Normandy Group Micromanaging Fake ‘Election’ Preparations in Donetsk-Luhansk

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 205

By:

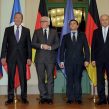

Germany’s Foreign Affairs Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier hosted a meeting of his Russian, French, and Ukrainian counterparts (“Normandy” group), on November 6, in Berlin, to lift the December deadline on the implementation of the Minsk armistice in Ukraine. This move, a foregone conclusion, may turn the armistice implementation into a protracted stalemate, with Russia holding the upper hand (see EDM, November 10).

With this move, Western powers and Russia are shifting the emphasis from the military to the political clauses of the Minsk armistice. Highly unusual for an armistice, and unprecedented among the post-Soviet era’s conserved conflicts, the Minsk documents are largely political in content, demanding of Ukraine to legalize Russia’s armed proxies through local elections and a constitutional status. This is where the emphasis has shifted in the armistice implementation process.

It was the “Normandy” top leaders’ October 2 meeting in Paris that signaled the shift. There, the Russian, German, and French leaders approved the “Pierre Morel Plan” on the legality and modalities of staging elections in “certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces” (Russian-controlled “people’s republics”). Once those elections are held and validated, the three “Normandy” powers would ask Ukraine to bring the law on “special procedures for self-administration of certain areas in the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces” (often referenced as “special status,” and meanwhile enshrined in Ukraine’s constitution) into effect. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko had termed the proposed elections “fake elections,” and the Morel document as “Mr. Morel’s personal opinion”; but Kyiv had no choice other than to enter into negotiations on this basis after the Paris summit (see EDM, October 9, 13, 29).

The process launched by the October 2 summit in Paris continued behind the closed doors of the Contact Group in Minsk and came up for review at the November 6 ministerial meeting in Berlin. There, Steinmeier listed five of the thorniest issues concerning local elections in those “certain areas” (Auswaertiges-amt.de, November 6):

1) Voter status of internally displaced persons (IDPs, their total number exceeding one million) who fled from the “certain areas” into Ukraine’s interior. Kyiv insists on securing the IDPs’ right to vote and right to seek elective office in their home localities, whereas Donetsk-Luhansk authorities would apparently disenfranchise the IDPs. Curiously, no mention is yet made of the more than one million IDPs who fled from the “certain areas” to Russia, and would presumably vote against any pro-Ukraine candidates.

2) Eligibility of political parties to enter their candidates. Steinmeier’s readout of the ministerial meeting did not go into specifics, but some of these are known. The authorities in the Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics” reject the participation of exponents of the former Party of Regions in these local elections. This territory used to be the Party of Regions’ main stronghold. However, the regime change in the spring of 2014 in Donetsk and Luhansk was far more radical than Kyiv’s regime change. The “people’s republics’ ” leaders suspect that Kyiv might work with certain Donetsk “oligarchs,” themselves “IDPs” in Kyiv at present, to return, participate in the local elections and restore some degree of Kyiv’s influence there. The “people’s republics” also reject the participation of Ukrainian far-right parties in these local elections. For its part, Kyiv wants the guaranteed participation of parties that had local branches in this territory prior to 2014. This criterion would ensure the participation of Ukrainian parties, including exponents of the former Party of Regions, while implicitly excluding far-right parties.

3) Access to Ukrainian mass media and the rules of Ukrainian journalists’ accreditation. The “people’s republics’ ” authorities want to regulate these matters themselves. Russian television channels would influence these elections most heavily, but this matter could hardly have been discussed in the Normandy format with Russia.

4) Election monitoring. Intriguingly, Steinmeier raised the question in his readout of the Normandy meeting: “Will these elections be monitored? And by whom, if not by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe [OSCE]?” Apparently, Moscow and Donetsk-Luhansk want Russia-friendly organizations—e.g., European fringe parties that monitored the 2014 Crimea “referendum” and Donetsk-Luhansk “elections”—to be invited, alongside the OSCE’s Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), to monitor and evaluate these elections, adulterating OSCE/ODIHR criteria. According to Ukrainian Foreign Affairs Minister Pavlo Klimkin, “The Russian side in the Normandy format often says that there are no definite criteria for evaluating elections. During ministerial meetings I have repeatedly shown them OSCE documents where such criteria are listed. Russia is a signatory to those documents” (Segodnya, October 23).

5) Applicability of Ukraine’s electoral legislation and role of Ukraine’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC). The earlier pretense that these local elections would be held on the basis of Ukraine’s electoral legislation (indeed, as part of Ukraine’s country-wide local elections) has been dropped. According to Steinmeier, while “Ukraine’s CEC cannot be excluded,” the legal basis would be agreed upon between “the parties [Kyiv and Donetsk-Luhansk], taking into account the Donbas region’s interests.” And according to the Quai d’Orsay’s readout of Minister Laurent Fabius’s participation in this Normandy meeting, “these elections would be based on modalities agreed upon by the parties” (Diplomatie.gouv.fr, November 6).

Russia, Germany and France will undoubtedly try to finesse these “modalities” in the Normandy and Minsk Contact Group processes. They seem prepared to stage what Ukraine characterizes as “fake elections” by technical criteria. But they skirt the fundamental issues. Elections held in the presence of Russian forces, policed by Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republic” unlawful armed formations (“people’s militia”), without legitimate courts to hear complaints, and outside the framework of Ukraine’s constitutional guarantees, would be illegitimate elections ab initio.