Indonesia’s Deradicalization Program Through the Lens of Umar Patek: From Bomb-Maker to Entrepreneur

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 23 Issue: 3

By:

Executive Summary:

- Indonesia has enjoyed some success with deradicalizing high-level militants, including Umar Patek, a key bomb-maker involved with the deadly 2002 Bali bombings. This approach has involved the use of mentorship and entrepreneurial incentives to integrate former Islamists back into society.

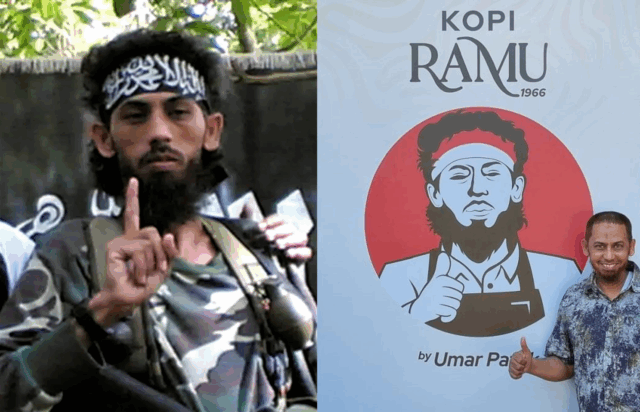

Indonesia’s program to deradicalize former Islamist militants has seen a number of successes in the last several decades. One such example is the continued rehabilitation of Umar Patek (also known as Hisyam bin Ali Zein), the Jemaah Islamiya (JI) bomb-maker who created the devices used in the 2002 Bali bombings to kill more than 200 people (for more, see Terrorism Monitor, March 17, 2023). Patek, who was granted parole on December 7, 2022, is required to participate in an out-of-prison deradicalization program until April 29, 2030. His activities while on parole received particular attention in the Indonesian press when, on June 3, the once-infamous Patek resurfaced somewhat surprisingly as a barista officially opening his own coffee shop (“Kopi Ramu 1966”) in an upscale restaurant in Surabaya, the country’s second-largest city (TUWAGA, June 5; ngopibareng.id, June 1). While the fact that a notorious bomb-maker is launching his own café may be of little importance in and of itself, Patek’s journey exemplifies Indonesia’s approach toward deradicalization, which prioritizes the reconstruction of former jihadists’ social identity by enmeshing them within society and assisting them and their families in achieving economic independence (International Journal of Business, Economics and Social Development [Indonesia], 2021; International Peace Institute, June 2010). Indonesia’s counterterrorism agency, the BNPT (“Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Terorisme” or National Counter Terrorism Agency), has praised Patek’s new coffee shop as a shining example of “successful deradicalization” (Harakatuna.com, June 12; Kolega Kontras Media, June 10).

Initial Failures

Patek previously expressed a desire to open a mini-market with his wife following his release from prison (BANGSAONLINE.COM, August 26, 2021). Patek’s reputation made securing funding for this all but impossible, and his search for employment equally fruitless. Shortly after Patek’s release, however, popular dentist, philanthropist, human rights advocate, and owner of Hedon Estate Kitchen & Lounge—the aforementioned upscale restaurant hosting Kopi Ramu 1966—Drg. David Andreasmito requested a meeting with him. During their first meeting two months after Patek’s release, Andreasmito recognized that Patek, who was making a living as a guest speaker at forums on deradicalization and radicalization, needed a stable job to support his family. Notably, Andreasmito is a Christian, though he follows the pluralistic teachings of former Indonesian president Gus Dur. The idea of Patek opening a coffee shop stemmed from Andreasmito’s first visit to Patek’s home, where he was quite taken by the flavor of a cup of rempah (herbal) coffee said to have been prepared using Patek’s family’s recipe (Kompas Media Nusantara, June 4; TIMES Indonesia, June 6). This prompted Andreasmito to offer to assist Patek in selling his family recipe in Andreasmito’s restaurant, though Patek initially declined out of fear that having his name associated with the effort would ensure the enterprise’s failure (detikcom, Oct 16, 2024; kumparanNEWS, June 5). Still, the BNPT’s deradicalization program promoted the idea of Andreasmito serving as a mentor to Patek, and Andreasmito invited the former bomb-maker to work at his restaurant as a barista to learn the skills necessary to open his own coffee shop.

Mentorship

The BNPT’s mentorship program paired Patek with Ali Fauzi, who finished a PhD in Islamic Studies three months after the former was released from prison. Fauzi himself had been in prison from 2006–2009 on terrorism charges, and several of his brothers were executed for participating in the 2002 Bali bombings (see Militant Leadership Monitor, April 6, 2023). Fauzi personally vouched for Patek, assuring the BNPT’s leadership that he had transformed as an individual and was ready for parole (see Terrorism Monitor, March 17, 2023). It is believed that Fauzi’s influence helped push Patek to accept Andreasmito’s offer. Following this, Andreasmito became Patek’s entrepreneurial mentor in the BNPT’s program, offering him training and supplying the machines necessary to open his shop within the upscale restaurant (KOMPAS.com, June 4). Andreasmito also intervened on Patek’s behalf when an expert coffee roaster brought in to train Patek expressed a reluctance to teach the former terrorist (DISWAY.ID, June 5).

BNPT Oversight

Throughout this period, Patek participated in other parts of the BNPT’s deradicalization programs, where perpetrators and victims of terrorist attacks interact. For instance, on the anniversary of the 2003 JW Marriott bombing that killed 12 and injured 150, Patek expressed his remorse for the attack to the surviving victims (WARTAKOTAlive.com, August 5, 2023). Furthermore, the BNPT continually monitored Patek during his time training as a barista, and continued to follow up after the October 2024 soft opening of Kopi Ramu 1966. The name is intended to signify the reversal of Patek’s course in life, with “Ramu” being the inverse of his first name (kopi means coffee, and Patek was born in 1966). Marthinus Hukom, the former chief of Indonesia’s elite counterterrorism force, Special Detachment 88 (Densus 88), was also present at the soft launch. Hukom was a key player in the capture of Patek and subsequently supported him during his parole (detikcom, Oct 16, 2024; merdeka.com, December 24, 2024; see Terrorism Monitor, March 17, 2023). Hukom returned to Hedon Estate for the full launch of Patek’s coffee shop, expressing during the opening ceremony his hopes that the Kopi Ramu brand could drive the growth of other small businesses in East Java (KOMPAS.com, June 4; tirto.id, June 5). The event also afforded Patek an opportunity to once again express his remorse for the victims of the Bali bombing who came to attend—a far cry from the terse “sorry” elicited from him during his trial, after survivors of the tragedy had recounted their trauma. One survivor even stated that where she once despised Patek for what he had done, she had come to seem him as a new man and forgiven him; she further expressed her hope for the success of his coffee shop, suggesting that she would be happy if it might one day employ members of her own family (SURYA.co.id, June 4).

Conclusion

Patek’s case illustrates how the BNPT’s “humanistic” approach through entrepreneurial partnership and mentorship with former terrorists can lead to meaningful social and economic integration. One significant aspect of Patek’s rehabilitation was the fact that he was willing to engage with Andreasmito, despite Patek’s former Islamist ideology clearly labeling him as a kafir (infidel) due to Andreasmito’s Christian faith (DISWAY.ID, June 5). In an homage to a lesson he had learned from Ali Fauzi, Patek replicated his mentor’s motto on the packaging of his coffee: “Everyone has the right to become a better person” (KOMPAS.ID, June 4; see Militant Leadership Monitor, April 6, 2023).

While Patek’s case represents the best of the Indonesian deradicalization regime, the model is not easily exported to other countries. The individual-focused program can be resource-intensive, is easier to carry out in Muslim states with stronger secular and/or pluralistic traditions, and tends to function best where the active insurgency has been significantly degraded for some time. Similar successes can be seen in the Philippines’ deradicalization efforts, which broadly follow a similar model (see Terrorism Monitor, April 5, 2024). Unfortunately, this also suggests that attempts to use the same approach to deradicalize Islamists in the Middle East or Africa are unlikely to succeed, at least if one were to attempt to implement them today.