Caspian Sea Drying Up, Forcing Coastal Countries to Respond

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 178

By:

The Caspian Sea is in danger of drying up. On June 7, government officials in the coastal city of Aktau, Kazakhstan, released a statement declaring a natural state of emergency for the maritime industry due to the sea’s low water levels (Facebook.com/Aktau_Press, June 7; Eurasianet, June 9). All five countries on the Caspian coast—Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Azerbaijan—hope to continue to exploit the fish in the inland sea and the oil and gas deposits below its surface. The littoral states are working to develop north-south and east-west transportation routes by sea that will provide transit links to China and Europe. The Caspian’s declining water levels, however, threaten these plans, reducing the capacity of its ports and access to much of the sea’s coastline due to siltation. These trends are forcing the coastal states to focus on problems they have largely ignored and to consider the possibility that falling water levels and siltation will have serious economic, demographic, geopolitical, and security consequences for the wider region (RITM Eurasia, November 11).

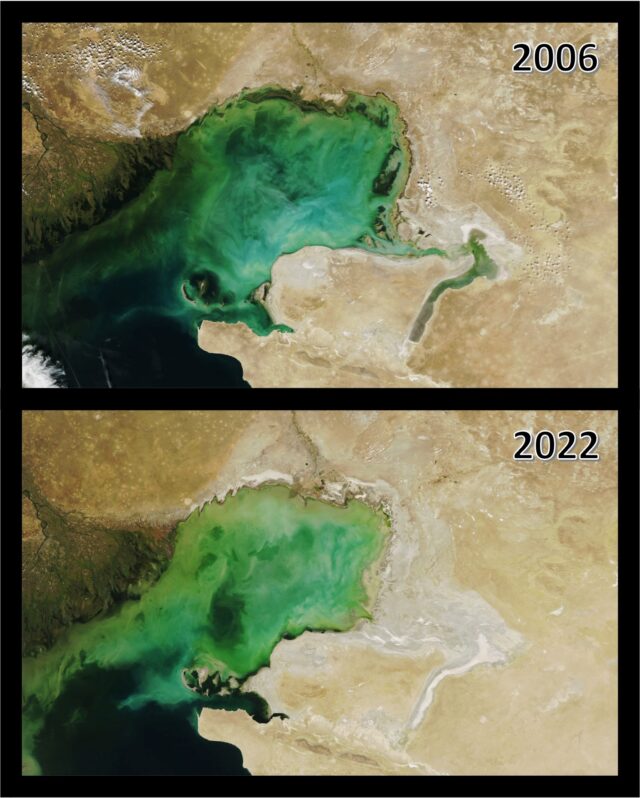

The Caspian’s water levels have declined by more than a meter and are projected to decrease anywhere from 9 to 18 meters by the end of the century. Falling water levels over the past three decades have increased the sea’s salinity and the deleterious impact of discarded sewage left untreated. Siltation near the coasts, as shown by satellite photography (see Zakon, July 12), is affecting the Caspian’s northern and southern areas. The northern portions have felt the impact of reduced transit capacity at ports in Kazakhstan and Russia. In the south, siltation is affecting Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan’s ability to operate (Voenno-politicheskaya analitica, July 13; Izvestiya, August 20; Gharysh. kz, accessed November 16). In Turkmenistan, these problems are leading to a sharp deterioration of the situation near the Turkmenbashi seaport. Some researchers there say the situation may already be worse than it is in the north (Meteo jurnal, October 2; Kaspiskii vestnik, October 13). The Turkmenbashi seaport faces stiff trade and transit competition from Kazakhstan on the sea’s eastern coast. The combination of siltation and competing oil exports spell danger for Ashgabat (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 10, 2018). These trends are also setting off alarm bells in Azerbaijan and Iran (RITM Eurasia, October 21).

The severity of potential consequences can be seen in what has already happened with the Aral Sea, where similar trends have sparked political clashes (Ia-centr.ru, August 28; QMonitor, June 7). The two most immediate consequences are the decline in the number of fish these countries can harvest and the deterioration of their populations’ health from sea winds spreading residue of rare earth minerals that had been hidden along the seabed until now.

For the governments of the littoral states, the economic and political consequences of the Caspian drying up are far more significant. Expert communities have discussed these effects for some time, and now they have become serious enough to threaten the coastal states’ economies. The problems of falling water levels and siltation are attracting attention at the highest levels. Most recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin raised these issues at the Russia-Kazakhstan summit on November 9. Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has promised to set up a special institute to study the declining water levels and determine how the coastal states can work together to counter this trend (Interfax, October 30; TASS, November 9; RITM Eurasia, November 11).

Putin has focused on developing a north-south route across the Caspian to avoid the instability of some east-west routes (see EDM, April 11, August 8). Moscow only has itself to blame for this situation, as its war against Ukraine has led to hefty Western sanctions on Russian-dominated transit routes. Tehran has followed suit, viewing the north-south route as an opportunity to transform itself into a trade hub (see EDM, June 7). The leaders of the three other coastal states—Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—have all bet on the Caspian to promote east-west trade. These countries hope this will lead to them becoming more economically and politically independent by linking with China to the east and Europe to the west (see EDM, May 19, 2022, October 26, 2022, May 18). Declining water levels and siltation make all these goals more difficult to reach.

The ecological implications of the Caspian Sea drying up are not the only dangers to the region. The competing visions between a north-south route dominated by Russia and an east-west route involving the coastal states of Central Asia and Azerbaijan are part of an intense geopolitical competition. Trade wars and the provision of sufficient military force to ensure that ships passing along one axis will not be disrupted by those transiting along the other hurt regional stability (see EDM, October 16, 2020, March 23, 2021). Russia remains the dominant power in the Caspian, though its influence is fading. Its Caspian Flotilla is no longer the only force that matters. Moscow’s extensive use of ships in its war against Ukraine and for transit through the Volga-Don Canal have further reduced Russian dominance (see EDM, May 31, 2018, April 13, 2021, June 24, 2021).

This competition has intensified in recent months, as the decline in water levels and siltation reached their peak. All five littoral states are at least willing to discuss how to limit the further impact of these trends on fishing and biodiversity. They have held a series of joint meetings on the subject but have yet to develop a formal agreement on actions that need to be taken (Interfax, December 26, 2022). More productive have been discussions between the local governments of the coastal regions within each of these countries. The talks, however, have yet to come up with any workable solutions that all parties could agree on (Kacpickii vestnik, November 2).

An air of despair has taken over many observers due to the potential wide-ranging consequences of the Caspian drying up and the similar experience with the Aral Sea. Some analysts are now couching these developments in apocalyptic terms. They suggest that the situation with the Caspian, if not reversed in the near future, will hurt the economies of the littoral states and torpedo many of the plans for the planned north-south and east-west trade routes that would cross its surface (Novye Izvestiya, June 3, RITM Eurasia, November 1). Such talk is premature. Even so, the declining water levels are already affecting the transit capacity of ports in Russia, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan and threaten to do the same in Azerbaijan and Iran in the near term. This suggests that the coastal states cannot ignore this ecological trend when evaluating regional economic and political projects for the foreseeable future.