Will France’s China Gamble Endanger Transatlantic Ties?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 23 Issue: 10

By:

Introduction

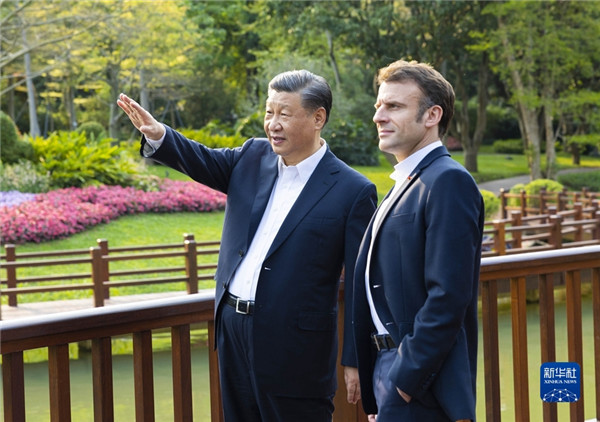

In April, French President Emmanuel Macron made a state visit to China. During Macron’s visit, the two sides signed a Sino-French joint statement that identified 51 priority areas for deepening cooperation, both bilaterally and through the EU (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs [FMPRC], April 7). Following this trip to China, Macron sought to frame Paris’s diplomatic outreach to Beijing as advancing European strategic autonomy. However, his assertions that the EU should not become involved in conflicts that are not its own and should not take cues from either a U.S. or Chinese overreaction on Taiwan generated considerable skepticism across the West (Le Monde, April 11). Nevertheless, Marcon’s comments underscore deep French distrust and skepticism with regards to allied solidarity, in terms of both the EU and NATO. As France seeks to carve out a place for itself in the multipolar international world order, Paris is making things increasingly complicated for the West by promoting European strategic autonomy under EU auspices as an alternative to NATO.

Strategic Autonomy and Western Cohesion

Long promoted by French leaders, the concept of strategic autonomy is hardly new. Moreover, Paris has had some recent success in promoting the concept as an operating principle of European foreign policy. At the EU level, the idea was first referenced by the European Commission in 2020 (European Commission, May 13, 2020) and the European Council in 2013 (European Council, December 20, 2013). Proponents of strategic autonomy argue that the EU should “be able to decide and to act without depending on the capabilities of third parties, and ensure its security of supply, access to critical technologies and operational sovereignty” (ARES, November 2016).

Although reasonable in theory, Macron’s push for European strategic autonomy glosses over the delicate balance in the current international order that is increasingly challenged by the intensifying rivalry between the U.S. and China. This new world order also calls for enhanced solidarity in the Western bloc as well as a common agenda in order to address the challenges facing democracies from the other end of the political spectrum. The signing of the 2021 Franco-Greek defense agreement is one particular example of a foreign policy decision driven by Paris’s quest for strategic autonomy. The agreement includes a pledge to interfere if one of the two countries faces aggression from a “third party” and as a result introduces a parallel, alternative security arrangement to NATO’s Article V. This is problematic in the Eastern Mediterranean, a contest region where a long-running dispute between fellow NATO members exists (Institut Montaigne, November 17, 2021). The same trend is visible in Macron’s opposition to the inclusion of non-EU NATO nations, such as the UK, in the joint procurement agreement for ammunition to aid Ukraine (Euractiv, May 3). By pushing for an EU-only supplier system to restock the bloc’s rapidly depleting stocks, Macron is leaving allied countries and Ukraine, out in the cold, in a time of crisis.

Debate is sure to persist over what constitutes an appropriate level of European strategic autonomy, but it will be far more difficult for the West to maintain its credibility vis-à-vis its strategic rivals, China and Russia, if the EU takes actions that are at odds with NATO. The contrary can lead to the deterioration of the transatlantic ties and present Beijing with what it wants to see the most: a divided Alliance.

The Spillover Effect of Sino-French Ties

While some argue that cordial Sino-French ties are founded primarily on commercial linkages, statements from both sides attach broader importance to the role of their relationship in international politics (China Daily, October 27, 2017). Official documents, such as the April 2023 bilateral joint statement, stress that the bilateral relationship encompasses broader strategic elements pertaining to international relations, such as jointly promoting world security and stability (FMPRC, April 7). Another important aspect in this regard is maintaining close communication and cooperation on the Korean Peninsula issue (Xinhuanet, April 7).

Over the past few years, the two countries have signed multiple agreements pertaining to various strategic-commercial affairs, including cooperation in the (renewable) energy segment and aviation. In 2024, France will be a guest of honor at a Chinese trade conference (Global Times, April 6). These close commercial relations have also led French administrations to take a critical view of the post-Tiananmen EU embargoes and recent sanctions on Beijing, causing tensions within the Western bloc (SIPRI, November 20, 2012).

China also factors into France’s aspirations in the Mediterranean. Cooperation with France, a leading European country and economy, can help the PRC in its efforts to make inroads in the region. The Eastern Mediterranean, in particular, is viewed by Beijing as a key link in the efforts of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to develop infrastructure linking China and European markets (State Council Information Office [SCIO], March 30, 2015). Beijing has also floated the idea of cooperating with France and Germany to develop infrastructure in Africa, a proposal which Paris has not taken up (South China Morning Post, October 22, 2021).

China has sought to exploit the potential fissures in the Western alliance created by Marcon’s attachment to strategic autonomy, rolling out the red carpet for France and other European countries (LeMonde, April 13). Moreover, establishing strategic partnerships with leading European countries such as France could provide China with access to the European defense technological industrial base, technological know-how and intellectual property. The risk, then, is that the PRC could leverage this know-how to exploit NATO vulnerabilities and accelerate its own military modernization program, thereby eroding the Western bloc’s military edge.

The ‘French Touch’ in the People’s Liberation Army

The PRC wants its military to be world-class by mid-century, which entails incorporating state-of-the-art technology into its arsenal, including high-end European weapon systems. Currently, China’s military equipment relies heavily on systems sourced from France. Most of Beijing’s helicopters are either French manufactured, such as the Airbus H160, or licensed variants of French models, like the Harbin Z-9 (Le Monde, April 7). Several of Beijing’s submarines and frigates, a vital component of its rapid naval buildup aimed at consolidating control over the South China Sea and subduing Taiwan, use engines based on German and French designs (DW, November 6, 2021). Similarly, Chinese destroyers are equipped with Thales sonars and Exocet sub-launched anti-ship missiles (Asia Times, February 4, 2022). Transferred as part of the dual use deals between the EU and China, European components, particularly the German and French systems, find a lucrative market and avoid the EU embargo. But more importantly, through incentivized imports of foreign technology, European technologies are providing the Chinese defense technological industrial base (DTIB) with an indispensable asset. In the context of growing overall trade between China and France, which grew by 16.4 percent between the first quarters of 2022 and 2023 with China’s exports to France hitting a record high of $19.3 billion, trade in dual-use items such as aircraft has also risen. For example, Chinese imports of French aircraft have increased immensely, rising 183 percent for the first quarter of 2023, on a year-on-year basis (Global Times, April 13).

The robust trade in defense and dual-use technology between France and China can mainly be attributed to the EU’s patchwork defense export controls. For China, France’s categorization of banned items is quite flexible and generous, as it only covers lethal items or complete weapon systems, and exclude dual-use technologies, which can be repurposed to serve as critical military assets (European Institute for Security Studies, October 2009). Although the recent Russian aggression in Ukraine led to the sanctioning of Chinese companies supplying the Kremlin with dual-use technologies, most of the trade linkages between the EU and China, including the traffic of dual-use technology, remain up and running (State Council of China, May 6).

Conclusion

Different perspectives on China are inevitable within the Western bloc. However, by seeking to use dialogue with Beijing as a platform for strategic autonomy, France risks undermining collective security by damaging the legitimacy and cohesiveness of the trans-Atlantic alliance. Moving forward, Macron will need to understand that a strong EU does not necessarily mean negligence and resistance towards NATO. Moving forward, France’s relations with China will become a true litmus test as to whether Macron can carry off this balancing act.

Sine Ozkarasahin is an analyst at EDAM’s defense research program. She holds a BA from Leiden University in International Studies (with a specialization in North American Studies) and a postgraduate degree in International Development (with specializations in Middle Eastern Studies and Project Management) from Sciences Po Paris. Her work at EDAM focuses on open-source intelligence analysis, drone warfare, defense economics and emerging defense technologies.