Will the North–South Transport Corridor Overshadow the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars Railway?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 14 Issue: 53

By:

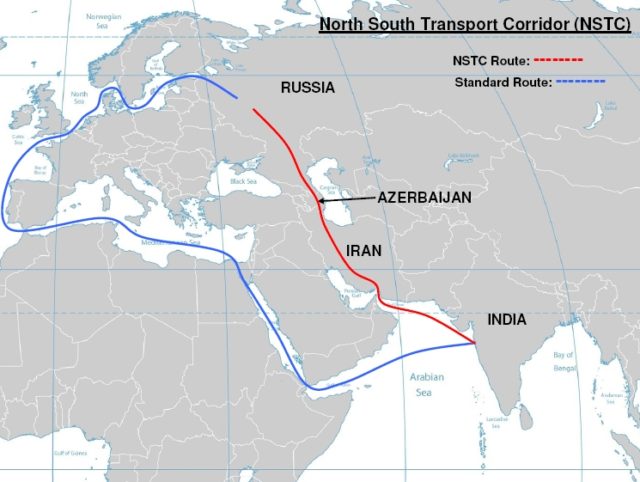

Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s official visit to Iran in early March 2017—his third in three years—was scheduled to include the testing of a section of a new railway along the Iran-Azerbaijan border. The Astara (Iran)–Astara (Azerbaijan) railroad is part of the North–South Transport Corridor (NSTC), which is currently under construction. During Aliyev’s visit, two intergovernmental memoranda of understanding (MoU) were signed. The first MoU dealt with preventing money laundering and financing terrorism. The more high profile, however, was the signed document on the expansion of railroad links (Tasnimnews.com, March 5). Iranian President Hassan Rouhani highlighted the short-term benefits of the railway for existing trade relations, which have seen a 70 percent increase in recent years due to the growth in trade in the border regions (President.ir, March 5).

The North–South Transport Corridor has become a particularly valuable project for Baku in the last two years, as it serves as a catalyst to deepen links with Iran and Russia—two major neighboring powers. The transport corridor offers significant political benefits as well as economic ones for Azerbaijan, offering the country direct access to the Persian Gulf via Iranian railways, and providing an alternative to Georgian railways and Georgia’s Black Sea ports (Georgiatoday.ge, April 1).

Another important motivating factor for Baku is that the NSTC undermines Armenia’s own regional railway initiative. Yerevan wants to connect Armenian railroads with Iran as well as further extend this rail link via Georgia to Russia. Securing the necessary $3.2 billion financing for the project proved a major problem, however. Moreover, since the NSTC connects Iran to Russia, the Iran-Armenia connection slipped down the priority list for Tehran. Additionally, for the Armenia–Iran rail corridor to ultimately connect to Russia, Georgia would need to consent to rail transport via occupied Abkhazia. This is both highly unlikely in political terms, as well as costly to implement. The economic dividends of an Iran–Armenia line are much more limited compared to what the NSTC offers all the participating countries.

For Azerbaijan, another important factor to consider is the economic future of its Nakhchivan exclave. In the NSTC, Baku sees the potential to expand the recently launched short-term project to transport pilgrims from Nakhchivan to the Iranian city of Mashhad, via Tabriz (Adyexpress.az, February 7). This could be developed into a new broader project—a railway link between Nakhchivan and Baku via Iranian territory. But such a solution would require both time and financial backing from Tehran’s own railway system engineers. Previously, another way to connect Nakhchivan and the rest of Azerbaijan was envisioned: by extending the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) rail line to the exclave region through the projected construction of a Kars–Igdir–Nakhchivan spur. The realization of both projects promises to boost the connectivity of the exclave, further safeguarding against its economic isolation.

Azerbaijan’s involvement in the North–South Transport Corridor indicates a slight shift in the country’s railway transport strategy. The BTK railroad project envisioned breaking the railway “iron curtain” in the region by connecting the Caspian region to the Black Sea and beyond to Europe—bypassing Russia and weakening its Eurasian-region transport monopoly. By contrast, the NSTC does not address Russia’s domineering regional position—indeed it strengthens Russia’s access to diversified regional transit corridors. The NSTC project also helps Iran: Tehran will gain additional economic links via its transit connection to the South Caucasus.

The full realization of the NSTC requires the construction of the Rasht–Astara railway line on Iranian territory, at a cost of $1 billion (partly financed via a loan from Azerbaijan). The construction will take a minimum of three years. Even so, the project casts a shadow over the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway project, and could further undermine the BTK. The risk to the BTK is not solely attributable to the NSTC; the former has itself suffered repeated construction delays. Initially scheduled for completion in 2014, the BTK remains unfinished. Turkish officials acknowledge that the last two years were marred by numerous problems with the BTK’s Turkish construction firms. The foreign minister of Turkey, Mevlut Cavushoglu, stated, “We have some legal problems, some companies have filed lawsuits because of it” (Mfa.gov.tr, February 17, 2016).

Against this backdrop, Ankara is largely to blame for Turkey’s diminishing role in this transport project. The lack of political will has resulted in the Turkish sections still being incomplete. The Baku–Tbilisi component and the further connection to Georgia’s port of Poti on the Black Sea are operational, and have bypassed Turkey. The Viking Train sent its first cargo from China through the Caspian to Azerbaijan and Georgia, with Draugiste, Lithuania, as the final destination in late July 2016 (Today.az, June 9, 2016). This is the so-called Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TCITR), an alternative east–west “Silk Road” branch (China, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and then through Ukraine to Europe). Turkey is technically part of both projects, and it was expected that the route would run through Turkish territory. But Ankara’s lack of progress on the BTK meant that Ukraine became the main transport destination for cargo traveling along this corridor. Kyiv even harmonized its tariffs and provided discounted rates for the TCITR partner countries’ cargo (Azernews.az, April 7, 2016). Despite expectations that the TCITR will run through both Ukraine and Turkey, it remains unclear whether the route will go through Turkey then Ukraine, or through the two countries in parallel.

So far, the overshadowing of the BTK railroad by the planned NSTC has not, as might be expected, stimulated the Turkish authorities to be more responsive. However, Azerbaijan’s slight policy shift in pushing both projects promises to bring benefits to Baku while also strengthening Iran’s and Russia’s regional positions. More importantly, despite the delays in the construction of the Turkish section of the BTK, the Baku–Tbilisi line and its connection to the Black Sea port of Poti have kept the railroad’s initial goal of connecting the South Caucasus with global markets alive—mainly thanks to the modest level of Europe-bound cargo transport across the Black Sea and via Ukrainian territory. Yet, after the completion of the BTK’s Turkish section, Ukraine’s further transit role in this project will need to be reconsidered, particularly since the BTK’s core idea was to connect with Turkish east–west railways. The extension of the Baku–Tbilisi line into Anatolia could be interpreted either as diversification or duplication, and perceptions will be defined by economic effectiveness over time.