Bringing Belarus Back in From the Cold (Part Four)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 113

By:

To read Part One, please click here.

To read Part Two, please click here.

To read Part Three, please click here.

To help lessen Belarus’s economic dependence on Russia, and reach out to mainstream Belarusian society, the European Union has a range of non-political instruments available. The EU can, for example: work with the Euroclear financial services system to facilitate refinancing Belarus’s $1 billion international bond issue; agree with Minsk’s proposal to harmonize the digital markets of the EU and Belarus; explore lending and investment niches in Belarus for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank; and advance the EU-Belarus “mobility partnership” through EU visa facilitation for Belarusian citizens. One significant step has been accomplished on May 15 with Belarus’s accession to the European Higher Education Area (the Bologna Process).

The United States’ policy toward Belarus has never yet been subsumed to a strategic framework relating to Europe’s East or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) direct neighborhood. Ultimately, sanctions became a substitute for a US policy toward Belarus, along with what used to be called democracy promotion, based (as recognized tacitly by now) on poor comprehension of Belarus’s internal and external circumstances.

In 2011, however, Washington requested and received President Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s support to organize the Northern Distribution Network (NDN), serving US and NATO forces to move weaponry and supplies to and from Afghanistan. The Belarusian government worked with the US and some NATO countries to organize that two-way route, using Belarus’s railways. Military cargos, delivered by sea to Lithuania, would proceed via Belarus, bound for the ultimate destination, Afghanistan; while the equipment withdrawn from Afghanistan (including “lethal” hardware) would move in the reverse direction, via Belarus to Lithuania and its ultimate destinations in Western Europe and the US. Both Washington and Minsk have handled this massive undertaking with utmost discretion, avoiding political fallout in the US or embarrassment to Russia (see EDM, August 8, 2013). Minsk has never gone public to claim credit for this operation, which presumably continued through 2014. Whatever its eventual duration, US interest in the Northern Distribution Network is, by definition, a time-limited interest (see EDM, June 15, 2015).

Implementation of the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program in Belarus, along with safe custody of a batch of enriched uranium there, were also defined as US goals in recent years. The Belarusian government has fully cooperated with these US objectives. But these have been narrowly defined, compartmentalized goals, unrelated to a regional policy concept, which is still missing in Washington.

The United States and NATO missed the chance to build on Minsk’s proposals regarding a joint anti-chemical, anti-radiation training center in Belarus and other benign ways to substantiate the NATO-Belarus partnership program. Instead, since 2011, the Alliance has deepened the freeze on its partnership with Belarus for political reasons (see Part Three in EDM, June 15). That lost opportunity may not return any time soon. Russia’s war against Ukraine and its general belligerence seems to discourage further initiatives, however benign, in NATO-Belarus relations at present. Both sides would be wary about provoking an easily provoked Russia.

Yet Russia’s openly anti-Western posture and its regional expansionism have led Washington and Minsk to open a new diplomatic dialogue, with a view to addressing shared concerns. However belated and however slow to evolve (outpaced even now by events in the region), this dialogue confirms that ostracizing Belarus is no longer a US option. Yet, the dialogue’s level is, for the most part, the working diplomatic level (deputy assistant secretary of state and ministerial directors, respectively) and its goals seem modest at this stage. They stop short of seeking the “normalization” of relations or even restoration of full-scale diplomatic relations. Instead, the dialogue advances, in small steps, a practical nature that might, in due course, show a cumulative effect.

More urgent, perhaps, than those small steps, but invisible to the public, is the opportunity for Washington and Minsk to share their strategic assessments and threat perceptions arising from Russia’s belligerence in Europe’s East. Alluding to this, Lukashenka recently quipped, “I’m not ‘Europe’s last dictator’ anymore. There are dictators a bit worse than me, no?” (Bloomberg, April 2).

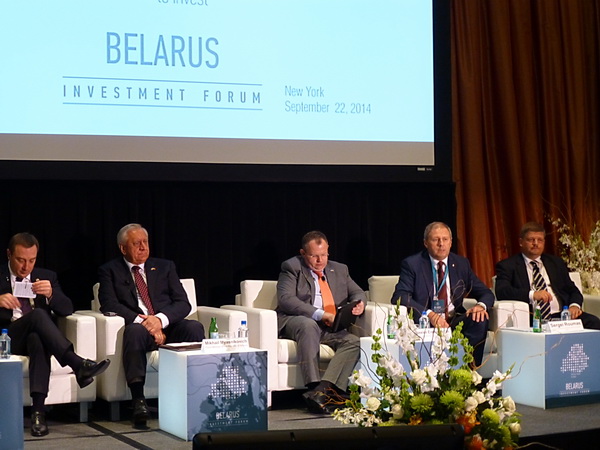

The first-ever Belarus-US investment forum was held in September 2014, in New York, with Belarus’s then–prime minister Mikhail Myasnikovich attending (see EDM, October 1, 2014). Washington and Minsk are discussing a possible increase of their respective embassy staffs (currently headed by chargés d’affaires) in the two capitals. In May 2015, in Washington, the US and Belarusian diplomats held the first round of a human rights dialogue with the aim to move from “loud” mutually accusatory statements to a quiet and honest dialogue on issues of concern. When the US White House prolonged on June 10, as expected, the sanctions against President Lukashenka and nine other Belarusians by one more year, Minsk responded in a conciliatory manner. Citing the “recent warming in Belarus-US relations,” the Ministry of Foreign Affairs observed that “it would be unreasonable to expect all controversial issues to be resolved overnight,” and hoped for “Belarus and the US to focus on what they have in common, not their differences” (Belapan, June 11).

Those commonalities, from Minsk’s perspective, must converge on support for Belarus’s state independence and sovereignty. A synergy of the United States and the European Union is essential to fostering an area of stability and prosperity, the necessary foundation for any successful reforms in this region (a view to which Ukraine and Moldova would undoubtedly subscribe). Ample scope exists for cooperation programs between Belarusian government institutions, local administrations, chambers of commerce, professional organizations and universities, with their US and European counterpart organizations. More than any country in Europe’s East, Belarus has suffered from provincial-cultural isolation from the West. This damages the country in the long term, more deeply than any political isolation of individual leaders. In the short term, however, both types of isolation erode Belarus’s capacity to handle the rising challenges from Russia.