Russia Smashing Ukraine Into Pax Russica (Part Two)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 19 Issue: 39

By:

*To read Part One, please click here.

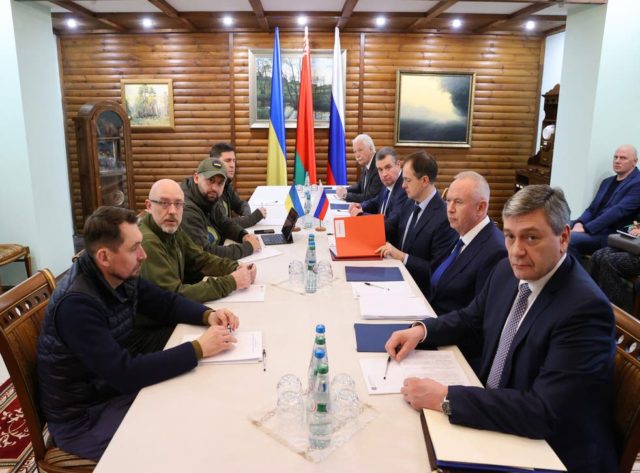

Russian-Ukrainian “peace” negotiations have been in permanent session since March 14 by video conference, with a sense of urgency and in secrecy. Multiple, specialized working groups and consultative groups meet online on a daily basis, with plenary sessions scheduled to be held on Mondays from March 21 onward. On March 21, the 26th day of Russia’s invasion into Ukraine’s interior, Kyiv’s delegates have allowed a fleeting glimpse into this process by way of expectations management in Ukraine (see below).

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy had asked Moscow directly for a ceasefire and negotiations as early as February 25, the war’s second day (President.gov.ua, February 25). Russian President Vladimir Putin refused a ceasefire unless and until Ukrainian forces lay down arms, but he consented to start negotiations with Zelenskyy’s representatives immediately (TASS, February 25). Three preliminary rounds were held face-to-face before moving into a permanent online session. Kyiv finds itself compelled to negotiate unconditionally: without a ceasefire and a pullback of Russian forces from newly occupied Ukrainian territories (see EDM, March 17).

Russia’s own political objectives have pre-determined the agenda of these negotiations. This is an inescapable consequence of Russia’s holding the military initiative with superior firepower, destroying Ukraine’s infrastructure and economy with every passing day of the war, and seizing additional Ukrainian territories. It is also a consequence of Ukraine’s Western partners’ too-little-and-too-late deliveries of military equipment to Ukraine’s embattled military. President Zelenskyy’s statements and those of his presidential office aides emphasize almost on a daily basis that Kyiv is in a hurry to make “peace” with Russia.

Kyiv officials refer to these negotiations with Russia as a “dialogue.” According to the Ukrainian delegation’s main public face, Mykhailo Podoliak, “political advisors from various countries are working as consultants alongside the main [Ukrainian] delegation to this dialogue.” Further, according to Podoliak, specialized consultative groups on legal affairs and on Ukrainian domestic politics are assisting the Ukrainian delegation. The consultants on domestic politics “are analyzing to what extent Ukrainian society would accept the outcome [of these negotiations].” The Russian and Ukrainian sides have agreed not to disclose the specifics of the framework document they are now working out (Ukrinform, March 21).

President Zelenskyy confirms, in separate remarks, Podoliak’s admission that the eventual outcome would need to be “sold” to Ukrainian society. Interviewed by multiple European public television channels on the same day, Zelenskyy said that a settlement with Russia would require changes to the Ukrainian constitution; and that he would, as president, submit those changes to popular referendums (Ukrinform, March 21).

In contrast to the Normandy and Minsk Contact Group processes (from 2014 through early 2022), the current negotiations are strictly bilateral, not mediated by any third party. Western governments and even the Russia-amenable Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) are excluded. Several international statesmen (Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, Swiss Confederation President Ignazio Cassis, the former German chancellor and Putin friend Gerhard Schröder, among others) have offered their personal services to mediate, facilitate, or host Russian-Ukrainian negotiations. President Putin, however, has turned all those offers down. Moscow insists, and Kyiv accepts, that these negotiations are a matter for the Russian and Ukrainian presidentially appointed delegations only. Zelenskyy has attempted to move the talks to a European capital and proposed a number of options, but the Kremlin turned them all down.

A strictly bilateral, non-transparent channel is tailor-made for Russian exploitation. Kyiv’s delegation is not up to the task of informing the Ukrainian or international public about what is happening in this channel. Its senior figures have no professional background in international relations or prior experience in that field. The presidential office under Andriy Yermak is the lead agency on the Ukrainian side in these negotiations and it prioritizes personal control, not institutional competence.

Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba met separately with his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, on March 10, in Turkey, attempting to set up a parallel channel. Lavrov allowed a theoretical possibility of discussing humanitarian matters (e.g., relief corridors) in such a channel in the future but ruled out any political discussions, these being reserved exclusively for the presidentially appointed delegations in the existing track (Mid.ru, March 10).

Vladimir Medinsky is Russia’s delegation chief, replacing Dmitry Kozak as the main negotiator with Ukraine. Both are Russified Ukrainians in imperial service. Kozak is currently supervising the Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics,” which Russia recognizes as “independent” and handles separately from Ukraine (see EDM, February 22). Medinsky, formerly minister of culture (2012-2020) and currently an aide to President Putin since 2020, chairs Russia’s state commissions on “historical enlightenment” (popularizing the official version of history) and on military history, tasked to fight Russia’s “memory wars.” Ukraine holds a front-and-center place in Putin’s conception of Russian history. Medinsky is certain to push for the re-imposition of Russian cultural influence in Ukraine as an integral component of any Russian-Ukrainian “peace” settlement.

President Zelenskyy and his office entered these negotiations announcing that an immediate ceasefire and the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine are Kyiv’s top priorities. Zelenskyy’s team is undoubtedly determined to resist most of Russia’s political demands. But they have come up against Russia’s tactic of sequencing the stages in a conflict-resolution process. In that sequence, fulfillment of Russia’s political conditions comes first as the precondition to withdrawing Russian forces from the country’s territory. Such sequencing was Russia’s playbook against Ukraine in the Minsk “agreements” from 2014 to 2020. It is also Russia’s playbook against Moldova on the Transnistrian conflict from 1992 to date. Russia continues applying the same tactic against Ukraine in the current negotiations.

Two weeks into the negotiations, Zelenskyy’s team seemed to acknowledge this situation. In an interview for the Polish press, also published on the Ukrainian presidential website, Podoliak stated: “Immediate ceasefire and immediate withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine’s territory is one [sic] of the key aspects of a peace agreement… Unfortunately, the process is not as fast as we would like it to be… After signing that agreement, Russia will have no choice but to begin the immediate withdrawal of its armed forces from Ukraine’s territory… Ukraine wants to spell out in detail a specific plan for the withdrawal of Russian troops, legally verify it and gain the support of international partners” (President.gov.ua, March 17).

Podoliak’s “Russia will have no choice“ is based on nothing but a nebulous reference to international law. These remarks indicate that Ukraine’s presidential office goes along with Russia’s sequencing tactic—Ukrainian political compliance first, Russian military withdrawal afterward—under the duress of a full-scale Russian war.

During the long saga of the Normandy and Minsk processes (2014–2021), Ukraine successfully resisted Russia’s demands for changes to Ukraine’s constitution. At present, however, Zelenskyy’s team considers accepting such changes and “selling” them to society. Instead of the Ukrainian democracy inspiring political transformation in Russia, Russia now stands to impose political changes on Ukraine.

Russia apparently intends to continue the war—and hold onto the newly occupied Ukrainian territories as trump cards—until exhausting Kyiv economically and militarily. At the present rates of economic dislocation and the current operational tempo, Ukraine is liable to reach the point of exhaustion earlier than Russia. The Kremlin would, at that point, expect Kyiv to satisfy Russia’s political objectives at least in their essentials (see EDM, February 22–25, March 17). These would, if accepted, severely curtail Ukraine’s sovereignty, permanently compromise its security, and reverse 30 years of nation-state-building efforts within Ukraine.

Ukraine’s Western partners can still forestall such an outcome by providing the Ukrainian military with the equipment it needs to dislodge Russian forces from the newly occupied Ukrainian territories. Failure to do so would allow Russia to wield heavy leverage for a long time to come over Ukraine and the NATO member countries in Ukraine’s vicinity.