Mongolia’s Expanding Cooperation With China Has Limits

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 173

By:

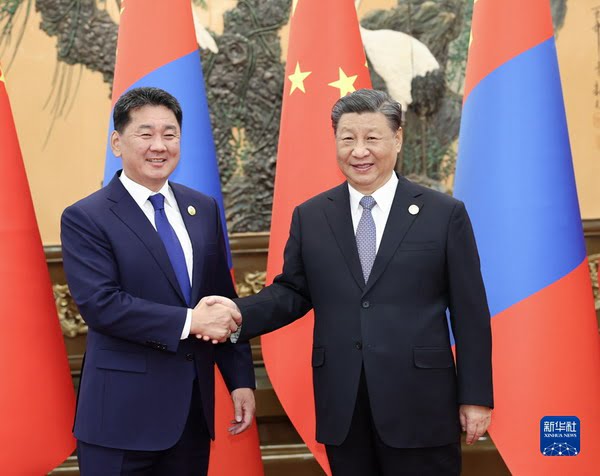

Mongolia is currently updating the country’s national security concept, and managing relations with Russia and China remains foundational (Ikon, September 27). At the end of October, Mongolian President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping met on the sidelines of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. During the meeting, Khurelsukh voiced his country’s support for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), specifically the prospects for the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline (The Diplomat, October 31). This followed the first official meeting of the Mongolia-Russia-China trilateral that was held in September to discuss regional security issues (China Daily, September 21). While these meetings address a key tenet of Ulaanbaatar’s strategy, the Mongolian government is emphasizing the need to strengthen the “Third Neighbor” concept in establishing relations with alternative partners to limit overdependence on Moscow and Beijing.

Russia and China hope to strengthen their influence in Mongolia to address potential security challenges arising from Ulaanbaatar’s evolving foreign policy. The security consultations between the three countries are driven by several factors: first, the need for more cooperation on joint infrastructure projects; second, concerns about Mongolia’s socioeconomic stability and external interference; and third, apprehensions regarding Mongolia’s expanding international engagement, particularly with the United States.

This dynamic presents opportunities and challenges for Mongolian diplomacy (Ikon, September 27). Due to its war against Ukraine, Russia has been less internationally engaged and less interested in finding new ways to cooperate. China has been quite active across a broad and expanding geopolitical agenda. For its part, Mongolia has taken more concrete steps to strengthen its relationship with China in recent months. Before the September meeting, the last security summit between Mongolia and China took place in 2015.

Mongolia and China have bolstered their relations in recent years through various initiatives. The two countries have been working together on specific projects, such as the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline as well as other energy generation, industrial production, and green energy development projects. During Mongolian Foreign Minister Battsetseg Batmunkh’s visit to China in May, the two sides discussed intensifying trade and economic cooperation, increasing bilateral trade to $20 billion, improving infrastructure at border ports, and enhancing railway connectivity (Shanghai.consul, May 1). More recently, the deputy chairman of the Standing Committee of the 14th National People’s Congress, Hui Wei, emphasized Beijing’s willingness to “cooperate more closely on road, bridge, and infrastructure projects (Eagle.mn, September 7).

The two sides seek to work in tandem on addressing global challenges and contributing to greater regional connectivity and stability (Ikon, October 16, 2022). For example, a working group was convened on September 22 to accelerate the construction of the Gashuunsukhait-Gantzmod cross-border railway. The recent event, “Days of Mongolian-Chinese Friendship,” marked the BRI’s tenth anniversary in Mongolia (Centralasia.media, September 25). On September 26, Mongolian Deputy Foreign Minister Gombosuren Amartuvshin expressed his country’s commitment to enhancing its comprehensive strategic partnership with China. Chinese Ambassador Shen Minjuan pledged to continue advancing bilateral relations and cooperation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, September 26; Mnb.mn, September 27).

The frequency of high-level visits has also picked up in recent years. In November 2022, Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh paid a visit to Beijing. The two countries officially proclaimed their strategic partnership at that time, giving special focus to Ulaanbaatar’s “Billion Trees” and “Terbum Mod” desertification initiatives. Since then, China has provided technical support, established an ecological protection zone, and offered training to Mongolian experts to combat desertification (Government Implementing Agency Forest Department, September 11). In June 2023, Mongolian Prime Minister Luvsannamsrai Oyun-Erdene embarked on an official trip to China, during which the two sides once again reiterated their mutual intentions to develop closer cooperation on regional issues (Eagle.mn, September 7).

Beijing has sought to increase its investment in Mongolia to drive key connectivity projects in the wider region. From 1990 to 2019, China invested a total of $5.4 billion in Mongolia, accounting for 19 percent of all foreign direct investment in Mongolia. Today, more than 7,543 Chinese enterprises are registered in Mongolia (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, accessed November 8). The Mongolian government has begun to align its development strategies with Beijing’s interests. Specifically, Ulaanbaatar has taken steps to line up its long-term Vision-2050 and New Revival Policy development plans with China’s BRI and Global Development Initiative (Eagle.mn, September 7).

Growing cooperation between Mongolia and China brings with it a number of difficulties. Mongolia’s challenging geography complicates its foreign relations. Ulaanbaatar is seeking to neutralize its overdependence and vulnerability on just one country. Economically, over 90 percent of Mongolian exports go to China, creating a serious trade imbalance (South China Morning Post, May 2). To mitigate this vulnerability, the Mongolian government hopes to connect with other markets in diversifying its trade policies and attracting foreign investment from additional sources.

Cultural and religious differences between the two countries may disrupt the burgeoning bilateral cooperation. For example, the Dalai Lama’s visits to Mongolia have strained relations, as Beijing and Ulaanbaatar view his position differently. The dominant religion in Mongolia is a form of Buddhism closely related to Tibetan Buddhism, and the population welcomes the Dalai Lama’s regular trips to the country. China views him as a separatist threat (General Intelligence Agency of Mongolia, accessed November 8). These differences in core principles have, at times, stoked tensions in bilateral relations.

Mongolia’s courting of alternative partners might damage its relationship with China in the future. Ulaanbaatar’s “Third Neighbor” policy aims to establish ties with Western powers to avoid excessive dependence on Russia and China. Mongolia recently elevated its relationship with the United States to the level of “Strategic Third Neighborhood Partnership,” signing agreements related to air transport and economic cooperation (Dnn.mn, accessed November 8). The “Third Neighbor” policy also emphasizes partnerships with Japan and South Korea across various sectors.

The Mongolian government’s intentions to carve out more independence in its foreign policy could serve to limit cooperation with Beijing. The fear of overdependence pushes Mongolia to prioritize building ties with countries outside the region. Ulaanbaatar’s evolving diplomacy underlines a delicate balancing act between its immediate neighbors and Western partners with a focus on improving its room for maneuver between two powerful neighbors.