Beijing Raises Shenzhen’s Status at the Expense of Hong Kong

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 19

By:

Introduction

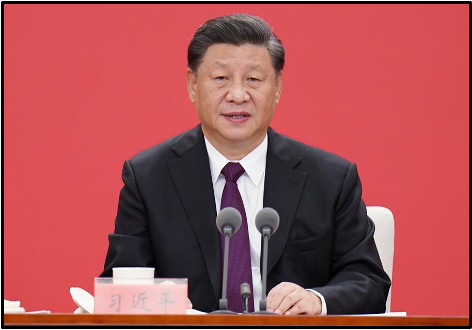

In mid-October, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping unveiled reformist rhetoric by pledging to turn the southern city of Shenzhen (Guangdong Province) into a “comprehensive reform pilot project” (综合改革试点, zonghe gaige shidian), and a “socialism with Chinese characteristics advance demonstration zone” (中国特色社会主义先行示范区, Zhongguo tese shehui zhuyi xianxing shifanqu) for the country’s economic development policies.

Speaking at an October 14 ceremony marking the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ), Xi called upon the city of 13 million to “expand and accelerate all-round opening up policies,” with “institutional guarantees such as rules and norms.” In his address, Xi said that Beijing had allowed Shenzhen to “explore a more flexible policy system and a more scientific management system in terms of domestic and foreign trade, investment and financing, finance and taxation, financial innovation, as well as personnel exit and entry.” Stressing the importance of Shenzhen as a model, Xi vowed that “Reform must never stop and there is no end to opening up [the economy]… Shenzhen must push forward reform and open door policies from an even higher vantage point” (People’s Daily, October 15; Xinhua, October 14).

Xi’s apparent determination to render Shenzhen into China’s foremost showcase for reform stands in stark contrast to his conservative and statist pronouncements that emphasize tight control of the economy by the party apparatus. While Shenzhen has often been touted as “China’s Silicon Valley,” this is the first time that the budding metropolis has been exhorted by supreme leader Xi to excel in the financial sector and services such as accounting, design, and the legal arena. What has brought about this new focus on Shenzhen as a “demonstration zone” for China’s economic development?

New Party Directives for Economic Reforms in Shenzhen

On October 11, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) State Council released the Plan on Implementing Comprehensive Reforms to Build Shenzhen into a Pace-Setting and Pilot Area of Socialism With Chinese Characteristics (2020-2025) [深圳建设中国特色社会主义先行示范区综合改革试点实施方案(2020-2025年), Shenzhen Jianshe Zhongguo Tese Shehui Zhuyi Xianxing Shifanqu Zonghe Gaige Shidian Shishi Fang’an] (hereafter “Plan”). The document listed reforms in 27 areas, intended to make the Shenzhen economy “more marketized, legal-minded and internationalized.” New ways and systems of doing things cover areas including: land use; attraction of both Chinese and foreign capital and talents; expanding the financial and stock markets; and renminbi digitalization. Under the plan, more high-tech firms will be listed on Shenzhen’s Nasdaq-like second bourse. The city has also been designated one of the nation’s foremost “platform[s] for innovation in fintech” (Gov.cn, October 13; Xinhua, October 12).

In his October 14 speech, Xi declared that reforms in the Shenzhen SEZ would open up a “new development scenario whereby domestic and international dual circulations will complement each other” (国内国际双循环相互促进, guonei guoji shuangxunhuan xianghu cujin). In this context, “dual circulation” reiterates a theme unveiled following a Politburo meeting in July—referring to the smooth operation of supply chains, production, logistics, sales, and consumption, in terms of both domestic trade and the world market (China Brief, August 14).

Analysts have noted that while Xi made no reference in his speech to the trade war with the United States—and the possible decoupling of the world’s two biggest economies and supply chains—Xi hoped that the city’s high-tech advancement would help the country minimize U.S.-imposed sanctions on China’s ultra-ambitious “Made in China 2025” program. As Cao Zhongxiong, director of the New Economy Research Centre at the China Development Institute, has indicated, “At this critical moment when international supply chains have blockaded China, how can Shenzhen come up with its own innovation supply chain?” Cao added that this challenge was one of the major tasks for Shenzhen (SCMP, October 14).

Reinforcing Party Leadership Over the Private Sector Economy

At the same time that new reforms are being unveiled, Xi has reminded the bosses of Shenzhen’s predominantly non-state enterprises that they must heed the party’s orders: “We must boost party leadership… Party construction must underpin the entire process of comprehensive reform experiments [in the SEZ].” The practice of setting up CCP cells in private firms—and giving more decision-making powers to party cadres—was the subject of a major CCP Central Committee policy document issued in mid-September (China Brief, September 28).

This tightening of party control over the private sector has also been followed in Shenzhen, a supposed haven of market forces. As veteran Hong Kong-based commentator Johnny Lau has stated, Shenzhen’s development will remain handicapped “if it does not take up reforms in the areas of politics, administration and ideology” (Apple Daily, October 17). Indeed, even though Xi repeated one of the most famous axioms of late patriarch and SEZ founder Deng Xiaoping—”crossing the river while feeling out for the boulders” (摸着石头过河, mozhe shitou guohe)—he stressed in his Shenzhen keynote that Deng-style empiricism must be balanced by dingcengsheji (顶层设计), or design by the top echelon of the CCP. Such top-level design is precisely the guiding spirit of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) that the CCP is currently drafting (Gov.cn, August 7).

Promoting Economic Autarky and the “Greater Bay Area” Concept

Moreover, during his visit to Chaozhou—another Guangdong city noted for its market-oriented economy—Xi underscored the imperative of autarkic, Mao-style “innovation via self-reliance” (自主创新, zizhu chuangxin). “Innovation through self-reliance is an indispensable path for enterprises to boost their core competitiveness and to realize high-quality growth,” Xi indicated. And while the supreme leader also urged senior managers to simultaneously implement “domestic and international dual circulations,” he noted that domestic circulation—meaning relying on the market within China—should be their “main consideration” (Xinhua, October 16; People’s Daily, October 13).

Xi’s speech also carries immense significance for the development of the entire Pearl River Delta, now usually referred to as the “Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area” (粤港澳大湾区, Yue-Gang-Ao Dawanqu), or GBA. Consisting of Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Dongguan, Huizhou, and four other Guangdong cities, the GBA is supposed to spearhead the growth—particularly in high technology, finance, and the service sectors—of all of southern China. Even though Shenzhen’s GDP surpassed Hong Kong two years ago, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR)—which is China’s only international financial center with close business connections with most Western countries—has always been regarded as the dragon head of this region (Hong Kong Economic Times, October 16; Gov.HK, August 27). In his Shenzhen speech, Xi designated the SEZ as an “important engine” for GBA development. In the Plan, Shenzhen was even eulogized as “the core engine” for growth in this experimental region.

Beijing’s Tightening Control Over Hong Kong

As long as Beijing maintains rigid control over capital-account movements and refuses to adopt internationally accepted practices of the rule of law, it is unlikely that Shenzhen can rival Hong Kong as a global financial hub. However, what has particularly alarmed highly-educated citizens of the HKSAR is the bald way in which Xi has advocated the de facto merger of Hong Kong with Shenzhen, Macau, and other GBA cities. After all, the passage of the controversial National Security Legislation last June has subsumed Hong Kong under the mainland’s police-state apparatus (China Brief, July 29).

This was followed by Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s open declaration that there is no “threefold division of power”—including independence of the judiciary—in the HKSAR (RTHK.hk, September 1). In his Shenzhen speech, Xi urged Hong Kong, Macau and the Pearl River Delta to “raise their level of the unification of the marketplace” and in general enhance the compatibility of rules and systems (規則銜接, 機制對接 / guize xianjie, jizhi duijie) throughout the GBA. The Chinese leader went so far as to ask well-educated young people in Hong Kong to build their careers in the GBA.

That the CCP leadership has decided to take a more aggressive stance in shaping Hong Kong’s future is demonstrated by the fact that Chief Executive Lam had originally scheduled to give her annual policy address on the HKSAR’s development on the same day as Xi’s Shenzhen keynote. Now the annual address, which is the most important policy statement of the HKSAR government, has to be postponed until late November. Lam is due to visit Beijing early next month to talk to the heads of various financial and economic ministries. It is understood that she had been told by Beijing to incorporate elements of China’s 14th Five Year Plan into her annual address—and to more closely align the HKSAR’s development with the GBA (HK01.com, October 12; Radio French International, October 12). As Andrew Fung Ho-Keung, head of the Hong Kong Policy Research Institute, has pointed out: “Beijing is becoming more proactive in guiding the governance of the Hong Kong government,” insisting that Hong Kong’s policy address must incorporate elements of the national development game plan (SCMP, October 16).

Conclusion

In mid-September, the CCP passed a new series of CCP Central Committee Work Rules and Regulations (中国共产党中央委员会工作条例, Zhongguo Gongchandang Zhongyang Weiyuanhui Gongzuo Tiaoli). The rules and regulations stipulate that all organizations in the PRC, including the National People’s Congress, the State Council, the military and police, enterprises, and people’s organizations must “self-consciously accept the leadership of the zhongyang [central party authorities].” These units and individuals must also “resolutely uphold the authority of the zhongyang and [its] concentrated and unified leadership, and self-consciously maintain a high degree of unison with the zhongyang in terms of thought, politics, and action” (Ming Pao, October 14; Xinhua, October 12).

Irrespective of the outcome of Xi’s grandiose plans for Shenzhen and the GBA, it is notable that the CCP General Secretary wants to garner support for himself during the Fifth Plenary Session of the CCP Central Committee that opened in Beijing on October 26. Xi regards himself as the personification of the zhongyang, and it seems clear that Xi wants to more emphatically assert his authority as the party’s “core for life.” Xi’s recent and relatively liberal rhetoric, as evidenced by his Shenzhen speech, could be interpreted as an effort to secure the loyalty of party cadres and members who have privately faulted him for being ultra-conservative. These oppositionists include fellow princelings who have criticized Xi for reviving Maoist edicts (Radio French International, September 25; VOA Chinese, September 25). The question remains, however, as to whether giving lip service to market-oriented reforms can help consolidate Xi’s already elevated status as China’s supreme leader.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation and a regular contributor to China Brief. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department, and the Master’s Program in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (2015). His latest book, The Fight for China’s Future, was released by Routledge Publishing in July 2019.