Kashmir Jihadism and the Threat to India

Kashmir Jihadism and the Threat to India

It is increasingly evident that each time the relations between India and Pakistan improve, India-focused jihadist groups from across the Pakistani border attempt to disrupt it with attacks in the Indian states of Kashmir, Punjab, and elsewhere. The inevitable aim of these is to upset the possibility of amicable dialogue between these two populous and nuclear-armed nations.

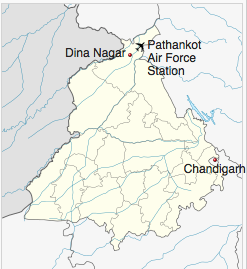

The latest example of this occurred in January when the high-profile Pathankot Air base in the Indian state of Punjab was attacked by militants. The United Jihad council (UJC, also known as Muttahida Jihad Council), based in Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-administered Kashmir (PAK), claimed responsibility for the incident. The attacks and ensuing gun battle at the strategically crucial Indian airbase went on for three days and killed 13 people, including seven Indian security personnel and six militants. UJC Spokesperson Syed Sadaqat Hussain has since threatened similar attacks elsewhere in the country while chiding the Indian establishment for its alleged Pakistan-phobia (Dawn [Karachi], January 4). Days later, the chief of UJC, Syed Salahuddin, also supreme leader of Hizbul Mujahideen, criticized the Pakistani government in a similar vein for its alleged stand in support of India, saying that “Pakistan is not just an advocate, but also a party to the longstanding Kashmir conflict” and that it “should play the role of a patron [to groups like UJC] rather than of an adversary” (Express Tribune, January 20). Salahudin’s comments were issued alongside the Pakistani government’s crackdown on the leaders and infrastructures of another constituent of UJC, Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), as the group’s militants were suspected of being involved in the Pathankot attack.

Rejecting the claim by the UJC as a ploy to divert attention and to confuse their investigation, Indian security agencies investigating the attack have tracked at least four Pakistan-based militant operatives as the prime architects of January’s Patahnkot attack. All are affiliated with Pakistan-based Jaish-e Muhammed, including its chief, Maulana Masood Azhar, his brother Abdul Rauf Asghar, as well as Ashfaq Ahmed, Haji Abdul Shaqur, and Kashim Jaan. While Azhar allegedly oversaw the operations, his brother Asghar and two others were in touch with the militants once they made their way inside the airbase. India shared with Pakistan, the telephone numbers and the identity of the suspected Jaish handlers, among other evidence. Initially, the Pakistani government was said to have acted on information provided by Indian agencies by detaining at least 12 JeM operatives for their alleged involvement in the Pathankot terror attack and sealing branch offices of the JeM located in Bahwalnagar, Bahawalpur, Multan, and Muzafargarh (Daily Pakistan, January 13). It also claimed to have taken Masood Azhar into protective custody (Dawn, January 15). On the ground, however, JeM leadership denied any such detentions or arrests. Moreover, over a month after the incident, Pakistan’s Special Investigation Team (SIT) concluded that there was no substantive evidence to suggest that Masood Azhar or JeM were responsible for the deadly assault (Express Tribune, February 8). In order to secure the safe release of JeM’s supreme leader Masood Azhar from an Indian prison, his fellow militants had previously orchestrated the hijacking of Indian Airlines flight IC 814 in late December 1999, the December 2001 Indian parliament attacks, and a number of coordinated attacks in Jammu, Kashmir, and elsewhere in India.

Most UJC militants, who are either camouflaged under new group names or operating under newly-floated hybrid strike units (e.g. as Al-Shuhada Brigade, Shaheed Afzal Guru Squad and Highway Squad), are largely part of the exiting jihadist groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM). These groups often operate collectively. This tactics help anti-India agencies in Pakistan to keep the vexed Kashmir conflict live and relevant, drawing international attention to the contested nature of the territory, and towards the so-called popular insurgency, while also maintaining a level of deniability.

The Pathankot events were not isolated developments as far as Pakistan-based militants are concerned, but were rather a part of a well-orchestrated militant surge. For instance, one report by the Indian Intelligence Bureau (IB) in April of 2015 warned that six Pakistan based militant groups, including HM, LeT, and JeM, were preparing to launch attacks on security installations in India (India Today, April 1, 2015).

These militant groups have both collectively and independently been attempting to reinvigorate terror infrastructures in Kashmir and beyond, apparently with the patronage of Pakistan’s political, military, and intelligence agencies. There have been many instances of similar violent and well-coordinated strikes in Kashmir and Punjab in the last few years, all emanating from Pakistani soil. Almost after a decade of relative calm in the region, the December 5, 2014 serial attacks in Kashmir and Srinagar killed 21 people, including 11 security personnel and two civilians, in three separate incidents. The fatalities also included eight Pakistani militants who carried out multiple strikes, including an attack at the Indian Army’s 31 Field Regiment Ordinance Camp at Mohra, Baramulla district (Reuters, December 2014).

The latest Pathankot events are reminiscent of July 2015’s Dinanagar (Punjab) attacks where Pakistani militants launched multiple assaults, including an attack on a police station that killed at least seven, including a senior police official. The militants were equipped with sophisticated arms and ammunitions, including a U.S. Night Vision Device (NVD) and Global Positioning Systems (GPS). The U.S. has confirmed that the NVD used in the attack was in use in Afghanistan in 2010 and was lost during battle (IBN Live, September 16, 2015). Exactly how it reached the militants who were slain in Gurudaspur remains a mystery.

The involvement of Pakistan Army’s Border Action Team (BAT) and heavily armed militants in attacks in India has been confirmed on many occasions in the past as a part of a persistent and deliberate attempt by sections of Pakistan’s army, intelligence agencies, and alleged non-state actors sponsored by the state to underline the peaceful atmosphere in neighboring Indian states (The Economic Times, January 20, 2015; First Post, August 18, 2013; DNA India, May 19, 2014). Context for the latest increase in attacks is these groups’ desire to revive anti-India militancy in the India’s Kashmir region, which has seen a decline in pro-separate militancy in the past few years.

The Pathankot attacks and the resulting clamor in India for immediate action against the perpetrators has brought about a significant development. In Pakistan, for the first time, the National Assembly Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs issued a four-page policy paper on Kashmir, suggesting that “Pakistan should not encourage calls for active support to armed, banned, militant groups in Kashmir” (The Express Tribune, February 1). At the same time, however, it should be noted that in recent decades, Pakistan’s Kashmir policy has consistently adhered to few time-tested methods, such as pressing for diplomatic dialogue with India while consistently backing India-focused jihadists in the aim of creating the impression of a broad-based and popular insurgency in Kashmir.

The Pathankot attacks occurred just one week after the December 25, 2015 surprise meeting between Indian and Pakistani prime ministers in Lahore. The attacks led to the cancellation of scheduled follow-up talks between respective foreign secretaries and cooled the warming diplomatic relations between the two countries (The Hindu, January 15). The events therefore illustrate both patronage of militant groups by elements of the Pakistani security establishment opposed to improved relations with India, and also underline the resulting resilience of Pakistan’s Kashmir-centric jihadi infrastructure, which continues to pose a threat to Indian national security.

Animesh Roul is the Executive Director of Research at the New Delhi-based Society for the Study of Peace and Conflict (SSPC).