Fair-Weather Friends: The Impact of the Coronavirus on the Strategic Partnership Between Russia and China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 4

By:

Introduction

In June 2019, during a visit to the Kremlin by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Russian Federation announced that they had “agreed…to upgrade their relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era” (Xinhua, June 6, 2019). This continued the warming of bilateral relations nurtured by Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin, who have met at least 30 times during their respective tenures. The strengthening of ties has seen unusually relaxed encounters between the pair, such as when they made blini (traditional Russian pancakes) together in Vladivostok in September 2018 (People’s Daily, September 12, 2018). In more substantive terms, support from Chinese state-linked financial institutions has played a critical role in the construction of a new wave of Russian energy infrastructure, ranging from the Yamal Liquified Natural Gas Project to the “Power of Siberia” gas pipeline.

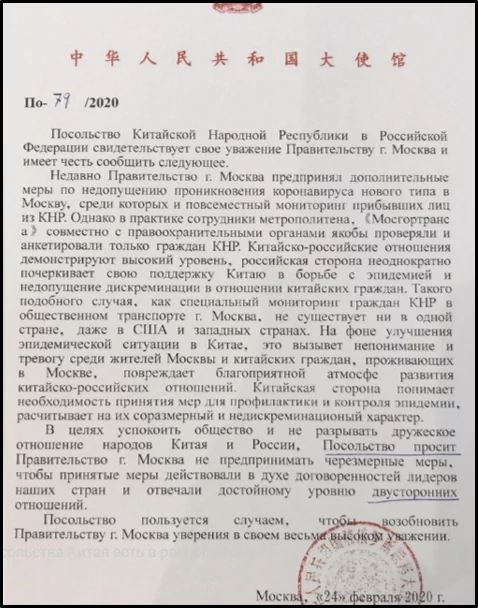

However, the ongoing COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak has opened a stress fracture in the bilateral Sino-Russian relationship. After weeks of gradually escalating restrictions, reports emerged in late February that Moscow public transit drivers had been instructed to call police if they witnessed Chinese passengers using the transit system (Wangyi Keji, February 25). The PRC Embassy in Russia warned that such actions “will harm the good atmosphere for developing Chinese-Russian relations” (Novaya Gazeta, February 25). While China was initially restrained it its public criticism of Russian measures taken in the course of the COVID-19 epidemic, the decision of the PRC Embassy in Moscow to highlight the discrimination being faced by Chinese citizens in Moscow is a reminder of just how quickly tensions can arise between the two countries, even in the age of “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era.”

Russia Raises the Drawbridge

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a “public health emergency of international concern” on January 30, 2020 (WHO, February 27). Two days prior to this, the Khabarovsk regional government had announced the closure of all border crossings connecting Khabarovsk Krai with China (Today KHV, January 28). Following the WHO declaration, the closure was extended across all checkpoints in the Far Eastern Federal District, which covers much of Russia’s border region with China (Moscow Times, January 30). Authorities announced the suspension of e-visa issuances to Chinese nationals, and also prepared an evacuation of Russian nationals from Wuhan. A further evacuation operation took place in Heilongjiang Province, utilizing the newly-constructed bridge between Heihe and Blagoveshchensk, which had been portrayed as a symbol of greater economic integration between the two countries.

While these measures are all grounded in public health logic, other countries that have close political ties with China—and which have benefited substantially from Chinese financing—were much more reluctant in their initial response to COVID-19. Among others, Ethiopian Airlines has continued to operate flights to China throughout the crisis (Xinhua, February 27), while Pakistani authorities have not facilitated the evacuation of its citizens from Wuhan, despite domestic public pressure to do so (DW, February 20). Russia’s response was a reminder that strategic cooperation between Russia and China is highly contingent on overlapping interests.

Trying to Get Along

In the aftermath of the border closure, authorities from both China and Russia appeared to be intent on containing the impact of the crisis on bilateral relations. Chinese state tabloid Global Times said that while the closure is “a bit of an overreaction”, it was “understandable for Moscow to make the hard decision for the health of its own people” (Global Times, February 19). Russian authorities attempted to mollify China by arranging a donation of 23 tons of medical supplies, although there was some consternation that Russia was not among the first 20 countries to do so (South China Morning Post, February 16). On February 4, the Kremlin shared samples of Russian H5N1 drug Triazavirin with Chinese counterparts to assess its effectiveness in treating COVID-19, and also dispatched a team of five experts from the Ministry of Health and the Federal Service for the Oversight of Consumer Protection and Welfare to provide support (Jiemian, February 4). In the background, however, cross-border connectivity continued to worsen: all flights from points of origin in China to airports in Russia other than Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport were cancelled. On February 18, Russian flag carrier Aeroflot announced that it would pare down its China service to just two daily flights, one each to Beijing and Shanghai (Duowei, February 18).

The Economic Impacts Hit Home

On February 20, all Chinese nationals on tourist, private, student, or work visa were blocked from entering Russian territory. In a bid to minimize damage wrought by COVID-19 on economic ties, Russian authorities established a carve-out so that Chinese citizens holding business or official visas would still be permitted to enter (South China Morning Post, February 20). Some companies implemented pragmatic work-arounds, as illustrated by the decision of Gazprom and China National Petroleum Corporation to convene their scheduled meetings via teleconference (TASS, February 13). However, the economic impact has been readily apparent. According to Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov, bilateral trade volume in February 20 was down as much as 50% year-on-year (National Post, February 20)—a considerable setback to previous Russian ambitions for bilateral trade to reach $200 billion by 2024 (Xinhua, September 18). The volume of Alipay and UnionPay payments processed in Russia fell by approximately 70% year-on-year in the first week of February, while one consultancy estimated that in St. Petersburg alone, hotels were facing a revenue shortfall of around $8 million per month (The Art Newspaper, February 26).

A Pre-Existing Condition?

Russia’s border closure is not the first time that one party in the bilateral relationship has placed pragmatic self-interest above economic integration. During his November 2018 visit to Beijing, it was widely expected that then-Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev would, along with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, announce the formation of a joint program to facilitate the payment of cross-border trade in the yuan and ruble, in order to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar (RT, November 23). However, the Chinese side rejected a proposed agreement, due to concern among Chinese banks that any contractual linkages with Russian counterparts would leave the banks vulnerable to accusations of sanction violations. In June 2019, Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development announced that Siluanov and People’s Bank of Governor Yi Gang had signed an intergovernmental agreement under which both sides committed to raising the proportion of cross-border trade settled in national currencies to 50 percent (Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation, June 28, 2019).

However, Chinese government outlets did not release a corresponding announcement. During the Russia Calling Investment Forum in November 2019, Putin conceded that the volume of bilateral trade settled in national currencies remains small. Although he said that he “hopes to see more” trade settlement, he did not make any reference to the June 2019 agreement. The reticence of Chinese negotiators to pursue deeper currency integration is further testament to the importance of overlapping interests in the strategic partnership between Russia and China—in this case, there was a clear mismatch between the need of Russian businesses to minimize exposure to sanctions, and the desire of Chinese banks to maintain access to the international financial system.

Conclusion: The Unsteady Underbelly of Strategic Relations between Russia and China

As recently as September 2019, President Xi described President Putin as his “best friend” (Xinhua, June 6). However, the diplomatic tensions resulting from Russia’s COVID-19 restrictions serve as a reminder that the Sino-Russian bilateral strategic partnership is premised on maintaining overlapping interests. When that overlap diminishes, memories can quickly return to periods of historical enmity. [1] While the current predicament is benign in comparison to historical periods of hostility, the tensions show that a strategic partnership between the two countries does not necessarily rest on a bed of strategic trust. As such, despite the vaguely-defined “comprehensive strategic partnership,” Putin and Xi have refrained from describing the Sino-Russian bilateral relationship as an alliance. Furthermore, PRC state media has also declined to use the term “all-weather friendship” (which it uses to characterize ties with Pakistan) to describe relations with Russia. The restrictions imposed by Russian authorities over the COVID-19 outbreak, culminating in alleged discrimination against Chinese users of Moscow’s public transit system, show that positive leader-level relations have not produced strategic trust between the two countries. Instead, strong bilateral ties are reliant on overlapping interests. While the retort from the Chinese Embassy is unlikely to produce a fundamental shift, it nonetheless offers a warning not to overestimate the ability of Moscow and Beijing to construct an enduring alliance.

Johan van de Ven is a Senior Analyst at RWR Advisory Group, a Washington, D.C.-based consultancy that advises government and private-sector clients on geopolitical risks associated with China and Russia’s international economic activity. He leads RWR’s research and analysis of the Belt and Road Initiative, the centerpiece of foreign policy under Xi Jinping, and also edits the Belt and Road Monitor, RWR’s bi-weekly newsletter.

Notes

[1] Relations between the two countries were hostile from the late 1950s through the 1980s, including armed border clashes and a war scare in the late 1960s. In 1969, the Chinese leadership evacuated its compound at Zhongnanhai, fearing a Soviet nuclear attack. See: Nicholas Khoo, Collateral Damage: Sino-Soviet Rivalry and the Termination of the Sino-Vietnamese Alliance (Columbia Univ. Press, 2011).