Vladimir Putin’s Mission to Beijing

Publication: China Brief Volume: 22 Issue: 2

By:

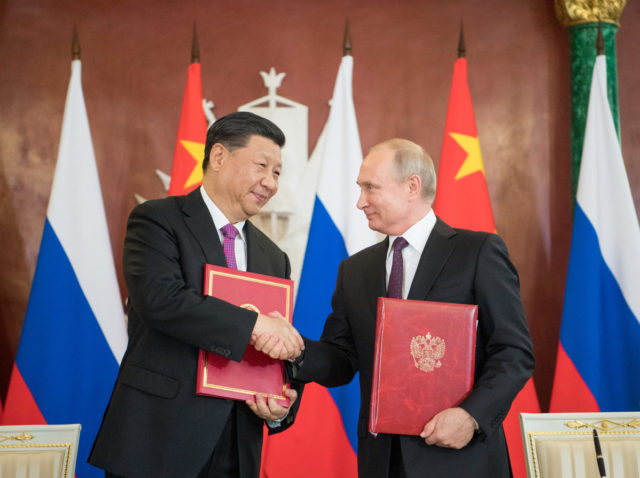

When the 2022 Winter Olympics open in Beijing on February 4, Russian President Vladimir Putin will be a guest of honor. Russia remains technically banned from Olympic participation due to doping violations, but as with the 2021 (2020) Tokyo games, Russian athletes will compete as “neutrals” under the “Russian Olympic Committee” banner. Unsurprisingly, Putin acts as if Russia is a full Olympic participant. This week, he held a videoconference with Russian athletes to wish them “triumphant performances” in Beijing (Moscow Times, January 25). Putin also decried the “politicization of sport” echoing the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) criticisms of the U.S. and other democracies for their diplomatic boycotts of the Olympics (Xinhua, January 25). During his visit, Putin and President Xi Jinping will hold bilateral talks, which will be their first in-person interaction in over two years (TASS, January 14). For Putin, the discussions will be an important opportunity to assess the extent that he can rely on support from China, before wading deeper into his confrontation with the West over Ukraine and NATO’s presence in Central and Eastern Europe.

As Russian troops mass on the Ukraine border and the odds of a major war in Eastern Europe mount, Xi faces a complex dilemma. On the one hand, he has an immediate interest in avoiding a major international crisis that could destabilize the global economy, and undermine his domestic political position in a critical year. However, he also recognizes an abiding strategic interest in sustaining and deepening the Sino-Russian partnership, which is far more viable if Russia and the West remain at permanent loggerheads. In order to reconcile these two conflicting interests, Beijing has advocated for a diplomatic solution to the ongoing crisis, while simultaneously supporting Moscow’s assertion of privileged security interests in Eastern Europe. Official Chinese sources have also plied the narrative that the U.S. and its “cold war mentality” (冷战思维, lengzhan siwei) bear primary responsibility for the current crisis, while largely casting Ukraine as a victim of geopolitical power games (Xinhua, January 27; Global Times, December 28).

Immediate Risk

On Ukraine, Chinese media and official statements have generally sympathized with Russia, but Beijing has also consistently promoted a diplomatic solution to the Ukraine situation. For example, when Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin was queried on Ukraine in December, he emphasized that China calls “for the resolution of the Ukraine crisis through peaceful means and political dialogue” and “hopes all parties can work together, earnestly follow the Minsk-2 agreement and realize peace and security in Ukraine” (FMPRC, December 9, 2021). Over a month later, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian stated that “China’s position on the Ukraine issue is consistent and clear, and remains unchanged” and noted that Beijing calls on all parties to “resolve differences through dialogue and consultation” (FMPRC, January 17, 2022). In his phone conversation with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on January 27, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi urged a “return to the 2015 Minsk Agreements” but sided with Moscow in chiding NATO for the current impasse and calling for a revision of the current European security architecture. Per Xinhua, Wang told Blinken that “Russia’s legitimate security concerns should be taken seriously and addressed,” and that “all parties should completely abandon the Cold War mentality and form a balanced, effective and sustainable European security mechanism through negotiations” (Xinhua, January 27). Wang’s remarks encapsulate Beijing’s approach to Ukraine, which is to promote a diplomatic resolution of the crisis, while rhetorically siding with Moscow against the U.S. and NATO.

2022 is a critical political year for Xi as he seeks to consolidate his hold on the top leadership positions at the upcoming 20th Party Congress this fall (China Brief, January 25). In this context, Xi is seeking to minimize both economic and political risk, which is reflected in the PRC’s dogged adherence to a zero-COVID epidemic prevention approach, as well as the Central Economic Work Conference’s establishment of stability as China’s top economic priority for 2022 (China Brief, January 14; Xinhua, December 10, 2021). For China, the costs of a major Russian escalation in Ukraine would be indirect, but still substantial in terms of their economic and diplomatic ramifications. Economically, a major war between Russia and Ukraine would be a drag on the global economy, which coupled with continued zero-COVID restrictions and regulatory uncertainty, likely render Beijing’s probable 5.5-6% yearly economic growth target unattainable (Nikkei, December 24, 2021).

The U.S., EU, and other key financial actors such as the UK , Canada and Japan, would invariably respond to increased Russian aggression against Ukraine with a major scale-up of sanctions, which puts Chinese entities doing business with Russia at risk of secondary sanctions. This has already occurred to a limited extent; in 2018, the U.S. sanctioned the Chinese Military’s Equipment Development Department for purchasing Russian SU-35 jets and S-400 missile systems in contravention of the Countering Americas Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) (State.gov, September 18, 2018). Economic interaction between China and Russia is more vulnerable to punitive action by the U.S. and EU than is often realized. Although Beijing and Moscow have largely succeeded in their efforts to “de-dollarize” bilateral trade, this has not been accomplished through internationalization of the yuan, but by switching to the euro as a medium of exchange. Around 80% of transactions between China and Russia are now conducted in euros, which as some Russian experts note, hardly obviates the risk of sanctions (Carnegie Moscow, August 2, 2021).

Another economic consideration for China is that an escalation of the Ukraine conflict would likely induce price shocks in global oil and metal markets (S&P Global, January 21). Although China’s crude oil purchases have fallen from recent peaks, it remains the world’s largest importer of crude. This week, benchmark Brent crude prices hit their highest level since 2014 breaking $90 per barrel (Oil Price, January 26).

The current crisis also imperils China’s modest, but growing diplomatic and economic ties with Ukraine. Last year, Beijing and Kyiv celebrated the 10th anniversary of their strategic partnership, lauding intensifying cooperation in the fields of business, trade, technology, agriculture, energy, infrastructure, aerospace, education and culture. Both countries cited “non-interference in each other’s internal affairs and mutual respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity and independence” as the foundations of their relationship (Xinhua, June 25, 2021). This month, Xi praised the “profound friendship between the two peoples” in a congratulatory note to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Ukraine (FMPRC, January 4). In a recent interview, China’s Ambassador to Ukraine Fan Xianrong observed that economic cooperation has deepened through the Belt and Road Initiative, and that despite COVID-19-related impediments, bilateral trade grew 31.7% over the first 11 months of 2021 to 17.36 billion U.S. dollars (Xinhua, January 15, 2021). As Beijing has sought to reduce its dependence on U.S. agricultural imports, China has turned to Ukraine to help make up the difference. For example, Ukrainian corn exports to China spiked from $26 million in 2013 to $896 million in 2019 (Carnegie Moscow, December 31, 2020).

Diplomatically, Russia’s revanchist turn has negative knock-on effects for China’s already challenged outreach to Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries. Moscow has shifted to a maximalist position demanding not only guarantees that Ukraine and Georgia never be permitted to join NATO, but a drawdown of NATO deployments in all states that have joined the security bloc since 1997 (all CEE states except Greece and Turkey) (TASS, January 21). Putin’s efforts to dictate the defense policies and relationships of sovereign European nations only heightens most CEE countries’ perceptions that their security interests are inextricably bound up with the Transatlantic alliance. For example, Bulgarian Prime Minister Kirill Petkov unequivocally rejected Moscow’s position stating that “within the framework of its NATO membership, Bulgaria makes its own decisions on what policy to pursue” and there is “no category of second-class member state in the alliance” (Bulgaria National Radio, January 21)

CEE states will continue to value China as an economic partner, but given the threat from Russian aggression, ensuring solid relations with Washington will take precedence over deepening ties with Beijing. As a result, countries in the region will likely continue to prove receptive to Washington’s concerns over China’s penetration of sensitive industries such as broadband networks. For example, Romania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Latvia and Estonia have all signed joint statements on 5G security with the U.S. (The Guardian, July 13, 2020).

The desire to maintain close ties with Washington will further dampen CEE countries’ limited enthusiasm for joining China-led multilateral groupings such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the 16+1 forum between China and CEE countries

A Partnership of Necessity

Beijing has consistently advocated a diplomatic solution to the Ukraine crisis, while also echoing Moscow’s line that the U.S. and its NATO allies bear primary responsibility for the current situation. Certainly, a Russian military invasion of Ukraine would pose immediate challenges for China, but Beijing also recognizes that its relationship with Moscow is its most consequential international partnership. Should Moscow ever sour on the relationship and shift to a more equidistant position between China and the West, the PRC would be, although albeit much stronger today, as isolated in great power politics as it was under Mao Zedong in the late 1960s (China Brief, November 19, 2021). As a result, regardless of what Russia opts to do in Ukraine, China will remain committed to sustaining a close strategic partnership with its northern neighbor.

The importance of the Sino-Russian relationship was underscored when a journalist asked Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao about a Bloomberg report that Xi had implored Putin not to invade Ukraine during the Olympics (FMPRC, January 24). Zhao dismissed the report as “made up out of thin air” and intended “ to smear and drive a wedge in China-Russia relations.” He then lauded the “mature, stable and resilient” partnership between China and Russia. Semi-official media outlets have gone further, and have castigated Washington for the current impasse. A Global Times editorial claims U.S. Foreign policy “profits from regional tensions” and that Washington uses “NATO as a tool to cannibalize and squeeze Russia’s strategic space” (Global Times, December 28, 2021).

Ultimately, the partnership between Russia and China is unlikely to wane any time soon, but the potential for coordinated, proactive Sino-Russian strategic cooperation remains limited. Given their respective interests in revising the status quo in Europe and East Asia, both Moscow and Beijing might benefit from forcing Washington to confront simultaneous foreign policy crises, perhaps at a moment of domestic political crisis in the U.S. However, the current situation underscores the intense difficulty in synchronizing Chinese and Russian strategies. For Xi, the 2024-2025 window appears more promising for a major escalation against Taiwan. At that point, Xi will be midway through his third-term, the U.S. will be in the midst of a divisive presidential election, and If the DPP defeats the KMT in Taiwan’s January 2024 election, he may feel that the political route to “national reunification” is dead. By contrast, Putin may worry that Ukraine will be a much tougher nut to crack by mid-decade, and will be navigating a sensitive political period himself with presidential elections in both Russia and Ukraine slated for spring 2024. Clearly, Russia and China are stuck with one another, but whether their strategic partnership can shift from defense to offense, remains to be seen.

John S. Van Oudenaren is Editor-in-Chief of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, please reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.