The People’s War on Drugs Rolls On

The People’s War on Drugs Rolls On

The role of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a major source of precursor chemicals for illicit drug manufacturing, particularly fentanyl and methamphetamine, is increasingly well documented (China Brief, January 19). However, the actual level of illegal drug use within China itself remains murkier. A decade ago, anecdotal accounts, official statistics, academic studies and media reports all suggested that China confronted a worsening drug abuse issue. In a 2016 report, two leading criminologists focused on China, Sheldon Zhang and Ko-Lin Chin, found that “China faces a growing problem of illicit drug use,” with the number of officially registered drug addicts hovering around 2.5 million, having increased yearly since the first government drug report in 1998. [1] However, as authorities have cracked down on crime across the board since 2018 and citizens’ movements have been more tightly restricted and tracked under the “zero-COVID” policy, the number of officially reported drug crimes and users has plummeted (Shanghai Observer, June 26, 2022).

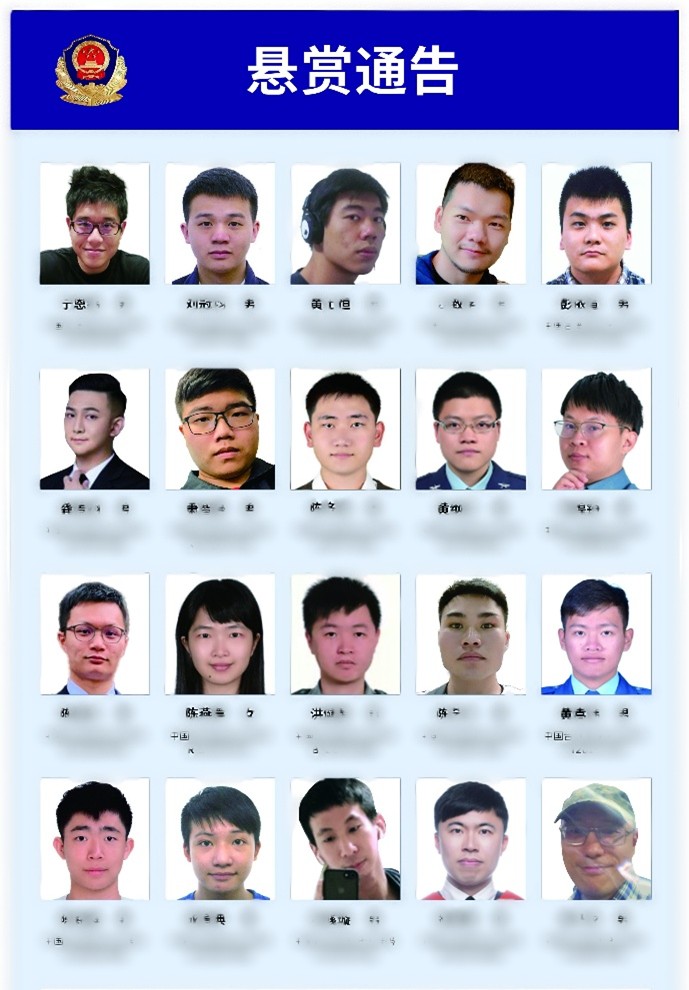

On June 26, the PRC will mark “International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking,” usually shorthanded as “International Anti-Drug Day” (国际禁毒日), with its annual wave of drug education materials and warnings to would-be narcotics users or traffickers. In advance of the day, various “anti-drug display boards” are posted online and demonstrated in schools and workplaces across the country (Ztupic, May 10; Gov.cn, June 24, 2022). State media also uses the occasion to emphasize General Secretary Xi Jinping’s contributions to “anti-drug work” (禁毒工作) and highlight the success of the political and legal affairs bureaucracy, including the public security organs, in counter-narcotics enforcement (Cpcnews.cn, June 26, 2022). For example, in 2021, CCTV’s website stressed that Xi has “always paid close attention to anti-drug work,” including personally “overseeing operations” (督战) to eradicate the scourge of illegal drugs in China (CCTV, June 26, 2021).

Falling Drug Arrests

In 2020, Xi stated that the current mix of domestic and foreign drug problems, “traditional and new illegal drug dangers” and the proliferation of drugs on and offline, pose serious threats to public safety, public health and social stability” (Xinhuanet, June 23, 2020). However, on International Anti-Drug Day last year, public security organs and state media trumpeted China’s success in drastically reducing drug abuse. At a Ministry of Public Security press conference for the release of the annual “China Drug Situation Report,” Liang Yun, head of the Ministry of Public Security’s Narcotics Control Bureau, touted drug control departments’ progress in “carrying out in depth the ‘People’s War on Drugs’” (禁毒人民战争) since the 19th Party congress in 2017 (China News, June 23, 2022). Liang said that in the previous five years, 588,000 criminals were arrested on drug crimes, but noted that drug cases had fallen successively each year, from 140,000 in 2017 to just 54,000 in 2021. He also stated that in 2021, authorities have registered around 1.49 million drug addicts, a fall of over 42 percent in a half-decade.

An article in the state-run Shanghai Observer chalks up the PRC’s success to cutting drug abuse through vigilant enforcement and strict drug prohibition (Shanghai Observer, June 26, 2022). While official sources emphasize strict drug enforcement, overall controls on population movement and extended urban lockdowns under the dynamic clearance “zero-COVID” policy, likely made illegal drug purchases more difficult for both suppliers and users.

Targeting Underworld Forces

The fall in reported drug crime in China coincides with the Chinese Communist Party’s latest periodic crackdown on organized crime, the three-year “sweep away black and eliminate evil” (扫黑除恶) campaign launched in early 2018 (Xinhuanet, February 5, 2018). These anti-crime campaigns, which have occurred at both the national and local levels throughout the Reform Era dating back to the “strike hard” (严打) campaign in 1983, seek to address what the CCP views as the negative externalities of opening up and allowing market forces a role in the economy: increased vice, criminality and organized crime. During these crackdowns, police are under increased pressure to capture criminals, which leads to spikes in arrests, but usually does not eliminate the top leadership of criminal organizations, or address the drivers of criminality (e.g., public demand for illicit services, particularly gambling and prostitution). However, the “sweep black” campaign went a step further than past crackdowns, not only targeting gangs themselves, but also going after “protective umbrellas” (保护伞)—corrupt officials that provide shelter to organized crime groups.

In their announcement launching the “sweep black” campaign, the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Justice declared that any staff of state agencies serving as “protective umbrellas” would be rooted out and severely punished (Xinhuanet, February 5, 2018). Moreover, the statement stressed that relatives and friends of individuals involved in criminal enterprises should actively persuade them to surrender or risk punishment for “harboring underworld forces.” In his 2018 anti-drug day remarks, several months into the “sweep black” campaign, Xi identified the need to eliminate official protection of drug trafficking organizations as essential to eradicating the problem, stating: “ we must resolutely destroy drug trafficking networks and dredge out drug-related underworld forces and their protective umbrellas” (Xinhuanet, June 25, 2018). The combination of more aggressive law enforcement and the constraints imposed by zero-COVID on criminal operations, many of which use legitimate businesses as fronts, undoubtedly suppressed but surely did not extinguish organized criminal activity in China, including drug trafficking.

A Problem of Unspecified Magnitude

Throughout most of the reform era, the primary illicit drug of abuse in China was heroin, largely smuggled in from weak or fractured neighboring states, especially Myanmar (U.S. Department of Justice, April 2007). However, in recent years, methamphetamine and ketamine have become the most widely abused drugs, mirroring shifts by drug trafficking organizations in Myanmar and elsewhere that have transitioned to producing synthetic drugs, particularly methamphetamine.

Due to the extreme social stigma surrounding drug use in China, harsh legal penalties and mandatory drug “treatment,” the number of officially registered drug addicts is likely a significant underestimate of the country’s total drug users. Nevertheless, the problem should also not be overestimated. Even at the ostensible peak of the methamphetamine problem in 2014, when the official number of addicts was around 2.95 million, the drug-using population in China largely comprised economically marginalized single males in urban areas, often times migrant laborers. A 2021 article in Chinese Youth Social Sciences, an academic journal sponsored by the China Youth University of Political Science, includes a survey of 2,400 young drug addicts after they underwent compulsory rehabilitation programs. [1] Of those surveyed, 84 percent were male, 88 percent were unmarried and a majority, 59 percent, lacked a high school education. As many as half of the drug abusers interviewed had experienced unemployment, with many reporting having also worked as waiters, factory workers, security guards, cooks and couriers.

Another group in which drug use became increasingly common in the 2000s and early 2010s, were wealthy young urbanites, including many celebrities. In August 2014, following a 72 percent city-wide spike in drug arrests, including many celebrities, the Beijing Trade Association for Performances published a declaration promising never to allow narcotics in the city’s entertainment industry (China Daily, August 19, 2014). Those arrested included Jaycee Chan, the son of famous movie star Jackie Chan. Police confiscated about 3.5 ounces of cannabis from Chan’s home. Notably, many of the celebrities arrested on drug charges in 2013 and 2014 were charged with possession of cannabis, which is rarely used in China, although many were also caught with methamphetamine.

Last June, the Ministry of Public Security released its annual “China Drug Situation Report,” which reinforced a picture of overall declining drug use in Chinese society noting that in 2021 the number of drugs seized by authorities, 27 tons and the number of 326,000 identified active drug users declined by 51.4 percent and 23.7 percent respectively (China Youth Online, June 23, 2022). However, the report also noted that due to interruptions in supply because of strict enforcement and likely also the zero-COVID controls on population movement, some users have been compelled to “search out alternative narcotics and psychotropic drugs or non-scheduled substances, or to become poly-drug users,” which led authorities to schedule fluoroketamine (an analogue of ketamine) and synthetic cannabinoids in 2021.

Conclusion

By North American or European standards, China’s drug abuse issue is minor. Nevertheless, the problem of illegal drug use has attracted the attention of national leaders for decades. Part of this concern is likely motivated by the notorious legacy of the illegal drug trade’s deleterious impact on China during the late Qing and Republican periods, now known as “the century of humiliation,” when opium addiction was rampant. As the use of illicit drugs was almost entirely eradicated by rigid social controls imposed in the Mao-era, the return of illegal drug use during the reform and opening period must have gravely alarmed the CCP leadership. However, in recent years, as the strategic rivalry with the U.S. has intensified, the PRC has begun to juxtapose its relatively low-levels of drug use and strict prohibition with increasingly permissive drug laws in the West (China Brief, February 2).

At the Anti-Drug Day press conference last year, Liang Yun, head of the PRC’s narcotics control bureau, stated that amidst a “global drug epidemic” China’s commitment to drug prohibition and order stands in stark contrast to the “drug chaos in the West” (西方毒品之乱形成) (China News, June 23, 2022). Of course, Liang and other top PRC anti-drug officials do not acknowledge the role that the flow of fentanyl precursor chemicals out of China—including to production facilities operated by Mexican drug cartels—has played in fueling this “drug chaos.” Moreover, while PRC officials and CCP propagandists take great pride in declaring that China does not currently experience fentanyl abuse and has not recorded any fentanyl-related deaths, examples are rare in history of drug producing or trafficking regions entirely avoiding the scourge of drug addiction (Consulate General of the PRC in New York, September 1, 2022). Here, the experience of Southeast China’s Yunnan province, which shares a long border with Myanmar and has long been a key node in international heroin and methamphetamine smuggling routes, may prove instructive. A 2018 peer-reviewed study by Chinese and international public health researchers found that while overall use of drugs (including cannabis) was lower in Yunnan than in Europe or the U.S., the rate of adult heroin usage was significantly higher than in most Western countries. [3]

The potential risk of fentanyl penetrating Chinese society suggests that for the PRC, cracking down on production and distribution of the drug and its chemical precursors serves a greater purpose than mollifying pressure from the U.S., Canada and other countries reeling from the opiate epidemic. Rather, as the PRC’s recent experience dealing with the trafficking of heroin and methamphetamine from Myanmar underscores, preventing the proliferation of fentanyl is also very much in China’s self-interest.

John S. Van Oudenaren is Editor-in-Chief of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, please reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] Sheldon Zhang and Ko-lin Chin, “A People’s War: China’s Struggle to Contain its Illicit Drug Problem,” Brookings Institute, July 2016.

[2] Wang Ruiyuan, “How Can Young Drug Addicts Make a ‘Fresh Start’?” (青年戒毒者如何“重新做人?), Journal of Chinese Youth Social Science (中国青年社会科学), Issue 6, 2021.

[3] Guanbai Zhang, et al, “Estimating Prevalence of Illicit Drug Use in Yunnan, China, 2011–15,” Frontiers in Psychiatry, June 14, 2018.