Has Xi Jinping Become “Emperor for Life”?

Has Xi Jinping Become “Emperor for Life”?

The just-ended 19th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress has confirmed Xi Jinping’s status as China’s “Emperor for Life.” The 64-year-old “core leader” has filled the country’s highest-ruling councils—the Politburo and the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC)—with his cronies and loyalists. No cadres from younger generations were inducted to the PBSC, lending credence to the widely held belief that the 64-year-old Xi will remain China’s top leader until the 21st Party Congress in 2027 or beyond (Apple Daily [Hong Kong], October 26; HK01.com, October 25). Moreover, the fact that “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” has been enshrined in the CCP Constitution has buttressed Xi’s status as a Mao-like “Great Helmsman” for the Party and country. Projects planned for the “New Era” run into the 2030s and 2040s, which could provide Xi with a rationale to stay at the helm beyond the usual ten years. In a startling parallel to French King Louis XIV’s famous pronouncement that “I am the state” (“l’etat, c’est mois”), Xi’s near-total command of the levers of power is his way of telling all Chinese that “The Party? It is me!”

Composition of the New Leadership

In the CCP, power rests with those who can put loyal cadres in high positions. During the recent congress Xi did just that. As expected, General Secretary Xi and Premier Li Keqiang remain in the PBSC, China’s highest ruling body. The five new inductees to the PBSC, all born in the 1950s, have sworn fealty to the “supreme commander.” Li Zhanshu, Xi’s confidant and hatchet man, will become Chairman of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s parliament, next March. Party theorist Wang Huning is taking charge of the ideology and propaganda portfolio. Another loyalist, the out-going Director of the Organization Department, Zhao Leji, will head the Party’s top anti-corruption agency, the Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI). Vice-Premier Wang Yang, regarded as an economic and financial reformer, will be named Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), China’s highest advisory council. And the veteran Party chief of Shanghai, Han Zheng, is slated to be the next Executive Vice-Premier, the principal deputy to Premier Li.

The dominance of the inchoate Xi Jinping Faction (which consists of his underlings, cronies, and protégés when he worked in Fujian and Zhejiang Provinces from 1985 to 2007, as well as his classmates at Tsinghua University and fellow natives of Shaanxi Province) is most pronounced in the larger 25-member Politburo. Fifteen of the Politburo members are Xi loyalists, plus cadres who have publicly sworn total allegiance to Xi. Not counting PBSC members Li Zhanshu, Zhao Leji and Wang Huning, prominent faction members who have made it to the Politburo include the following: the Party Secretaries (PS) of Chongqing, Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin, respectively Chen Min’er, Cai Qi, Li Qiang and Li Hongzhong; the PS of Guangdong Province and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Li Xi and Chen Quanguo; Xi’s chief adviser on economic matters, Liu He; the new Director of the General Office of the Central Committee Ding Xuexiang; the just-promoted heads of the Organization and Propaganda Departments, respectively Chen Xi and Huang Kunming; and the two Vice-Chairmen of the Central Military Commission, Generals Xu Qiliang and Zhang Youxia (Radio French International, October 25; Oriental Daily News [Hong Kong], October 25).

Given that most Xi Jinping faction members are relatively young, it will take them five years (until the 20th Party Congress in 2022) before they can exert tighter control over party, government and military organs. The PBSC to be formed at the 20th Party Congress could consist of mainly Xi Faction members. However, evidence suggests that there has been some pushback to Xi’s expanding power. Xi had to make compromises regarding the wording of the CCP Constitution, and in his work report, Xi devoted space than anticipated to partially reinstating some of Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door reformist policies.

Enshrinement of Xi’s Theoretical Contributions in the Party Constitution

Xi suffered a minor setback regarding the enshrinement of his “theoretical contributions” in the CCP Constitution. Xi had wanted “Xi Jinping Thought” (习近平思想) to be inserted; this would have automatically elevated him to the same level as Chairman Mao, whose Mao Zedong Thought (毛泽东思想) has long been celebrated alongside Marxism-Leninism in the supreme document. Instead, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” was honored in the CCP Constitution as a guiding thought for the Party and state. While not quite the elevation Xi hoped for, his influence in the new document is remarkable. While the names of his two predecessors, former presidents Jiang and Hu are not in the Constitution, “Xi Jinping” is mentioned 11 times. One clause even stipulates that CCP members must “resolutely safeguard the authority of the dangzhongyang [“party center”] with Comrade Xi Jinping as core” while another admonishes Party members to “seriously study Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], October 29; People’s Daily, October 28).

Yet the ultimate test of whether Xi lives up to his preferred image as the “Mao Zedong of the 21st Century” is whether the new Helmsman can introduce comprehensive reform in political, economic and social sectors. The much-touted “Socialism with Chinese characteristics for a New Era” consists of a bevy of slogans—many of them recycled from earlier speeches by Xi—regarding China’s achievements by the year 2035 and 2050. Xi said in his opening speech of the Congress that by the year 2020, China will become a “moderately prosperous society.” The country will have attained all-rounded socialist modernization by 2035. And by 2050, China would become a “great modern socialist country” that is “prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful” (Xinhua, October 29; People’s Daily, October 28). Yet according to independent Party historian Zhang Lifan, “‘Socialism with Chinese characteristics’ is not a new concept—and merely adding the term ‘New Era’ does not give a sense that there is theoretical innovation involved.”

Implications for Economic Reforms

To realize the “New Era in Socialism with Chinese Characteristics,” Xi listed in his Congress Report fourteen policy directives. The first and most important one is to uphold “the Party’s leadership over all sectors” of the country. Party members and ordinary citizens are called upon to “self-consciously safeguard the authority of the Party’s central authorities and [its] concentrated, unified leadership.” On economic issues Xi apparently made at least theoretical concessions to Party and State Council cadres who favored a faster pace of liberalization, saying the government would “unswervingly encourage, support and provide guidance to non-state sector economic development, so that the market will take up a decisive role in the distribution of resources.” Xi changed the CCP Constitution to emphasize that the market would play a “decisive role”—and not just a “fundamental role,” as stated in the old version of the document—in the allocation of resources. In an apparent effort to lure foreign investment, the Party chief even reintroduced the concept of “national treatment,” where multinationals registered in China receive the same treatment as domestic firms (Economic Daily [Beijing], October 23; Ming Pao, October 20).

However, it is clear that the party-state apparatus’ control over different economic sectors will be enhanced, not reduced. For example, the government has started buying shares in major private firms such as Tencent; while the number of government shares are just symbolic, this could lead to the appointment of party representatives on the board of directors of these giant private companies (Radio France International, October 12; Wall Street Journal, October 11). Moreover, the reform of SOE conglomerates, which is said to be a major economic liberalization policy in the coming few years, has been slow and circumscribed. Although Beijing has pledged that these conglomerates should have mixed ownership, it is clear that the party-state will remain the major shareholder—and that the bulk of the top management will be party-state appointees (South China Morning Post, September 6; China Securities Journal, June 28). Xi’s pro-forma backing for market forces and the participation of foreign companies could provide a theoretical justification for sidelined reformers in the State Council, led by Premier Li, to lobby for a bigger role in economic decision-making.

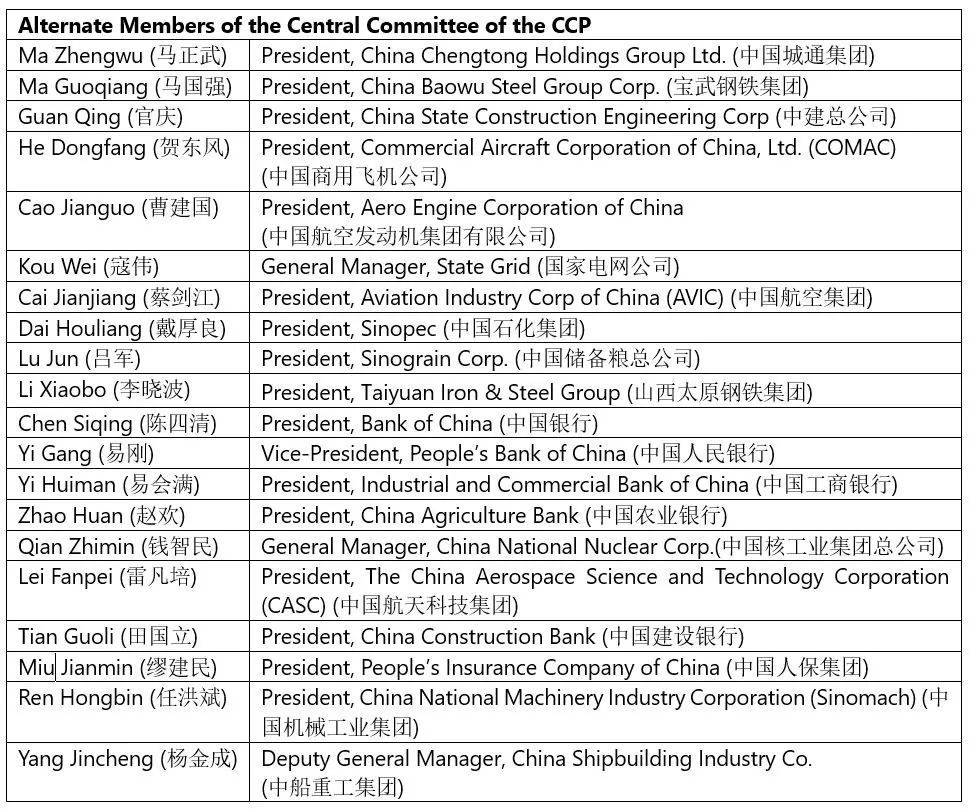

The prominence of the party-state authorities in enterprises is illustrated by the unprecedented number of SOE chiefs who have been appointed to the policy-setting Central Committee. At least twenty such state entrepreneurs have attained this rare honor of joining the policy-setting Central Committee, albeit as alternate or non-voting members (Ta Kung Pao [Hong Kong], October 25; Finance.sina.com, October 24). They include (by order of the number of votes each new alternate member gets):

The conflation of Party and business—which is the most important implication of the promotion of 20 state entrepreneurs to the Central Committee—could signal another round of “the party-state making advances, the private sector beating a retreat” in the economy.

Implications for Foreign Policy

“Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” bears striking similarities to Xi’s better-known mantra the “Chinese Dream”. Both slogans carry heavy nationalistic overtones. Xi’s goal is render China into a “great modern socialist country” by or before the year 2050. As Xi noted last week, his administration would “comprehensively push forward major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics, so as to usher in a multi-directional, multi-faceted, and three-dimensional diplomatic arrangement.” State Councilor Yang Jiechi, who is the highest official in charge of diplomacy, has been promoted a Politburo member and vice-premier, a sure sign that the Xi administration is devoting more resources to diplomacy.

Conclusion: Who Will Challenge the New “Emperor”?

While Xi has emerged as possibly the most powerful leader since Mao, it is important to note that the CCP, which has 90 million members from disparate backgrounds, is not necessarily a monolithic party. In addition to alienating members of the rival Shanghai Faction and the Communist Youth League Faction, Xi has made a tremendous number of enemies through his Machiavellian use of the anti-corruption operation to eliminate or intimidate cadres who refuse to profess full fealty to him.

At this stage, these anti-Xi elements are lying low; but they could suddenly coalesce and pounce on Xi should the latter make a terrible foreign or domestic policy blunder. Xi’s consolidation of power has significantly increased the probability that he will make such an error. As historian Zhang Lifan pointed out: “Xi wants to dictate all policies. And if he were to make a major mistake, nobody and no institutions would be able to rectify the blunder” (Central News Agency [Taiwan], October 26; BBC Chinese, October 25). For example, nationalism is a double-edged sword. Should Xi get into an ugly confrontation with the U.S. in say, the South China Sea—and should the Maoist dictator be seen as failing to stand up to the Americans—he might lose not only face but also power. His legions of enemies could seize the opportunity to oust him—or at least to deny him the feudalistic dream of being monarch for life.