Kazakh Nationalists Call for Astana to Absorb Orenburg, Outraging Moscow

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 14

By:

Executive Summary:

- Both Bashkir and Kazakh nationalists are pressing for greater control over or outright annexation of Russia’s Orenburg Oblast.

- Russian commentators are calling on Moscow to increase pressure on Astana and expand the Russian military presence in Orenburg to prevent such actions.

- Opening the Orenburg Corridor to connect Kazakhstan with the Turkic peoples of the Middle Volga is a top priority for the Bashkirs and Kazakhs and inattention to this development could lead to future crises and possible armed clashes.

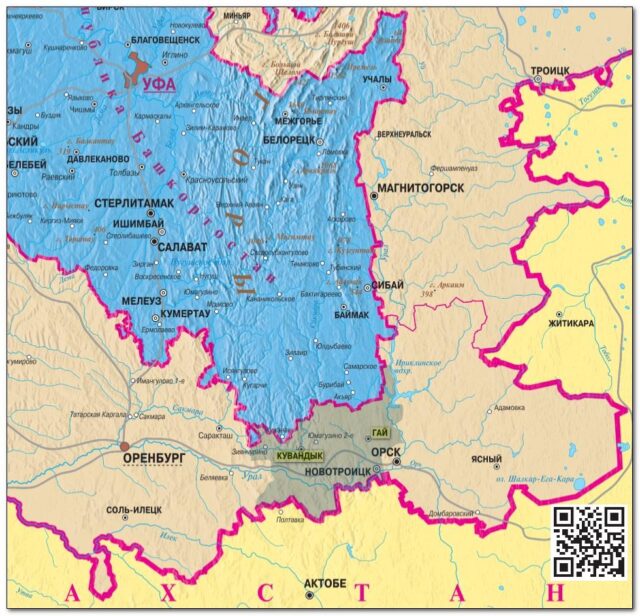

Kazakh nationalists have begun to call for Astana to follow Kyiv’s lead and annex Russia’s Orenburg Oblast. Protests in Bashkortostan earlier this month and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s call for Kyiv to increase attention to ethnic Ukrainian areas in the Russian Federation give fresh impetus to these notions (Idel Real, January 23; see EDM, January 23, 25). Orenburg Oblast lies between Kazakhstan and Bashkortostan. If Astana were to annex the region, it could serve as a bridge between Kazakhstan and the Turkic Muslim peoples of the Middle Volga, as there is currently a Russian wall between them (Abai.kz, January 24). Unsurprisingly, these Kazakh appeals are generating outrage and concern in Moscow, which views them as part of a broader US-Ukrainian strategy to weaken and ultimately dismember the Russian Federation. Some Russian analysts suspect that Kazakhstan’s government shares these views despite its public support for Russia’s territorial integrity. The suggestions that Moscow must increase the Russian military presence in Orenburg to counter this threat demonstrate just how worried the Kremlin has become (Bloknot, January 17; Vzglyad, January 28).

Both the Bashkirs and Kazakhs are interested in Orenburg, and Moscow opposes any changes to the oblast’s status. Similar to the other peoples of the Middle Volga, the Bashkirs in Bashkortostan are surrounded by Russian territory and will continue to be if Orenburg Oblast remains entirely under the Kremlin’s control. The oblast thus has limited chances of pursuing independence. Many Middle Volga residents believe that, if they had shared a border with Kazakhstan in 1991, they would have already gained independence (Milliard Tatar, May 6, 2023). Consequently, the opening of what many call the “Orenburg Corridor” or the “Kuvandyk Corridor,” named for the city through which such a passage would run, has remained a vital aspect of the Bashkir national agenda (Free Idel-Ural, April 28, 2021, June 18, 2023, November 30, 2023). Gaining control over the corridor is so important that some Bashkir activists are prepared to give up other portions of their land to secure it (T.me/astrakhanistan, September 24, 2024). As some Russian and Kazakh commentators have pointed out, such sentiments were evident during the recent protests in Baymak, a Bashkir city near the border with Orenburg (Vzglyad, January 28).

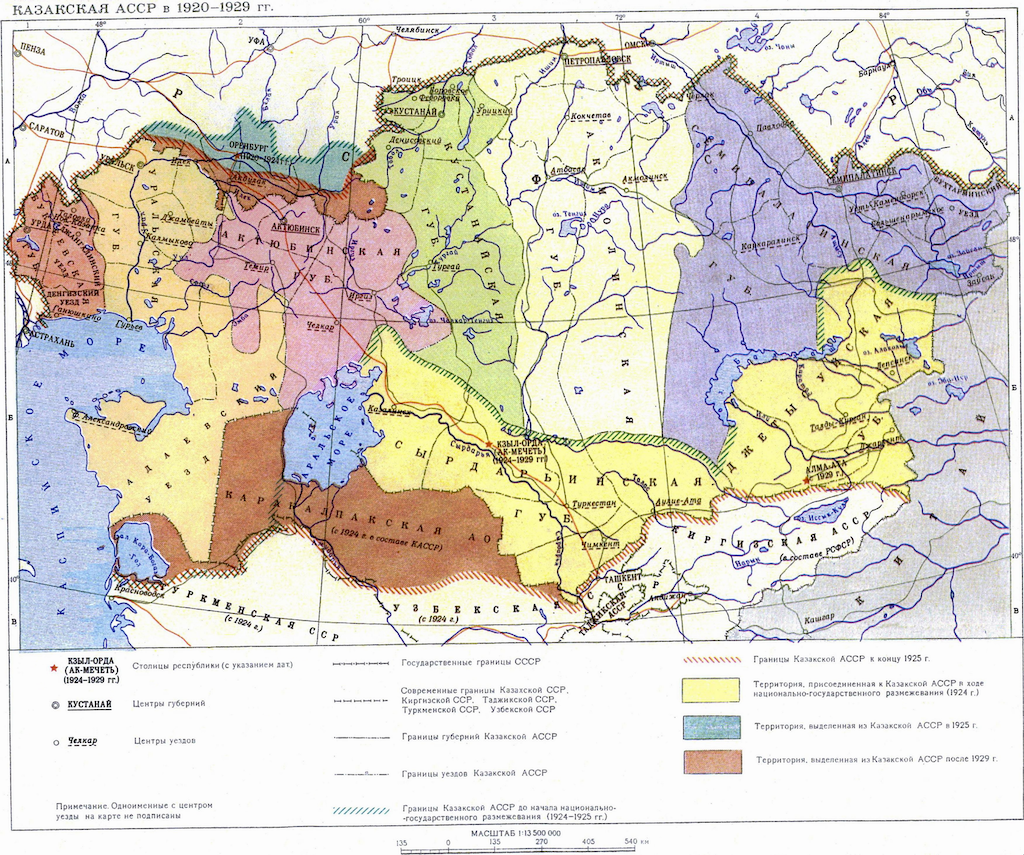

The Kazakhs are interested in Orenburg because, between 1920 and 1925, it was the capital of the Kyrgyz (Kazakh) Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The region remains a symbol of national pride for Kazakhstan. Two other reasons, perhaps even more compelling, are driving this interest. First, Astana aspires to be one of the leaders of the Turkic world. Opening up bridge to the two Turkic peoples of the Middle Volga, the Tatars and Bashkirs, would cement this status. Second, Kazakhstan, just like Ukraine, wants to counter Russian aspirations to absorb part or all of its territory populated by ethnic Russians. Similar to eastern Ukraine, northern Kazakhstan has a predominantly Russian population that some in Moscow have long tried to exploit (see EDM, August 11, 2022; Window on Eurasia, August 27, 2022). Consequently, Astana has an interest in suggesting that any Russian move in that direction would provoke a symmetrical response by its target, an argument Kyiv has long made for itself and others (Kamerton, November 16, 2021; Window on Eurasia, January 5, 2022; Vzglyad, January 28).

Map of Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Source: Wikimedia)

Recent developments have encouraged both the Bashkirs and Kazakhs in their hopes for opening the Orenburg Corridor. On the one hand, demographically, Orenburg’s population, while predominantly ethnic Russian, is declining, becoming less of a Russian bulwark than it once was. The shares of Middle Volga nations and Kazakhs in the population has also shifted. The Tatars and Bashkirs have decreased in number, according to the 2021 Russian census, but the share of Central Asian especially Kazakh nationalities has increased. This pattern helps explain why the Orenburg Corridor is shifting from primarily an issue for the Middle Volga nations to a priority for Kazakhstan. That, in turn, has transformed the issue into a foreign policy challenge for Moscow, not just a domestic consideration (see EDM, November 19, 2013; Window on Eurasia, November 4, 2018). On the other hand, Ukrainian actions and the statements of nationalists in different countries on the need to take or regain control over areas linked to their respective nations have made such claims more acceptable as part of national discourse.

This last development may explain why the Russian population is so wary of Kazakh nationalist statements. Some Russians see discussions on Orenburg as opening the way to talk about annexing other parts of the Russia Federation in Kazakhstan and other countries. They insist that Moscow take defensive measures in these regions and demand that the governments of neighboring countries suppress such talk (Vzglyad, January 26). Many parts of Russia are more closely linked, at least historically, to neighboring countries or non-Russian republics still within the Russian Federation. Kazakhstan itself already features some nationalists who are demanding that Russia’s Astrakhan, which they refer to as Astrakhanistan, be handed over to Astana and serve as a land bridge between Kazakhstan and the Muslim North Caucasus (Vzglyad, January 28). (For more on Astrakhanistan, see T. me/astrakhanistan, accessed on January 30; for more on the Turkic nature of that region, see Window on Eurasia, November 18, 2022, January 28, 2023).

The Kazakhstan government is unlikely to suppress the Kazakh nationalists discussing these two corridors. Astana may issue statements similar to Zelenskyy’s recent pronouncement (see EDM, January 25). Official statements alone, however, are unlikely to discourage the nationalists from pressing on. They will likely be able to do so primarily under Moscow and the West’s radar because nationalism of this kind generally does not appear in Russian media, but rather in the languages of the titular nationalities involved. Those attitudes are likely to change if and when the Russian state weakens and threatens to rupture.

Since the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, Russian and Western analysts have focused on three corridors near the borders of the Russian Federation: the Suwalki Gap between Belarus and Kaliningrad, the Focsani Gate along the Romanian border near Ukraine and Moldova, and the Zangezur Corridor between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave. Now, the time has come to focus on additional corridors as they could lead to future crises, beginning with the Orenburg Corridor as the most important object of concern. Unless plans are made now, dealing with these corridor crises later will become incredibly challenging (Window on Eurasia, December 3, 2023).