China Strengthens Clout in Kazakhstan Amid Russian Weakness

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 70

By:

On March 26–28, Kazakhstan’s Prime Minister Karim Massimov paid a working visit to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), first to discuss bilateral issues in Beijing and then to attend the 2015 Boao Forum for Asia (BFA) conference in the province of Hainan. Founded in 1997, this non-governmental organization is modeled after the famous World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and focuses its efforts on strengthening regional and intercontinental dialogue. This year, the BFA annual conference saw the attendance of 15 foreign leaders, with Massimov having been the single representative of Central Asia and one of only three senior officials from the former Soviet Union. The other two were Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan and Russian Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov (Kazpravda.kz, April 2; Primeminister.kz, March 26; Boaoforum.org, March 20).

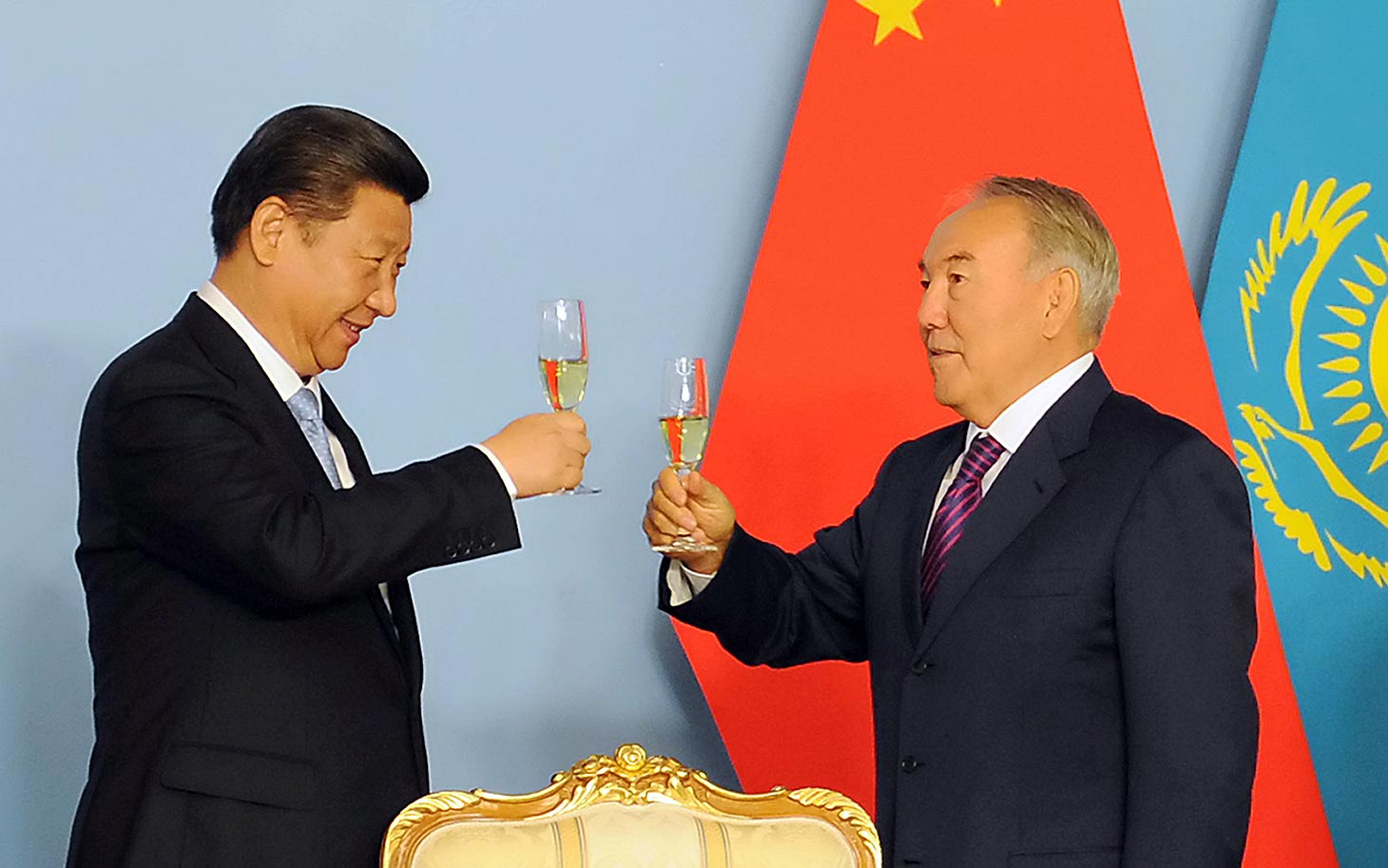

According to media reports, Massimov and his delegation were “warmly welcomed” by Chinese president Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Li Keqiang before proceeding to discuss “all aspects of bilateral cooperation, from cross-border trade to culture and joint scientific projects.” Overall, 33 agreements were signed, amounting to $23.6 billion, in such areas as hydropower generation, crude oil refining, automobile production, metallurgy and civil engineering. Last December, the head of the Chinese government had already visited Kazakhstan, which is invariably presented by Beijing as a key partner in neighboring Central Asia and the whole of the post-Soviet space (Matritca.kz, Lsm.kz, China.org.cn, March 28).

“We sowed the seeds in Kazakhstan in winter, and they are about to bear first fruit,” Chinese Prime Minister Li said last month, thereby referring to the seven agreements worth over $14 billion that had been concluded at the end of 2014, in Astana. Chinese economic diplomacy in Kazakhstan has, until recently, been limited to the oil and gas sector where China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) has gradually expanded its presence, especially after its entry into the giant Kashagan oilfield in September 2013. However, Beijing is now visibly seeking to diversify its local project base, tapping new areas of potential commercial value. Thus, among the contracts signed during Li’s last visit are those that foresee investments into the renovation of Kazakhstan’s power grids, coal conversion into synthetic fuels and the production of nuclear fuel from local uranium ore (Kapital.kz, December 15, 2014; Tengrinews.kz, December 14, 2014).

In mid-2010, Kazakhstan joined with Russia and Belarus to form the Eurasian Customs Union, which applied a common customs tariff to member states’ imports from third countries. This customs union was transformed and expanded into the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) on January 1, 2015. And yet, despite Kazakhstan’s membership in the EEU, the country remains keen to expand trade with China. According to the latest statistical data, last year Kazakhstani-Chinese trade turnover totaled $17.2 billion, of which more than 57 percent were China-bound exports. In contrast, Kazakhstan’s trade with Russia, which stood at $18.9 billion in 2014, is dominated by imports, whose worth traditionally exceeds 65–70 percent of the total bilateral trade ($13.7 billion after $17.9 billion in 2013). Kazakhstan’s trade with Russia plummeted last year by almost 28 percent, mostly due to the global slump in the price of oil and the ruble’s drastic depreciation; and trade with China simultaneously shrank by 20.7 percent. Still, Beijing ranks as Kazakhstan’s second-largest trading partner and, lately, as a leading investor, ahead of Russia (Stat.kz, February 3; Dknews.kz, January 8).

In September 2013, Astana and Beijing inaugurated the Kazakhstan-China Business Council, an intergovernmental forum for economic affairs aimed at enabling the two countries to intensify trade ties on a bilateral basis. The PRC’s earlier attempts to funnel goods and investments into Central Asia through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), of which Russia is also a founding member, had been met with resistance from the Kremlin. The second meeting of the Kazakhstani-Chinese business council last December resulted in the signing of a major financial accord that foresees the opening of a currency swap line up to $1 billion. Earlier, in September 2014, the 9th Kazakhstan-China Subcommittee on Foreign Cooperation had already paved the way for renminbi-tenge swaps on the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange (KASE), followed two months later by a similar move on the interbank forex market of Urumqi, Xinjiang (Newskaz.ru, December 14, 2014; Kase.kz, September 25, 2014; Inform.kz, September 7, 2013).

Meanwhile, Russia has been trying, so far without success, to lure Kazakhstan into a currency union based on the EEU (see EDM, March 27). On March 20, Russian President Vladimir Putin said during a meeting in Astana with his Belarusian and Kazakhstani counterparts—Alyaksandar Lukashenka and Nursultan Nazarbayev, respectively—that the EEU member states (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and, starting in May 2015, Kyrgyzstan) all had conditions in place to establish a common currency. Even if one is not aware of the exact macroeconomic indicators in these countries, current problems in the Eurozone, propped up as it is by the powerful European Central Bank (ECB), should be a lesson for all integration blocs. Inflation alone ranged last year from 3 percent in Armenia to 16.2 percent in Belarus, while total government debt currently amounts to less than 15 percent of GDP in Russia and Kazakhstan but is close to 60 percent in Kyrgyzstan (Vz.ru, March 20).

Unlike Russia, known for its preference for sticks over carrots in relations with its neighbors, China is pursuing a cautious regional strategy. Dubbed the “Silk Road Economic Belt,” Beijing’s approach is, first and foremost, aimed at securing the allegiance of Kazakhstan and other Central Asian regimes through a broad set of economic incentives. Meanwhile, the common currency debate, recently reignited by the Kremlin, is just one of the many examples of Russia’s forceful insistence on unsustainable policies that have an additional disadvantage of further stirring up anti-Russian sentiment.