with the United States on pressing problems, the conference’s outcomes also point to an increasing competition for leadership and influence at the regional and global level. With its options for constraining Beijing’s power receding, Washington will find itself under pressure to step up competitive and cooperative policies to protect U.S. interests in a manner that avoids escalating tensions to the point of a destabilizing rivalry.

According to Xinhua, the purpose of the Central Work Conference on Foreign Relations centered on designating the “strategic objectives and principal tasks of foreign affairs work.” President Xi explained that the main goals were to defend China’s core interests, shape a favorable international environment and create opportunities to enable the nation’s ascent to great power status. Xi linked these efforts to the realization of the “two centenary goals” of realizing the “China Dream” and national rejuvenation (Xinhua, November 29).

China last held a Central Work Conference on Foreign Relations on August 21–23, 2006. At that event, then-President Hu Jintao presented a more restrained ambition that sought to ensure a stable international environment to enable the country’s development. Hu presented a vision of the global order, called the “harmonious world,” but gave little specific guidance on how to achieve it. He also proposed an early version of the core interest idea, when he called on the nation’s foreign affairs workers to “realize, safeguard, and develop the fundamental interests of the broadest majority of the people” (Xinhua, August 23, 2006).

Growth in National Power Drives Revision of Policy Agenda

The change in policy approach owes to the fact that China has seen a significant increase in its national strength in past years, especially relative to other competing great powers following the global financial crisis of 2008. Europe’s economy has stagnated and the very survival of the European Union appears increasingly open to question. Despite a promising start under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Japan’s economy continues to sputter. Russia’s provocative moves regarding the Crimea obscure gloomy prospects for the ailing petro-state. The United States has seen a healthier recovery, but growth has been uneven and the country remains riven by political division. China, meanwhile, dramatically ratcheted up investment to sustain high growth rates. By 2010, its economy had surpassed that of Japan to become the second largest in the world. China’s economy faces slower growth in coming years, and the country suffers its own considerable array of domestic pressures and economic vulnerabilities. However, even at slower growth rates, the gap between China’s national power and that of the United States will continue to narrow.

Not only is China poised to potentially become the largest economy in the world in the coming decades, but the developing world as a whole will likely see large gains. Developing countries are likely to see their share of global GDP rise from one quarter in 2011 to nearly one half by 2025 (World Bank, 2011). Moreover, much of the growth in the future is expected to occur in Asia. These are the trends hinted at by President Xi when he commented that the trends towards “multi-polarity” and economic globalization “will not change.” The growing strength of the developing world and projected flat growth trajectory of the developed world carries huge implications for the future of global politics. Chinese leaders grasp this potential keenly. Xi proclaimed at the conference that the “trends toward the transformation of the international system will not change.”

Directives issued at the conference seek to take advantage of these trends by upgrading the country’s diplomatic power to a level commensurate with its economic and military strength. At the conference, Xi called for China to carry out “diplomacy as a great power” (daguo waijiao). Foreign Minister Wang Yi has explained that China must “conduct great power diplomacy, cultivate a great power mentality, foster great power sentiments and demonstrate great power bearing” especially when “dealing with small and medium sized nations.” (People’s Daily, November 22, 2013).

Among the important instructions issued at the conference, China’s leaders have elevated the pursuit of leadership in Asia as a priority above relations with the United States. China’s leaders have also directed greater efforts to assume greater global responsibilities, bolster China’s leadership of the developing world and increase the appeal and competitiveness of its moral and political values worldwide.

Consolidate Regional Leadership

Among the changes in policy direction, the elevation of relations with the periphery in priority stands among the most significant. The change is a recent one and descends most from Beijing’s pursuit of structural reforms, both domestic and international, to enable the country’s continued development and rejuvenation (see China Brief, June 19). Although Chinese academics have debated the relative importance of China’s ties with the periphery over those with the United States since at least 2011, only in 2013 did Chinese officials begin to refer to the periphery as the “priority direction” (youxian fangxiang) for foreign policy (Global Times, January 2, 2011). The Central Work Forum on Diplomacy to the Periphery in October 2013 demonstrated that a major change was afoot (see China Brief, November 7, 2013). The recently concluded conference confirmed this new policy direction.

Since at least the start of the reform and opening up period, Chinese leaders have consistently prioritized stable, productive relations with the developed world. Western countries like the United States, Japan and countries in Europe have long offered the technological know-how and wealthy markets that China desperately needed to power its growth. The industrialized powers also had the overwhelming military superiority and global political influence that posed the greatest threat to the rise of a weak and vulnerable China.

Trends decades in the making have eroded considerably the importance of the industrialized world to China. The global financial crisis has left much of the developed world reeling in economic and political stagnation. Technologically, China has narrowed considerably the gap in knowledge and capability with the developed world, although its ability to innovate remains weak. Emerging markets appear poised to possibly outpace the developed world as engines of demand and growth. And a still rapidly modernizing PLA continues to narrow the gap in capability with modern militaries, especially in China’s surrounding waters.

Economic and strategic drivers, meanwhile, have elevated the importance of China’s relationship with the region. Successful integration of the economies of China and its neighbors appears increasingly essential to realizing the long-term potential of Asia and strengthening China’s ability to influence the international order. Days after the conference, the Politburo held a study session on the development of a regional Free Trade Agreement. At that event, Xi explained that China needed to make free trade agreements to play an “even bigger role” in trade and investment. He added that China should “participate and lead, make China’s voice heard, and inject more Chinese elements into international rules” (Xinhua, December 6).

Moreover, China realizes it must secure its geostrategic flanks to prepare the country’s ascent into the upper echelons of global power. Chinese leaders are deeply aware of historical precedents in which aspirants to regional dominance in Asia and Europe fell victim to wars kicked off by clashes involving neighboring powers. The persistence of disputes and flashpoints in the East and South China Seas makes this danger vividly real for Chinese policy makers. Finding ways to consolidate China’s influence and weaken potential threats, such as the U.S. alliance system, offers China hope of greater security (The Diplomat, June 11). In the words of Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin, the “imbalance between Asia’s political security and economic development has become an increasingly prominent issue” (People’s Daily, November 27).

According to Liu, Asia can make steady progress only when it builds an “ever closer community of shared destiny” (People’s Daily, November 27). Xi also called for building a “community of shared destiny” at the just-concluded work conference. The “community of shared destiny” (mingyun gongtong) provides the vision for realizing Asia’s economic potential and achieving a more durable security for Asia. As defined by Chinese leaders, the community of destiny is based on deep economic integration, but it goes beyond trade. It is a vision of a political and security community in which economically integrated countries in the region support and defend one another from outside threats and intruders, as well as manage internal threats together through collaborative and cooperative mechanisms. Premier Li Keqiang hinted at this meaning when he explained regional integration means “two wheels of political and security fields should move forward at the same time” (Xinhua, November 13).

Vice Foreign Minister Liu has provided an even more detailed explanation. He stated that a “community of shared destiny” requires countries to:

- Build a “community of shared interests.” Countries should focus on converting their “economic complementarity” into “mutual support for development.” The extensive regional economic and infrastructure integration provides the “material foundation” for the community;

- Build a “community of shared responsibility.” He explained that this meant “countries in the region” should hold “primary responsibility” for “safeguarding regional security.” It also required countries in the region to “work together to defend regional peace and stability.” This idea echoes Xi Jinping’s declaration that “Asians have the capacity to manage security in Asia by themselves” (Xinhua, May 21);

- Build a “community of people and culture.” Different civilizations in Asia should “strengthen exchanges” and “be inclusive toward and learn from each other.” This principle envisions the strengthening of a regional, Asian identity and greater respect for China’s culture and values (People’s Daily, November 27).

Through policies such as the promotion of free trade agreements, infrastructure investment and development of consultative security mechanisms, Beijing hopes to render the fates of a growing number of rising and prosperous nations in Asia dependent on China’s fate as a great power—and marginalize the United States in Asia’s future (see China Brief, July 13).

In Search of an International Constituency

Beyond the region, China is looking to build an international base of support, primarily in the developing world, to back the exercise of Chinese power. President Xi declared at the conference, China should “make friends and form partnership networks throughout the world” and “strive to gain more understanding and support from countries all over the world” for the Chinese dream. Xi emphasized in particular the importance of what he called “major developing powers” (kuangda fazhanzhong guojia), a recent entry into the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) lexicon of policy guidance, for which Xi outlined instructions to “expand cooperation.” [1] He also called on China to “strengthen unity and cooperation” with other developing countries and reaffirmed directions to “closely integrate our country’s development” with that of “major developing countries.” China seeks closer partnerships with countries to support its vision of partial accommodation and partial revision of the global order, as well as more smoothly enable the country’s development and security.

A 2013 article in the Party journal Outlook outlined criteria to prioritize and evaluate relations with countries based on their strategic importance and potential receptivity to Chinese economic ties and political influence. The article highlighted in particular countries along China’s periphery, as well as states in geostrategic locations such as the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. It also singled out as important emerging great powers such as Russia, Brazil and South Africa. The article argued that these are the partners needed to “jointly push the reform of the international system” (Outlook, March 7, 2013). Another academic explained the leadership’s focus on cultivating international support, noting, “if China were to fight on its own, it would be at a considerable disadvantage in terms of strength and influence” (Xianqu Daobao, May 30).

Assuming Greater Responsibility as an International Power

Xi’s direction for the country to take on more global responsibilities provided another important development at the conference. China seems especially committed to finding new ways to contribute in developing countries, where countries are most in need, where China’s overseas interests are often highly vulnerable and where Beijing sees the most potential for partners to support its reform of the international order.

Chinese analysts recognize that China currently suffers a weak reputation as a world leader. One expert observed that the best way for China to build its “international reputation” is by “taking on more responsibilities in international security” which means “providing the entire world and all regions with more public security goods” (Xianqu Daobao, May 30).

Chinese leaders define the country’s provision of “public goods” to the international community differently than the United States. Wang Yi explained that China intends to set itself up as the “defender of the cause of world peace” and to “safeguard the goals and principles of the UN Charter, and oppose foreign interference in the internal affairs of other countries, especially small and medium countries.” It also means China intends to be a “vigorous promoter of international development,” and to contribute to UN goals related to development and poverty relief, climate change, and other global issues. An example of China’s new approach to a more active policy might be seen in South Sudan, where Beijing sent a 700-man infantry battalion to support UN peace keeping operations and took a leading role in mediating between warring factions (see China Brief, October 10; Ministry of Defense, September 25; The Diplomat, June 6).

Articulating a Moral, Political Vision for Global Leadership

The desire for stronger international political influence has raised the imperative for Beijing to articulate a compelling vision of political and moral ideals around which China can appeal for support. The significance of the “profit and righteousness” concept (liyi guan), so heavily emphasized by President Xi and other Chinese leaders, lies precisely in the recognition that money is not enough to secure global influence (see China Brief, November 7, 2013). Beijing recognizes that it must articulate a compelling morality and political idealism that it can argue is superior to the one that currently exists. Xi declared at the conference that China should have a “correct viewpoint about justice and benefits, see to it that equal importance is attached to justice and benefits, stress faithfulness, value friendship, carry forward righteousness, and foster ethics.” He urged diplomats to uphold principles of “non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries” and “oppose the use or threat of force at every turn.”

The vision by President Xi at the conference and many other venues aims to appeal to emerging powers that China believes hold similar grievances regarding the current order. Xi stated China should “persist in promoting greater democracy in international relations,” and “insist that all countries, big or small, strong or weak, rich or poor, are equal members of the international community.” Lest there be any doubt as to the purpose of the message, Xi made clear that China should seek to “speak for other developing countries.”

The flip side of Beijing’s relentless promotion of the supposed superiority of its own political values and moral vision has been an equally relentless denigration of the weaknesses and failings of the values and morality of the current, Western-led order. Xi Jinping made news when he praised a virulently anti-U.S. blogger earlier this year, but commentary in official press are routinely filled with harsh denunciations of Western hypocrisy, immorality and abusive policies (New York Times, November 12).

Implementation: Shaping the Behavior of Other Countries

Another major change from the Hu Jintao era has been the Xi administration’s elaboration of mechanisms to implement the foreign policy agenda. Chinese authorities are revamping policies to reward and punish countries as a way to shape their behavior in a direction desirable for Beijing. A commentator article in the state-run People’s Daily stated that China must “resolutely maintain our country’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests, effectively strike back at provocation and acts of violations of rights by a small number of countries” and “wage a resolute struggle against acts that interfere in our country’s internal affairs” (People’s Daily, December 2).

Chinese scholars argue that countries should be evaluated based on how much their relations support or oppose Beijing’s preferences, so as to provide “clear political direction” for specific policies. One prominent scholar explained that countries should be classified according to “friendly,” “cooperative,” “ordinary” and “conflict” based relations. For friendly countries, policies should demonstrate “ benevolence and mutual assistance;” for countries that cooperate with Beijing, a policy of “appropriate concern” is in order; and for nations with ordinary relations, China should show a “policy of equality and mutual benefit”: for countries with more conflict-ridden relations, however, Beijing should show a “tit-for-tat policy” of graduated retribution (Global Times, August 25). This logic resonates with the logic of the “bottom line principle” mentioned by President Xi and other senior officials (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, August 16, 2013). Officials cited this idea when explaining China’s diplomatic punishment of countries such as Norway (over its decision to honor dissident Liu Xiaobo), the United Kingdom (for its treatment of the Dalai Lama), and the Philippines (over the Scarborough Reef dispute) (The Diplomat, May 9; Telegraph, June 12).

Implications for the United States: The Price of Sino-U.S. Cooperation

While elements of the changes to China’s foreign policy program herald good news for cooperation at the global level against common concerns, the risk of an entrenched rivalry is growing. China’s growing parity in comprehensive national power with the United States alone increases the likelihood of an intensifying contest. Moreover, China understandably expects a greater voice in determining the international order as a fair price for its greater contributions. To gain the leverage necessary to ensure change, China seeks to consolidate its leadership of Asia, build a global coalition of sympathetic partner nations, bolster its credibility as a global leader and articulate a compelling political and moral vision it regards as superior to that of the United States.

The world has benefited from the decision by the leaders of the United States and China to build a stable, cooperative relationship, hailed by China as a “new type great power relationship.” But the benefit China gains from stable cooperation with the United States must be measured against the costs, and for Beijing the benefits appear to be diminishing rapidly. Moreover, the price of cooperation to U.S. interests is mounting as well: Stable U.S.-China ties have freed Beijing to deploy its considerable resources and tolerate greater short-term instability along its periphery to muscle greater control of disputed territories from its neighbors. Nor is this all. China’s pursuit of a stronger global leadership role suggests an even higher price may await the United States in the form of a more destabilizing, systemic competition should China succeed in consolidating its leadership of Asia.

For these reasons, the United States will likely soon find itself under pressure to increase both competitive and cooperative policies aimed at molding a friction-filled collaborative U.S.-China relationship that protects its interests while avoiding a full-blown rivalry. More effective competition for regional and global leadership offers the prospect of granting the U.S. leverage to shape the terms of cooperation with China. Similarly, enhanced U.S.-China cooperation is increasingly vital to restraining competitive impulses. The approach may seem contradictory, akin to driving a car by stepping on the gas and the brakes at the same time. Yet the halting, lurching movement of the metaphor may well capture the best that can be made of a situation featuring even worse options.

Notes

- Beginning in 2013, Xinhua has carried numerous articles that have identified China, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, India, Mexico and South Africa as “major developing countries.”