Lukashenka and the Nuances of Belarusian Nationalism

By:

Executive Summary:

- Belarusian statehood and national identity have experienced several transformations throughout history, influenced by connections to Russia and the West.

- The Belarusian population is divided between two dominant narratives on national identity: the “Westernizing” and Russo-centric perspectives.

- Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka subscribes to the Russo-centric narrative but, at times, he has sought to find common ground with the Westernizers.

- Lukashenka has worked hard to maintain at least some room for geopolitical maneuver in preventing Russia’s total absorption of Belarus and protecting Minsk’s sovereignty.

- The Belarusian president has repeatedly taken a stand against the Kremlin’s desire to annex Belarus and initiated some attempts at rapprochement with the opposition and the West.

- Official Minsk has had to defend the country’s sovereignty not only from Moscow but also from Belarusian activists who were all too eager to unite Belarus with Russia.

- Some observers of Belarusian politics have claimed that Lukashenka is no nationalist due to his autocratic tendencies.

- The criteria for determining whether someone is a Belarusian nationalist—“pro-European + anti-authoritarian + speaking Belarusian”—have been problematic and unevenly applied.

- Lukashenka is no Western-style democrat, but his authoritarian power base in Minsk may ensure that Belarus avoids falling victim to the Kremlin’s imperial designs.

- The West faces a choice about whether to further isolate the Lukashenka government or re-engage with official Minsk in the hopes of altering that orientation.

- The lifting of some sectoral sanctions in return for the release of political prisoners could represent the first step in this potential rapprochement.

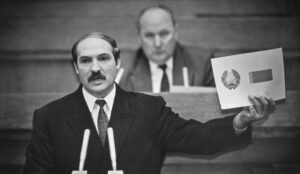

Popular cliches are often difficult and, at times, impossible to dispel. Yet, providing a more nuanced perspective on commonly misconstrued trends is critical to understanding the geopolitics of the post-Soviet space. Belarusian nationalism dates back to the 19th century and connotes people who believe Belarusians should have their own state independent from Russia. In the Belarusian context, many observers have supported the claim that President Alyaksandr Lukashenka is no nationalist. Lukashenka’s actions, against the backdrop of a delicate regional position, however, cast doubts on that notion (see EDM, January 19). In August 2020, the Belarusian leader asserted: “Independence is expensive. But it is worth preserving and passing on to future generations. Behind us is Belarus—pure and bright, honest and beautiful, hardworking, a little naive and a little vulnerable. But she is ours, she is loved. And we do not give away our beloved” (President.gov.by, August 4, 2020). The following analysis may prove useful for Belarus watchers and foreign policymakers in crafting their respective countries’ policies toward Minsk to account for the nuances of Belarusian national identity (see EDM, January 24). While Belarus remains closely tethered to Russia, Lukashenka has sought to carve out more room for geopolitical maneuvers. However, the efforts of some Western countries to further isolate Minsk, both politically and economically, may effectively reinforce Belarus’s alignment with Russia (see EDM, April 24, May 4, 2023, February 7, March 14).

The Case of Andrei Suzdaltsev

In January 2024, Nasha Niva, a mouthpiece of Belarusian “Westernizers,” published an article devoted to Andrei Ivanovich Suzdaltsev, an associate dean at the Moscow Higher School of Economics (Nasha Niva, January 13). In the context of Belarus, Westernizers lean toward the West and away from Russia and are otherwise known as Belarusian nationalists. Born in Moscow and educated in the Russian Far East, Suzdaltsev moved to Minsk back in 1993 at the age of 33 and became an active political commentator. His orientation was adamantly in favor of Belarusian-Russian integration but firmly against Lukashenka, whom Suzdaltsev characterized as a rogue politician whose skill in extracting financial benefits from Moscow outstripped his loyalty to the Kremlin. As Suzdaltsev disclosed to Yury Drakakhrust of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, he felt it was easier to communicate with Belarusian nationalists because they embraced the same ideas he did with Russia but concerning Belarus (Palityka.org, September 2012). As for the “Belarusian mainstream” (i.e., Russian-speaking Belarusians), the Russian commentator felt that the group treated him as a stranger who reacts very differently to geopolitical developments.

In 2006, Suzdaltsev wrote, “Belarus is not our ally, but simply a geopolitical mercenary hired for 7 billion dollars a year.” He likened Lukashenka to Georgia’s Mikheil Saakashvili, whom Suzdaltsev claimed was certain to betray Russia. He also called for the publicized deportation of some Belarusians from Russia (Nasha Niva, October 24, 2006). In the wake of such pronouncements, the Belarusian government revoked Suzdaltsev’s permanent residency permit and ordered that he leave the country. This intensified Suzdaltsev’s vendetta against Lukashenka, which he has since laid out in multiple speeches and publications in Russia. Still, according to Drakakhrust, Suzdaltsev has failed to convince Kremlin decision-makers to pay close attention to his views.

Drakakhrust’s portrayal is quite apt. The title of his Nasha Niva article—“For Him [Suzdaltsev], Lukashenka Is a Belarusian Nationalist”—provides the impetus for analyzing Lukashenka’s role in preserving the Belarusian nation. For most of Nasha Niva’s audience, the title is somewhat scandalous as they believe true Belarusian nationalists are those who gravitate toward Europe, oppose authoritarianism and state dominance over public property, and insist on communicating in Belarusian. Overall, the formula “pro-European + anti-authoritarian + speaking Belarusian = Belarusian nationalist” enjoys broad but perfunctory recognition among Belarusians. For his part, Lukashenka comes across as antithetical to each component. Yet is this formula well-grounded? Rather than taking this assumption for granted, a closer examination must be performed to determine where exactly Lukashenka falls with regards to Belarussian nationalism.

A Monopoly on Belarusian Nationalism?

“Nationalism” is a tricky term. In Russian, its connotation remains largely negative, almost synonymous with xenophobia. In English, “nationalism” is frequently used with a negative connotation as well, but it can also hold a neutral and more positive meaning, along the lines of dedication to a national cause. In other words, absent nationalism, there can be no nation-building.

For Belarus, the term is particularly nuanced. At least from the beginning of the Soviet era, asserting Belarusian identity has been tantamount to insisting that Belarus is distinct from Russia. Consequently, only those propagating the idea of Belarus’s detachment from Russia in favor of the West culturally and politically have been referred to as nationalists. These Westernizing nationalists discerned proto-Belarus in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, an entity consistently regarded as European, contrasted against the “barbaric” and “Asiatic” Muscovy. On the other side, the implicit or explicit followers of so-called “West-Rusism”—those who see Belarus as a separate nation but insist on recognizing the historical ethnic and cultural ties between Belarus and Russia—have never been called nationalists.

And yet, preeminent cultural Westernizer Valer Bulgakov observed in his seminal 2006 book on Belarusian nationalism, History of Belarussian Nationalism (Istoriya Belorusskogo Natsionalizma), that the first recognition of Belarusians as a self-styled nation was part of the Russian nationalist reaction to the Polish uprising of 1863. The Russians wanted to uproot Polish influences in the areas between Russia and Poland and began to pay closer attention to those inhabitants. Thus, Belarusian identity became a cultural invention of the second half of the 19th century. Bulgakov shows persuasively that Frantisek Bogushevich and later proponents of the Westernizing variety would not have succeeded as Belarusian nationalists were it not for the fact that Belarusians were first meticulously described as a distinctive group by the proponents of West-Rusism. This characterization recognized Belarusian national identity, but only as an integral part of the Russian world, something that Lukashenka now stands accused of doing.

As a result, Mikhail Koyalovich, West-Rusism’s spiritual leader, effectively became the chief promoter of Belarusian nationalism. That nationalism, writes Bulgakov, emerged on the day after the imperial region of Belarus was founded.

Colonial Belarus was ambiguous: on one hand, it was described through a standard set of colonial techniques (which enhanced Belarus’s tangibility and bestowed it with historical legitimacy); on the other hand, through successful acquisition of knowledge the ethnographic peculiarities of Belarus were being confirmed, its linguistic borders marked out, while archeologists reconstructed its history. In summary, Belarus could now be imagined (Bulgakov, 2006).

Belarus entered the 20th century as a vaguely delineated ethnographic entity that was culturally equidistant from its two neighbors, Russia and Poland. Yanka Kupala memorialized this position in his 1922 tragicomedy “Tuteishiya” (“Locals”). The play’s main character, Mikita Znosak, repeatedly switched between identities based on whoever took control of his homeland. When the Poles did, he became Nikitsiusz Znosilowski. When the Russians did, he became Nikitii Znosilov. Perhaps two of the most important characters of the play are two “scientists” who have local roots, with one Russia-leaning and the other gravitating toward Poland. Whereas the Western scientist sees his native land as an imperfect Poland and wants Belarus to become impeccably Polish, the Eastern scientist believes that Belarus is an imperfect Russia and wants it to become impeccably Russian. The vicissitudes of Belarus’s 20th-century history, almost entirely shaped by external forces, provided that the Western scientist’s view did not prevail. In other words, Belarus managed to detach itself from Poland much more effectively than from Russia.

Today, two recognized narratives of Belarusian history, the Westernizing (no longer just pro-Polish) and Russo-centric views, continue to vie for influence. The former emphasizes the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a proto-Belarusian state that waged wars with Russia. Special consideration is also given to the Belarusian People’s Republic, a quasi-state that existed for several months in 1918 under German military occupation, representing the first-ever Belarusian claim to statehood. In contrast, the Russo-centric narrative sees Belarusians as one part of the three-prong Eastern Slavic community (Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians) that took shape in Kievan Rus. This perspective considers the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic as Belarus’s first-ever experience with statehood. It views the underground guerilla movement during the 1941–44 Nazi occupation as the first truly formative experience of Belarusians as a national community. Hence, Belarusian Independence Day was established by proponents of this view on July 3, the anniversary of Minsk’s liberation from Nazi occupation.

Leaning Toward Russia

By most accounts, the Russo-centric narrative has considerably more sway on the ordinary inhabitants of the area that is now the Republic of Belarus. Russian is the predominant language of communication, and the country is closely tethered to the Russian-centered information space maintained by telephone, television, and the Internet, as well as trips to relatives and friends. According to an online survey of 1,279 Belarusians by opposition-minded analysts in August and September 2022, only 14 percent of respondents identified with “Sviadomyya” (“Aware”), a code name for Belarusian Westernizers (Belorusskaya Natsionalnaya Identichnost, December 2022). Almost 50 percent of Belarusians believed they are part of the three-prong East Slavic nation, whereas 47 percent believed Belarusians are a separate, distinct people. Close to 45 percent supported integration with Russia, whereas 36 percent did not. The online surveys undertaken by the opposition outside Belarus usually end up with a sample skewed toward opposition-minded respondents (i.e., Westernizers). This is likely because the pro-government group, on average, uses the Internet less and because many members in that group would decline to participate in a survey that bears the imprint of an opposition mindset. Odds are that the Belarusian population’s lean toward Russia is even more pronounced than these surveys reflect.

Moreover, though resilient, the Westernizing narrative has experienced four major setbacks over time. The first took place after 1928 when the Soviet government discontinued its own indigenization program that promoted the languages and cultures of titular nationalities in the Union republics. The second setback came with the 1944 retreat of the German army. The occupation authorities had played the Belarusian nationalism card and opened many Belarusian-language secondary schools. The third setback occurred in 1985, when 75 percent of Belarusians voted down the Westernizing Belarusian insignia (the flag and coat of arms) rooted in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, only to replace them with slightly modified Soviet symbols. At the time, 83 percent voted for the return of Russian as an official language of Belarus (in addition to Belarusian). The fourth debacle occurred in the wake of the August 2020 elections when most politically active Westernizers protested the results and either emigrated or were jailed (RussiaPost, January 13, 2023).

Many opposition-minded analysts often express frustrations that all too many Belarusians gravitate toward Russia even though few Belarusians are willing to take part in Moscow’s war against Ukraine. Some of the more major commentators, however, point out the necessity of maintaining a public dialogue.

- Ryhor Astapenia, director of the Belarus Initiative at Chatham House: “For many Belarusians, Russia is part of their identity and their culture. It is therefore difficult to reject them even under the influence of strong shocks caused by the unwelcome war” (Zerkalo, July 7, 2022).

- Yury Drakakhrust, commentator for the Belarusian service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty: “In our everyday life, we may often condemn the act or behavior of a person close to us, be that a relative or a friend. But does this undermine closeness, do we necessarily break off relations with such a person? Not necessarily. The same is true in relations between peoples” (Zerkalo, July 7, 2022).

- Artyom Shraibman, nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “A good attitude of Belarusians toward Russia does not stem from economy or propaganda but rather from a deeper sense of unity and community. … Whereas pro-European-minded Belarusians choose Europe based on rational … considerations, such as a higher standard of living, education, healthcare, and the rule of law in the European Union. Belarusians who choose Russia attribute their choice to more metaphysical … arguments like ‘these are our brothers’ and ‘we are the same.’ The answer to the question of whether Belarusians and Russians are one and the same people divides Belarusian society” (Zerkalo, January 18, 2023).

Altogether, Belarusians appear to be split on two grounds—identity and collective memory on the one hand and attitudes toward Lukashenka on the other. In times of political tranquility, as from 2013 to 2020, these divisions are not entirely congruent simply because, for the most part, not all Russo-centric Belarusians support Lukashenka. However, during times of crisis, these patterns tend to converge. For example, from October 2021 to May 2022, trust in the Belarusian government jumped from 38 to 48 percent and, by the fall of 2022, was as high as 61.7 percent (Briefing, January 2023). Quite a few Belarusians apparently came to appreciate that they are neither mobilized like the Russians nor bombed like the Ukrainians.

Western Policy Missing the Mark

With this split, it is hard to believe that the opposition (i.e., Westernizers) can claim to represent the entire Belarusian people. Nevertheless, this is the message the opposition consistently conveys to Western donors, and that message has hurt Minsk’s relations with the West. For example, in 2021, Julie Fisher was appointed as the US ambassador to Belarus. Critically, Minsk denied Fisher’s visa to enter the country. She ended up taking residence in Vilnius, Lithuania, where the opposition-in-exile and Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the opposition leader who claimed to win the 2020 elections, had settled. Several statements from the late foreign minister, Vladimir Makei, who championed rapprochement with the West, declared that the visa denial was conditioned on Fisher’s repeated claims that the Lukashenka government was illegitimate while dealing exceptionally with the opposition. “We want the US ambassador badly, Makei insisted, “but with this sort of rhetoric, Ms. Fisher is not welcome in Minsk” (Reform.by, April 20, 2021). Earlier, Fisher had stated, “I do not believe that any government that … so blatantly ignores the will of the people is sustainable. … We see that Belarus is increasingly moving away from sovereignty and independence, and this worries the United States” (see EDM, April 26, 2021).

Prior to 2002 and 2003, most Belarusians opted for unification with Russia (see EDM, July 29, 2020). In a June 1999 survey, 60 percent of respondents supported this course (NISEPI, September 1999). Later, Belarusians became more accustomed to statehood and better appreciated it. Still, an April 2020 survey conducted by the Warsaw-based Belarusian Analytic Workroom, headed by opposition-minded sociologist Andrei Vardomatsky, exposed a critical facet of Belarus’s vulnerability. When asked whether they were ready “to preserve the sovereignty of Belarus even at the cost of lowering the living standards of citizens,” only 24.9 percent of respondents answered positively. Over 50 percent of respondents supported maintaining the standard of living even at the cost of giving up sovereignty (see EDM, July 29, 2020). At the time, it appeared that only a quarter of Belarusians considered sovereignty an unconditional value worth defending. Four months before the August 2020 post-election protests in Minsk, these results echo those drawn from surveys in 2010 and 2013 and fly in the face of claims by the 2020 protesters that they represented Belarusian society as a whole (BISS, April 19, 2013).

For quite some time, Lukashenka and his subordinates, including late Foreign Minister Vladimir Makei and his deputy Oleg Kravchenko, had to defend Belarusian sovereignty not only from Moscow but also from several Belarusians who were not necessarily eager to yield the country’s sovereignty to Russia but were ready to acquiesce if that outcome came to pass.

Defending Belarus’s Nationhood

During his time in power, Lukashenka has repeatedly taken a stand against the Kremlin’s desire to annex Belarus. For example, on August 14, 2002, Russian President Vladimir Putin plainly suggested that each of Belarus’s seven administrative divisions (six oblasts and the city of Minsk) join the Russian Federation by 2004. Lukashenka replied that “even Stalin did not think of such an option” (HSE, August 15, 2002). The Belarusian president then reiterated this position on multiple occasions. Lukashenka has consistently opposed the establishment of a common currency within the Union State with Russia. At times, he has also initiated a rapprochement with the West as an antidote to Moscow’s expansionism. Makei, who was responsible for fulfilling that initiative, made significant progress on that path, particularly between 2014 and 2020. This was when contacts between Minsk and the West intensified, and Belarusians received more Schengen visas per 1,000 citizens annually than any other country.

Furthermore, Lukashenka repeatedly undermined Belarusian activists who were all too eager to unite Belarus with Russia. Some of these activists, such as Andrei Gerashchenko, who used to lead the Vitebsk-based nongovernmental organization Russian Home, have disappeared from public life (Regnum, November 23, 2011). Others, including Artyom Agafonov and Elvira Mirsalimova, were prevented from becoming members of the Belarusian parliament. In December 2016, three Belarusian citizens, Yuri Pavlovets, Dmitry Alimkin, and Sergei Shiptenko, were arrested for publishing articles denigrating Belarus on the Russian websites Regnum, EurasiaDaily, and Lenta.ru, respectively (see EDM, December 12, 2016). They were subsequently sentenced to five-year prison sentences with a three-year suspension. Accused of fomenting interethnic animosity by calling the Belarusian language and statehood “artificial,” they were set free after only 14 months behind bars (see EDM, February 5, 2018).

From 2014 to 2020, Lukashenka did not merely reject overly close ties with Russia. He was actively moving toward rapprochement with the Belarusian Westernizers (i.e., the opposition). This trend culminated in three pivotal episodes.

- On March 22, 2018, a public concert devoted to the centennial of the Belarusian People’s Republic was held. While the open-air concert in the park attached to Minsk’s Opera House was organized exclusively by the opposition, the fact that the event was allowed to take place pointed to a potential reconciliation between the Russo-centric side and the Westernizers.

- On May 12, 2018, a monument was erected to Tadeusz Kosciuszko in Mereczowszczyzna, Brest Oblast, the place of his birth. Symbolically, both the official green-red and the now unofficial white-red-white flags of Belarus fluttered next to each other during the opening ceremony.

- On November 22, 2019, the reburial of the remains of Konstanty Kalinowski took place in Vilnius, Lithuania. The official Belarusian delegation was headed by a vice-premier who delivered public remarks in honor of Kalinowski, a leader of the 1863–64 anti-Russian uprising on Belarusian lands.

At the time of writing, all three episodes look as if they took place in a different world. This is in part because Western sanctions on Minsk have more than undone the potential national consolidation surrounding these events and have pushed Belarus into Russia’s close embrace. The episodes, nevertheless, did take place and provide a road map for reconciliation. The so-called “soft Belarusization” policy of the time, tacitly supported by Minsk, resuscitated the fragile hopes for the Belarusian language to eventually replace Russian in everyday life.

Other developments around that time highlight that the Lukashenka government was at least somewhat open to rapprochement with the opposition and the West.

- Since 2008, monuments to the statesmen of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania have appeared in the cities of Slonim, Lepel, Vitebsk, Grodno, and Lida. Belarusian entrepreneurs often funded these landmarks with Minsk’s approval. For example, the monument to Duke Gedymin (Lithuanians call him “Gediminas”), which opened in 2019, was entirely funded by Beltex Optic, a Belarusian subsidiary of the Lithuanian firm Yukon Advanced Optics Worldwide (org, August 21).

- In 2017, Lukashenka decided to introduce visa-free travel to Belarus for the citizens of 80 countries (see EDM, January 18, 2017). More recently, he extended the visa-free travel regime for citizens of Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland, whose governments remain rather hostile toward Minsk. Lukashenka’s choice to proceed with these decrees has been instrumental in sustaining Belarus’s sovereignty in the shadow of Russia.

- The replacement of Mikhail Babich, Russia’s ambassador to Minsk, captured public attention in 2019. Babich only served in the position for eight months. Notably, he had simultaneously served as Putin’s special envoy for the development of economic ties with Belarus. When Moscow recalled Babich, some observers underscored Minsk’s increased leverage with Moscow, if only because recalling a Russian ambassador for the officially articulated reason that Babich routinely confused Belarus with a federal district of Russia was without precedent (see EDM, April 30, 2019, March 20). Lukashenka clearly stood in the way of such designs.

- In June 2020, two months before Minsk cracked down on the post-election protests, Makei issued a warning to the West: the Lukashenka regime is strong, so do not overplay your hand (see EDM, July 1, 2020). The tone and essence of that warning were seemingly in the name of salvaging ties with the West. The letter that Makei dispatched on April 6, 2022, to “some counterparts in the European Union” after Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine pursued the same goal (see EDM, April 25, 2022).

Conclusion

The popular formula used to define a Belarusian nationalist stands on shaky grounds. It is hard to avoid this conclusion based on the account of Lukashenka’s efforts in protecting Belarusian statehood. The constituent elements of that formula, other than contributing to the retention and strengthening of Belarusian statehood, are questionable in principle.

Lukashenka is obviously no Western-style democrat. Thus, a reflexive response to the assertion of his nationalism would be that Lukashenka cares not so much about Belarus and its statehood as about retaining his power. For an authoritarian and repressive leader, clinging to power is the major preoccupation and obsession. While the latter is certainly true, the political culture that sustains authoritarianism in Belarus, Russia, and many other world regions requires a separate inquiry. Without an authoritarian power base in Minsk that is well-equipped to deal with Moscow, Belarus, with its blurred identity and economic dependency on Russia, may have fallen victim to the Kremlin’s imperial designs even before Crimea did.

Other elements of the formula for defining a Belarusian nationalist are also questionable. The notion of “gravitating to Europe” is vague and selectively adopted. Similar to many of his fellow citizens, Lukashenka subscribes to the Russo-centric view of Belarusian identity. And yet, he enabled a meaningful rapprochement with the West until he realized that some Western capitals were busy facilitating a regime change. Today, largely due to Lukashenka’s maneuvering, Minsk has been able to avoid direct participation in Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Claims of the “dominance of public property” have been unevenly attributed. While major industrial enterprises in Belarus are state-run, in 2020, the private sector contributed to 54.5 percent of employment, 35.3 percent of exports, and 45 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (Ideasbank, October 11, 2023). Moreover, in the words of Pavel Daneiko, a Belarusian economist now in exile, “If a society is not imbued with a value system that agrees [on the inherent importance of] private property but certain [businesses] are still transferred into private hands,” the most likely outcome is oligarchy of the kind that exists in Russia and Ukraine. In Belarus, private businesses have not relied on former state assets but have largely grown from the ground up. Simultaneously, the general population has gradually gained a more favorable attitude toward private property (see EDM, March 19, 2019).

On “speaking Belarusian,” at least phonetically, Lukashenka, who was born and raised in a rural village, is better equipped to speak the language than most Belarusian Westernizers, who are big-city dwellers who switched to Belarusian in their 20s and 30s. The principal reason Lukashenka delivers most of his speeches in Russian is precious little popular demand for the alternative

The question of whether Lukashenka is a Belarusian nationalist is much more nuanced than the popular formula presented here would suggest. Some of Lukashenka’s past maneuvering and recent efforts to improve relations with neighbors demonstrate that Minsk seeks to maintain at least some distance from Moscow. In this context, Western policymakers face a choice between whether to further isolate the Lukashenka government, with the risk of Belarus falling deeper into Russia’s orbit, or re-engage with official Minsk in the hopes of altering that orientation. The possible signs of such a change would be a release of political prisoners, which in the current political climate could only happen by way of bargaining—namely, lifting some sectoral sanctions, for the release of some prisoners. The first sign of Western sanctions softening was the lifting European sanctions for Belshina, Belarus’s major tire producer, just days ago (Sputnik.by, March 20).

Belarusian history and its formative experiences are full of nuances, as is the present situation. Rejecting those subtleties solely in the name of democracy promotion is fraught with consequences that are counterproductive to the geopolitical orientation and, ultimately, democratization of Belarus.