Militarization of Regional Policy Leads to Decline of Federalism in Russia

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 22 Issue: 59

By:

Executive Summary:

- Russian President Vladimir Putin has increasingly relied on expansionist, militaristic foreign policy in his 25-year rule to centralize power and justify the dissolution of Russian federalism.

- Moscow has stripped regional governments of the power to economically and socially self-develop, leaving them only able to compete over which region can most effectively militarize in support of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

- The threat of reprisal and Kremlin-facilitated corruption means that regional leaders will support imperial policies prioritizing territorial expansion at the expense of internal development.

- Moscow is unlikely to voluntarily abandon its invasion of Ukraine as it serves as a distraction from problems at home and justifies increased consolidation of Moscow’s authority over the regions.

In March, Moscow passed a law that left citizens of Russia with almost no influence over municipal policy. The law, “General Principles of the Organization of Local Self-Government in the Single System of Public Power,” transfers power from individual villages and settlements to the deputy of each municipality (Pravo.gov.ru, March 20). The consolidation of municipal authority and the deprivation of their formal autonomy means that Russian citizens no longer elect local authorities, and all decisions are made instead by officials appointed by Moscow (Gorizontalnaya Rossiya, March 26). This is just one instance of Moscow taking away self-governance from the people of Russia and consolidating political authority.

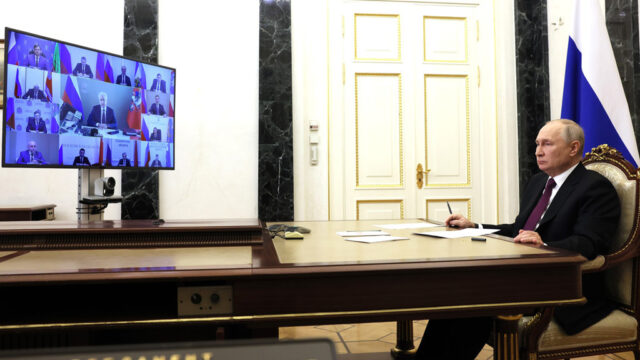

Over the course of the 25 years of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rule, the Russian Federation has increasingly become a hyper-centralized state that sees expansion as a fundamental goal. In a true federation, however, the government prioritizes the internal development of its regions. Russia’s war against Ukraine and the annexation of Ukrainian territories clearly illustrate Russia’s evolution toward hyper-centralization. In regional Russian governments, expansionism over internal governance is reflected in how all governors prioritize Kremlin militarism over protecting the interests of their own regions.

Russia’s Federal Treaty of 1992 was controversial because it established an asymmetric federation that endowed national republics with greater rights and powers than ethnically Russian regions, even though ethnically Russian regions constituted the majority of the country’s territory and population (Radio Svaboda, March 31, 2022). This enabled Moscow to maintain control over the non-ethnically Russian republics that declared their sovereignty in 1990 during Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika era. The Federal Treaty gave all of Russia’s regions a level of self-government, primarily in the economic sphere. Russian gubernatorial elections in the 1990s were relatively free compared to those under the Soviet Union, and representatives of various parties and independent candidates stood a chance of winning. The distribution of taxes between the federal center and the subjects of the federation was approximately equal, leaving the regions with the resources to self-develop.

The role of governors has changed dramatically in the past few decades—they now act not as representatives of their regions, but as implementers of Kremlin policy on the ground. When Putin became President in 2000, he established a system of the so-called “vertical of power,” emphasizing the authority of Moscow, which is fundamentally opposed to federalism (Russian State Duma, July 7, 2000; Russia in Global Affairs, April 19, 2004). In 2004, under the pretext of “fighting terrorism,” Putin abolished free gubernatorial elections and began to appoint governors from the Kremlin (Kommersant, March 29, 2020). In 2012, after a series of mass protests, Putin reinstated gubernatorial elections in a hybrid model rather than in the previous free format, candidates must collect signatures of municipal deputies, and almost all of them are members of the Putin’s United Russia party, so they do not sign for independent candidates (see EDM, January 18, 2012). Putin began appointing “acting governors” who subsequently go through elections to create the illusion of democracy (see EDM, November 20, 2017, September 19, 2018). Over time, these elections became fictitious formalities, even more so after laws blocked the participation of independent candidates (see EDM, April 2, 2019; Kommersant, March 29, 2020). Putin thereby completely subordinated the governors from all regions, republics, and oblasts to himself.

The Kremlin has revived imperial expansion to distract regions from their internal problems and lack of ability to address them as political and economic centralization have replaced federative development. Putin intends to restore a “historical Russia” that replaces the current borders of the Russian Federation with those of the Russian Empire (Posle.media, June 29, 2022). This strategy inevitably causes conflicts with other post-Soviet countries.

This distraction strategy extends to Russia’s war against Ukraine. The annexation of Crimea and support for armed separatists in Donbas in 2014 led to the rapid militarization of Russian politics (Friedrich Ebert Foundation, December 2024). The phenomenon of “inside-out federalism” arose, a method wherein Moscow used federalism as a tool to return post-Soviet territories outside the borders of the Russian Federation to Kremlin rule (The Moscow Times, February 23). Immediately after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, many Russian republics began forming battalions to fight in the war (see EDM, July 26, 2022). The regions’ race to militarize demonstrates their effective mobilization to implement the Kremlin’s neo-imperial policy. This “rethought” federalism only leaves regional governments with the right to compete, which is more actively militarizing than the ability to address local economic development and social issues (Kasparov.ru, April 1).

Russia’s national republics, which declared their sovereignty in 1990, are paradoxically staunch supporters of present-day imperial militarism. Chechnya and Tatarstan did not sign the 1992 Federative Treaty, inferring that they wanted independence, not to be part of a federation. Today, however, the leader of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, sends Chechen military units to war against Ukraine (see EDM, February 14, 2022, April 30, 2024; Kavkazr, December 11, 2024). Unlike other governors, who send contract soldiers recruited in their region and their “national battalions” under general army command, Kadyrov is allowed to have his own army because of his close relationship with Putin. Tatarstan President Mintimer Shaimiev was considered the “father of republican sovereignty” in 1990–1992, but later became a leader in Putin’s United Russia party (Business Gazeta, December 12, 2021). Shaimiev’s change in political views was likely due to Kremlin-facilitated corruption (Navalny.com, September 9, 2020; see Jamestown Perspectives, February 8). The current head of Tatarstan, Rustam Minnikhanov, actively supports the war, paying more than 5 times more than Russia’s Defense Ministry to Tartars who sign a military contract (Tatar-inform.ru, January 23).

The neighboring Republic of Bashkortostan ranks third in Russian regions, behind only Moscow and St. Petersburg, as most involved in supporting Russia’s war against Ukraine, (see EDM, April 4, 2024; Bashinform.ru, March 7). Bashkortostan’s leader, Radiy Khabirov, considers support for Russia’s war against Ukraine a priority for the republic. More soldiers from Bashkortostan have died in the war than any other region, and the local government brutally suppresses any civil demonstrations in defense of the interests of the republic and its residents (see EDM, February 27, 2024; Radio Svoboda, February 26; Mediazona, accessed April 23). The head of the Republic of Buryatia, Alexei Tsydenov, takes a similarly radical militarist position, sending Buryat soldiers to the front in droves (see EDM, April 16, 2024). Buryat men often willingly sign military contracts since the salary offered is practically impossible to earn as a civilian in the poor far eastern republics. Instead of raising the standard of living in Buryatia, Tsydenov takes the simpler route of consolidating power by repeating military propaganda and suppressing protests (Sibir.Realii, July 4, 2023).

The head of the Republic of Sakha-Yakutia, Aisen Nikolaev, dressed in a military uniform to promise contract soldiers from his republic in the occupied regions of Ukraine absolute support (Parliament of the Sakha Republic, April 4, 2024). While the head of the republic offers support to those willing to fight in Ukraine, Yakutia cannot afford to build a much-needed bridge across the Lena River because the budgeted money went to construct the Crimean Bridge (Sibreal.org, October 9, 2023). This set of priorities typifies imperial policy—the pursuit of territorial expansion at the expense of internal development. All of the leaders of ethnically Russian regions also actively support Russia’s war against Ukraine. For example, the militaristic and anti-Western rhetoric of the Novosibirsk Oblast’s governor, Andrei Travnikov, is even sharper than that of Moscow propagandists (Sibkray.ru, April 4).

At the regional level, only a few deputies have dared speak out against Russia’s war against Ukraine, and those who did were immediately repressed. The Kremlin swiftly made examples of representatives who expressed opposition to the war, designating Viktor Vorobyov, a deputy of the Komi Republic parliament who condemned Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as a “foreign agent,” thereby barring him from office (Region.expert, March 1, 2022; see EDM, April 20, 2022; Sever.Realii, October 24, 2024). The government sentenced Moscow municipal deputy Alexei Gorinov to seven years in prison for speaking out against Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in an even harsher reprisal (BBC Russian Service, July 8, 2022). Regional leaders seem to understand that any disagreement with the Kremlin on the war against Ukraine will result in a forced resignation and, at minimum, a criminal case.

Today, the Kremlin considers the number of soldiers from each region a criterion of the governor’s effectiveness (Vedomosti, January 13). Putin calls veterans of his war against Ukraine, many of whom committed war crimes, the “true elite” and promises them roles in domestic governance (Interfax.ru, February 29, 2024; see EDM, March 13, 2024). These veterans, however, often suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which, left untreated, can dispose them toward violence (DW. June 12, 2024; see EDM, July 29, September 24, November 19, 2024, February 25). Their possible rise to power may be more fraught than the rule of current governors, who, despite their verbal militarism, remain civilians.

While Moscow is bogged down in its war against Ukraine and Russian regions cannot self-govern, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is economically absorbing the Russian Far East (see EDM, April 28, 2016, February 6, 2023, January 23, May 14, 2024, March 24). In 2021, a large PRC corporation planned to build a chemical plant for methanol production in Khabarovsk Krai. Local residents, however, opposed this environmentally hazardous project in a district referendum (DW, April 2, 2021; see EDM, February 6, 2023). Today, liquidating local self-government means that such referendums are no longer possible. According to PRC diplomats, the volume of investment from the PRC into the Russian Far East is approaching 1 trillion rubles ($11,995,647,500) (Interfax.ru, January 15). This means that many Russian Far Eastern industrial enterprises, transportation, and forest lands may come under PRC control. Moscow has apparently resigned itself to this prospect, since its enormous military expenditures mean it does not have the funds left to develop the Far Eastern regions itself.

The Kremlin subsumes all internal problems to its war against Ukraine. If this war ends, a peace-time public agenda focused on domestic problems will emerge (Ridl.io, April 1). Many social and political issues in the regions will again become relevant, including the desire for substantive federalism once the Kremlin no longer has the excuse of its war for restricting autonomy. Ending the war would be risky for the Kremlin as doing so may create space for regional leaders and Russian citizens to revisit the legitimacy of Moscow’s centralized authority over the regions. This is a risk that the Kremlin is not likely to take voluntarily.