The Cambridge Five Helped Moscow Fight Ukrainian Nationalists

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 17 Issue: 64

By:

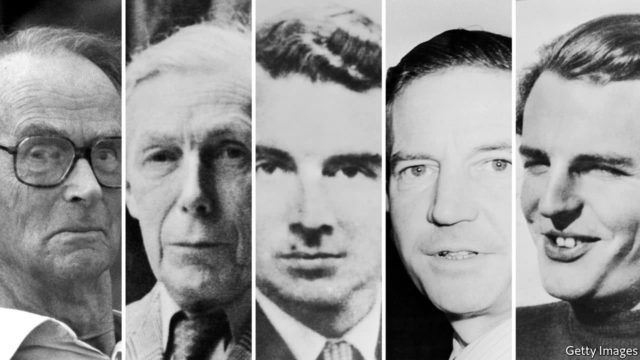

President Vladimir Putin has spent years trying to turn the Soviet victory in World War II into the central fact of Russian history. As a result, it is no surprise that Russian writers, with the encouragement of the Russian security services, have launched a variety of programs to celebrate the successes of Soviet intelligence services against both Nazi Germany and, after the war, the United Kingdom and the United States. The most frequently cited of these is Cambridge5.ru, an Internet portal devoted to the so-called “Cambridge Five,” agents of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) who penetrated British and US intelligence in the 1940s, helping Moscow steal nuclear and other secrets and counter Western moves against the USSR (Cambridge5.ru, accessed May 7). And just as the Kremlin leader’s boosting of World War II is not about the past but designed to aid Putin’s current plans, so, too, the revelations reported on this portal are almost entirely about the present and future.

The latest offering from Cambridge5.ru, which has been spread more broadly by the Russian government’s RIA Novosti press agency (RIA Novosti, April 30), is a classic example of the genre. Written by the portal’s chief editor, Veronika Krasheninnikova (a historian and member of the Russian Social Chamber), and entitled “How ‘the Cambridge Five’ Helped Hunt Down the Banderites,” it is directed at multiple audiences at once. First, the piece targets the Russians themselves, who are intended to take from it a lesson in Soviet patriotism and Western perfidy. But at the same time, the article is aimed at Ukrainians and, indeed, all non-Russians who have ever resisted Moscow; for them, the topic is clearly intended to illustrate yet another purported reason not to trust the West as well as dissuade them from holding on to any hope of escaping Moscow’s grasp if they try.

What is perhaps most immediately striking about this article, at least to a Western reader, is its tone, which overwhelmingly resembles Soviet propaganda from the darkest years of the Cold War. Krasheninnikova begins by saying that Allied relations between Moscow and the West ended with the conclusion of World War II and that, afterward, “the situation returned to the former pre-war conflict, only at a new level, with nuclear weapons and a new leader of the West, the United States, with its gigantic material resources” (RIA Novosti, April 30).

“The West did not intend to forgive the Bolsheviks for their leading one-sixth of the world with enormous natural resources and a large market left outside the sphere of capitalism,” she continues. “Worst of all,” Krasheninnikov insists, “the Soviet Union had convincingly and successful shown to the entire world a working alternative to capitalism, the socialist system; and this already was a direct threat to their capital.” To that end, the British and then the Americans exploited surviving Nazi networks in Eastern Europe against the USSR. In response, she contends, Moscow penetrated the British intelligence services and then, through them, the US ones as well in order to counter such activities. The most prominent of these Soviet agents came to be known as the Cambridge Five, a group of Englishmen recruited by Moscow in the 1930s who rose to positions of enormous influence and power after the war, putting them in a position to help the Soviet Union block Western “perfidy.”

Much of this story is well-known thanks to the memoirs of Kim Philby, one of the five. Philby had initially directed British efforts to penetrate the Soviet Union from a post in Istanbul but, after returning to an even more senior intelligence position in London, ended up delivering to Moscow information about British and US efforts to penetrate the Soviet-occupied Baltic countries (Lsm.lv, July 29, 2017 and August 2, 2017). He ultimately achieved his greatest success when he was transferred to the United States to serve as liaison with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). While in Washington, he worked closely with James Jesus Angleton, who shared with him details of US operations, unaware that Philby was passing them on to Moscow and ensuring that those Western plans failed.

According to Krasheninnikova, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the West was most interested in finding Russian émigrés who could serve as its agents in the USSR. But it was nearly as preoccupied with finding Ukrainian ones because of the importance of Ukraine within the USSR. Indeed, she says, Philby and the British had established contacts with Stepan Bandera, the Ukrainian nationalist whom she dismisses as “pro-fascist,” even before World War II. “For the CIA,” however, she writes, “Bandera was not ideal because his extreme nationalism with fascist overtones interfered with conducting subversive work inside the USSR with the Russians.” For Washington, which looked to the future, Bandera was a figure of the past and could not serve as the leader of a future Ukrainian resistance (RIA Novosti, April 30).

But the English were more interested in cooperating with him and his émigré Ukrainians. “[I]n 1949, they sent to Ukraine the first group of agents [recruited from among them] who had been supplied with radio transmitters and other secret means of communication.” They sent three more such groups in 1951, but all of them were quickly rounded up because of the information Philby and the Cambridge Five supplied Moscow. No one should be making Bandera into a national hero, as many Ukrainians now do, the editor of Cambridge5.ru says. They should see him for what Moscow believes he was: a Nazi sympathizer who was ultimately betrayed by the poor tradecraft of Western intelligence services, she asserts.