Moscow Worried About Beijing’s ‘Sinicization’ of Central Asia, Caucasus

Moscow Worried About Beijing’s ‘Sinicization’ of Central Asia, Caucasus

Moscow is increasingly worried about something it has not yet figured out how best to counter: Beijing’s use of soft power to promote the “sinicization” of cultures in the countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus. This process, if successful, could lead those states to become part of a Chinese sphere of influence—and accomplish that far more fundamentally and permanently than even Beijing’s push for east-west trade routes through these regions or its involvement with local security structures. Those charges of sinicization efforts in middle Eurasia, in fact, appear to reflect an even deeper concern that Beijing may be able to use similar tactics to expand its influence into the Russian Federation east of the Urals as well as countries in Africa, Europe and the Americas, far from China’s borders.

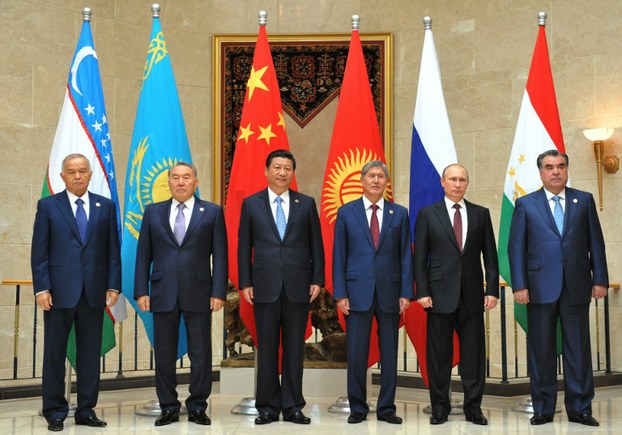

Over the last decade, the Russian government has looked on China’s economic and military advances into Central Asia with mixed feelings. On the one hand, it welcomes these Chinese moves to counter the West given Russia’s weakness. And Moscow has remained convinced that Beijing’s repressive policies in Xinjiang against Muslim minorities will prevent these countries from making any sharp turn away from Moscow toward Beijing (see EDM, April 4, 2019 and April 23, 2020; see China Brief, August 12, October 19). But on the other hand, in the last year, Moscow has grown concerned that its assumptions may not be accurate and that China will be able to use its soft power to change the cultural map of Central Asian and the Caucasus and even export its influence via such soft power strategies into Russia’s own Siberia and Far East (see Jamestown.org, August 7).

As a result, voices have begun to be raised in Moscow that China’s moves in post-Soviet Eurasia are becoming a threat to Russia. They argue Beijing’s “One Belt, One Road” (the Belt and Road Initiative—BRI) program must be countered culturally as well as economically and in the security area. And they believe the Russian side should play up what China is doing in Xinjiang in its messages to Central Asia in particular but in the Caucasus as well. Failing to do so could permit Beijing’s soft power to pry these countries out of what Moscow considers their proper Russian orbit, these observers warn (Carnegie.ru, March 25; Stoletie.ru, October 14).

Just how serious the Kremlin is taking this issue today is suggested by the work of Vita Slivak, a specialist on China at the Moscow State University’s Information-Analytic Center. Under a presidential grant, Slivak is researching “The Levers of Chinese Influence: ‘Sinification’ in Central Asia and Russia.” Most of her analysis appears to be going directly to policymakers; but she has now discussed some of her insights in two recent interviews (Casp-geo.ru, October 28; Ia-centr.ru, November 3).

Slivak noted that “ ‘sinicization’ is [an English-language] term that has begun to be used to describe Chinese influence on the politics of other countries.” It goes beyond activities like expanding trade and trade routes or cooperation in security affairs; namely, it also seeks to promote among local national cultures the idea of the centrality, if not the superiority, of Chinese culture. Furthermore, it encourages people in these countries to look to China as a global center rather than to Russia or the West, as many of them have done in the past. Beijing has made it clear that it plans to use soft power initiatives like cultural and educational exchanges and information programs everywhere it has interests. But naturally, “for the neighbors of the People’s Republic of China, as for example, for Russia and the countries of Central Asia, the strengthening of such Chinese positions is felt most sharply” (Casp-geo.ru, October 28; Ia-centr.ru, November 3).

Since 2013, the Moscow analyst explained, China has grouped these sinicization initiatives under its “One Belt, One Road” program. And the scope of its plans for such cultural change is indicated by the fact that it is already operating these programs in “more than 60 countries,” only a small number of which border China or lie along the east-west trans-Eurasian routes Beijing’s leaders say they are focusing on. That suggests, Slivak continues, that what the Chinese are doing in Central Asia and the Caucasus at present is what they are beginning to do or hope to do elsewhere in the future. Namely, that implies BRI is about far more than many have assumed. It is, indeed, a worldwide project, Slivak asserted. And it is specifically designed to realize China’s ambitions to replace all others as the paramount global power, both in particular regions such as Central Asia and the Caucasus as well as in the world as a whole. In the first case, it would displace Russia; in the second, the United States and the European Union.

Europeans are starting to recognize the nature of this danger and have shut down some of China’s Confucius Institutes on the continent, viewing them as propaganda mouthpieces for the Chinese Communist Party. As Slivak points out, Europe and the US have launched economic retaliation and trade wars against China. And most importantly, they have raised issues like Taiwan, Xinjiang and Tibet to undercut Beijing’s ability to present itself as a model others should follow. Slivak did not explicitly say so, but her message is obvious: Moscow should also push for the closure of such Chinese institutions in the former Soviet republics and limit their cultural and educational exchanges with China, and it should do the same thing in the Russian Federation as well. If it does not, the Moscow-based analyst implied, Russia may discover that, whatever its successes in countering China economically or militarily in the short term, it will find its former allies and even much of its own country “sinified” in ways that will undermine what it has achieved.

That such research in Russia is currently being supported by the Kremlin shows that at least some in the top Russian leadership are anything but happy about China’s Eurasian initiatives and want to limit the expansion of its cultural influence in the region. Whether those who hold such views will win out, of course, remains to be seen; but it suggests Moscow now recognizes that culture, more than trade or military actions, may matter increasingly in the future.