Moldova’s Parliamentary Elections: European Choice Versus Russian Political Projects (Part One)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 214

By:

The pro-Europe governing coalition has won narrowly, while the Red Left has shown new strength in Moldova’s parliamentary elections on November 30. The overall political outcome, if not entirely inconclusive, is at least somewhat ambiguous.

The stakes in these elections far transcended Moldova in their significance. This was, first, a test of strength between the European Union’s magnetism and Russia’s increasingly forceful counter-action in Europe’s East.

Second (and derivative from that), this contest pitted the Moldovan coalition government, capitalizing on the Europe brand, against a resilient left-Russophile opposition. This stark polarization notwithstanding, one cannot speak of two camps in Moldova, as both sides are themselves deeply factionalized internally.

Third, Russia’s war against Ukraine and the Kremlin’s Novorossiya project (which targets Moldova via Ukraine’s southeast) shaped the external context of these Moldovan elections. The twin crises—Russia-Ukraine and Russia-EU—additionally motivated the EU to advance its Eastern Partnership vision as originally intended in Moldova.

And fourth, much more than a choice between political parties, these Moldovan elections involved a civilizational choice, as stark as the civilizational choice made in 1991—with the difference that it was largely instinctive at that time, but should have been an informed choice by now. While Ukraine did declare its civilizational choice for Europe in the October 26, 2014, parliamentary elections there (see EDM, November 3, 6), Moldova’s voters rendered a split decision, the net result of which leaves the final choice in suspension.

Within the nominally pro-Europe governing coalition, it is only its leading party—the Liberal-Democrats under Vlad Filat and Iurie Leanca—that has earned a right to the European mantle during their five years in the government (see Part Two).

The overall balance of forces has not changed in the 101-seat parliament. What has changed is the balance of rival forces within the nominally pro-Europe coalition on one side, and quite dramatically within the left-Russophile opposition.

Final returns, released by Moldova’s Central Electoral Commission, show the Liberal-Democrats with 20 percent of the votes cast and 23 parliamentary seats; the Democratic Party (controlled by billionaire Vlad Plahotniuc) with 16 percent of the votes and 19 seats; and the Liberal Party (pro-Romanian) with 9.5 percent of the votes and 12 seats. The aggregate vote for these three parties that ran under the Europe brand stands at 45.5 percent. This corresponds with an aggregate 54 parliamentary seats in accordance with the proportional system. These three parties are likely to re-constitute the pro-Europe government (Moldpres, Unimedia, December 1).

The final returns show the upstart, radical-left Party of Socialists (led by Igor Dodon) with 21 percent of the votes cast and 26 parliamentary seats, and the Communist Party (led by former president Vladimir Voronin, and more moderate than the Socialists) with 18 percent of the votes and 21 seats. The Socialists capitalized openly on the Kremlin’s support. They campaigned vociferously against the EU and for the Russia-led Eurasian project. The Communists—a Moldovan home product—followed a Euro-skeptic line while advocating for economic reliance on Russia. These parties’ aggregate vote stands at 39 percent, and they will hold 44 parliamentary seats between them (Moldpres, Unimedia, December 1).

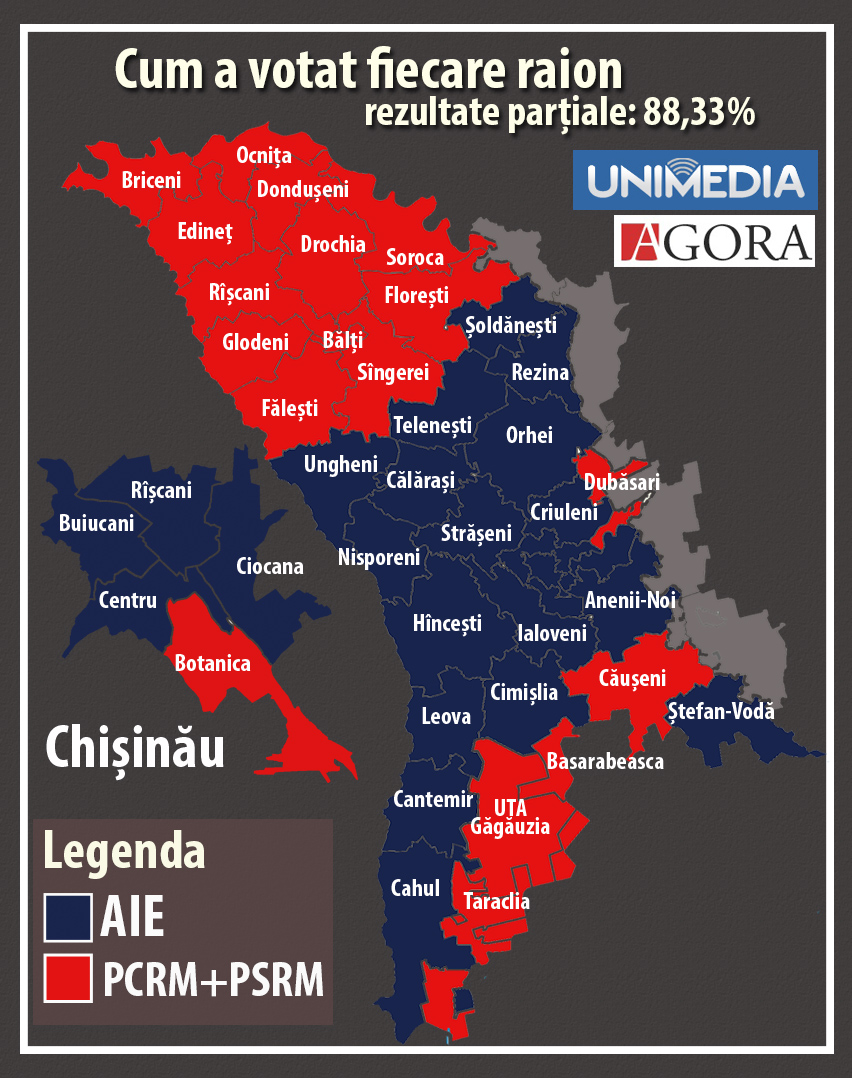

Moldova’s electoral map shows a starkly territorialized pattern of voting in these elections. The entire north of the country has voted for the Communist and Socialist opposition parties. The country’s center has voted equally compactly for the Europe brand of governing parties. The country’s south has divided along ethnic/linguistic lines, as Moldovan-majority areas voted for Europe while “Russian-speaking” areas for Russia/Eurasia. Similarly, in the city of Chisinau, the “Russian-speaking” Botanica borough has voted Left (Unimedia, December 1).

Apart from these structural factors, one incidental factor helped the Socialist Party significantly. Within the week immediately prior to the November 30 voting day, Moldova’s courts ruled to disqualify the pro-Russia party “Patria” from the election race. The court of appeals and the supreme court acted on the request of the Central Electoral Commission, which submitted evidence that this party had illegally received and spent campaign funding from “abroad” (Russia) (Infotag, November 26–29).

Led by a young Russian businessman of Moldovan origin, Renato Usatyi, and launched only ten months ago (see EDM, February 20), “Patria” campaigned for the Russian choice against the European choice, and particularly against the Liberal-Democrat Party. It also spent generously on philanthropies and star-studded pop concerts. The party’s top candidates included managers of Russian business companies and hardline communist defectors. “Patria” rose from scratch to at least 10-percent voter support and a dozen parliamentary seats projected in pre-election polls. It called for a post-election alliance with the socialists and communists (but without the “soft” Voronin). Since his party’s disqualification, Usatyi returned to Moscow, was received by a “Rossiya”-chanting crowd, and continues haranguing his supporters from there (RU1.md, accessed December 2).

Most of “Patria’s” support undoubtedly came from hardline groups of the Communist electorate. “Patria’s” disqualification just before election day undoubtedly resulted in a last-minute transfer of its supporters to the Socialist Party. This contributed to the Socialist Party’s spectacular surge over the Communists in the November 30 vote.

The Embassy of the United States in Moldova (press release, November 28) expressed its “concern” over “Patria’s” eleventh-hour disqualification (as did the international observers in their post-election assessment). This strict-constructionist view seemed to overlook the political and security risks posed by that Russian operation in Moldova. If anything, Moldovan authorities were remiss in not acting earlier on this issue.

Apart from the “Patria” issue, international observers assessed the conduct of the elections positively. The joint observation mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), and the European Parliament found that the process was generally well administered, and voters could freely and peacefully express their political “as well as their geopolitical preferences” (Joint Press Release, cited by Unimedia, December 1). With this, Moldova maintains its consistent record on free and fair elections that produce hung parliaments and dysfunctional coalitions.

*To read Part Two, please click here.