China and the Myanmar Junta: A Marriage of Convenience

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 6

By:

Introduction

On February 1, the Myanmar military (also known as the Tatmadaw) staged a coup to overthrow the democratically elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government and subsequently imposed a year-long state of emergency. NLD leaders, including State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, have been detained along with thousands of pro-democracy activists (Mizzima, February 1). Several countries like the United States condemned the coup and expressed “deep concern” about the situation (Scroll, February 1). In comparison, China’s response has been rather muted. The state-run Xinhua news agency referred to the coup as “a major cabinet reshuffle” and neither condemned nor expressed concern about the unfolding events (Xinhua, February 2). The Chinese Foreign Ministry merely said that all parties should “properly handle their differences” and “maintain political and social stability” (PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, February 3). China blocked a United Nations (UN) Security Council statement condemning the coup and refused to criticize the human rights situation at the UN Human Rights Council, saying, “What happens in Myanmar is essentially Myanmar’s internal affairs” (India Today, February 3; The Irrawaddy, February 13).

China is Myanmar’s top trade partner and second-largest investor. It is widely expected to maintain normal bilateral relations with the junta, as it did during the 1988-2010 period of military rule. However, the road ahead for Beijing is not without challenges. The Tatmadaw’s relationship with China has never been simple, and its suspicions of China’s intentions remain strong. An examination of the relationship between the two during previous periods of military rule provides insights into what may lie ahead.

Suspicion of Chinese Intentions

The Tatmadaw is a highly nationalist force that sees itself as the custodian of Myanmar’s unity and territorial integrity. As a result, it is wary of foreigners and particularly suspicious of China, given the much larger neighboring country’s role in the many armed insurgencies—communist and ethnic—that have wracked Myanmar for decades. Until the late 1980s, the Chinese government provided political and material support, training, strategic advice and even fighters to the Communist Party of Burma (CPB).[1] This had a significant impact on the Tatmadaw’s perception of China. Senior generals believed that “the China-backed CPB insurgency” (1948-1989) jeopardized Myanmar’s sovereignty.[2] Chinese support to the CPB fueled later ethnic insurgencies in Myanmar as well, because most of the CPB cadres were drawn from alienated ethnic groups such as the Kachin, Shan, Wa, and Kokang living in the Sino-Myanmar border regions. After the CPB fell apart, dozens of ethnic armed organizations emerged out of it.[3] Among these armed ethnic groups is the United Wa State Army (UWSA), a long-time recipient of advanced Chinese weaponry and training that is still used by China to pressure the Myanmar government by proxy (The Irrawaddy, April 23, 2019).

Chinese support for armed organizations today may not reach the same levels provided to the CPB decades ago. Still, groups like the UWSA, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the Arakan Army (AA) continue to enjoy Chinese economic support, patronage and sanctuary (The Irrawaddy, July 3, 2020). This has kept alive the Tatmadaw’s suspicions of Beijing.

Courting China

The Tatmadaw’s wariness of foreigners saw it adopt an isolationist policy of equidistance between the big powers during the 1962-1988 period of military rule. In 1988, the junta instituted violent crackdowns against mass pro-democracy protests in Myanmar . In a sharp rebuke, the international community imposed sanctions and suspended economic aid. Myanmar’s already weak economy plunged into a crisis. With the survival of the regime in peril, the junta turned to China. Beijing—which at the time was also facing global isolation over its brutal Tiananmen Square crackdown—offered the desperate junta a lifeline and used its veto power to shield Myanmar from condemnation at the UN.

Beijing supported Myanmar by providing easy loans and technical expertise as well as much-needed arms sales that the generals used to beef up internal security. Trade grew from $9.51 million in 1988 to $4.4 billion in 2010, according to official Chinese figures. The security relationship deepened as well. The junta purchased arms worth $1 billion from China in 1989—the largest weapons deal in Myanmar’s history. Another defense deal worth $400 million followed in 1994. During this period, China also helped Myanmar rebuild and modernize several commercial harbors and naval facilities.[4] The military junta was able to consolidate its power behind the protective shield that China extended to Myanmar during the 1990s, although ongoing challenges in border security and smuggling continued to dog the bilateral relationship.

Following the (contested) election of a military-backed civilian government in 2010, China and Myanmar elevated their relationship to a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership,” and began supporting each other in international fora such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (PRC Embassy in Myanmar: May 28, 2011; November 16, 2011). At the same time, China also began facing competition for investment in Myanmar from other countries such as the U.S. and Japan as the country began to gradually reopen (China Brief, February 23, 2016)

Expanding Chinese Influence

China’s downplaying of the gravity of the military takeover coupled with its reluctance to censure the junta indicate that—as in the past—it will stand by the Tatmadaw. It can be expected that China will use its veto power to prevent further sanctions on Myanmar at the UN Security Council. With UN Security Council sanctions unlikely to make headway, Western governments have simultaneously pursued alternative measures to pressure the military. There are plans to prevent the junta from accessing oil and gas revenues paid into and held by foreign banks (Business Line, March 8). Washington is said to have frozen $1 billion of Myanmar government funds held in the U.S. The U.S. and the EU have imposed sanctions targeting military leaders and their kin, along with corporate entities affiliated with the junta (U.S. State Department, accessed March 22; European Council, March 22). Some foreign companies and investors have begun distancing themselves from two sanctioned entities, the Myanmar Economic Holdings (MEHL) and Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), in particular (Channel News Asia, February 5; Business Standard, March 5).

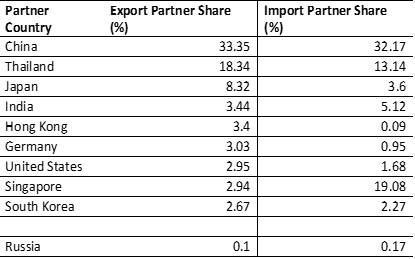

Yet because of China’s continuing support for the new regime, the impact of sanctions on foreign direct investment (FDI) into Myanmar is expected to be limited. Over the past decade, the U.S. and EU accounted for just 0.6 percent and 6.5 percent respectively of FDI in Myanmar (East Asia Forum, May 27, 2020). By comparison, China accounts for roughly a third of FDI (Global Times, January 14, 2020). China does $5.5 billion worth of annual trade with Myanmar and accounts for roughly a third of both its export and import markets. In contrast, the U.S. is not an important trade partner even after the lifting of sanctions in 2016. Still, Western sanctions would adversely affect investment in Myanmar from other Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Singapore and India, undermining their capacity to balance China’s huge presence in Myanmar’s economy (The Irrawaddy, March 3; World Bank, accessed March 17). As a result, China stands poised to gain from Western sanctions; its substantial role in Myanmar’s economy will likely grow as other regional powers are shut out.

Chinese Leverage and Infrastructure Projects

The continuing promise of economic and political support on the international stage could enhance Beijing’s already-significant leverage over Myanmar. Analysts have raised the possibility of China trying to get the ruling junta to lift the suspension on the $3.6 billion, China-funded Myitsone power project (Foreign Policy, February 23). There are early signs that the Tatmadaw may do so. On February 15, the new Chairman of the State Administration Council of Myanmar Min Aung Hlaing, who also serves as the commander-in-chief of Myanmar’s Defense Services, announced the restart of stalled hydropower projects and potentially paving the way to lift the suspension of the controversial Myitsone project as well (ANI, February 28). China can be expected to use its leverage over the junta to push through Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects that the previous government rejected. After coming to power in 2016, the NLD approved just nine of the 38 BRI-linked infrastructure projects that Beijing had proposed. It also scaled down the Kyaukpyu deep-sea port project, as the version envisioned by China did not sufficiently benefit Myanmar (China Brief, April 24, 2019). Amid the current chaos, China could try to push the junta to approve these previously rejected BRI projects.

Other Options

At the same time, the Tatmadaw’s suspicions of Chinese intentions remain strong. It was unsettled by Aung Sang Suu Kyi’s growing closeness with China during the years of NLD rule (Nikkei Asia, March 5). The military has reportedly also been upset by Beijing’s continued support to anti-Myanmar terror groups, including the AA and the UWSA, behind the mask of “facilitating peace talks” (Economic Times, September 16, 2020). Last June, for instance, Min Aung Hlaing drew attention to “strong forces” backing terror groups like the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and AA, apparently implying Chinese support (The Irrawaddy, July 3, 2020). Given its continuing distrust of Beijing, the junta will avoid deepening dependence on China as much as possible.

The Tatmadaw also has other options for shoring up international support. It has built strong defense ties with India and Russia in the last decade (The Diplomat, February 8; Nikkei Asia, February 9). Although Myanmar purchases 49 percent of its weapons from China, Russia and India have also emerged important weapons suppliers following the start of military modernization efforts in 2011. According to one estimate, Russia and India provided 16 percent and 14 percent respectively of Myanmar’s foreign arms purchases between 2015 and 2019 (SIPRI, March 2020). Like Beijing, Moscow provided political cover for Myanmar at the UN in 2007 and 2017 and has recently signaled its support for the junta, calling the coup “a purely domestic affair” (Observer Research Foundation, March 2; The Irrawaddy, February 13). Unlike China, Russia is a distant power. It does not have a history of conflict with Myanmar and the bilateral relationship evokes fewer suspicions. At the same time, too much must not be read into Russia’s role in Myanamar. Overall engagement is limited, and Russia does not even figure among the top ten investors in Myanmar. Still, with confirmed Russian support at the UN Security Council, the military junta would have a reduced need for China’s veto power and could feel less pressure to concede to China’s BRI demands.

Security Concerns

China is concerned about the instability and unrest in Myanmar. Anti-coup protests are showing no signs of abating and have also included anti-Chinese elements (The Irrawaddy, March 8; Rappler, March 15). Continued unrest would jeopardize China’s many state and private investments in Myanmar and would at a minimum slow down the implementation of projects. Many in Myanmar believe that Beijing had a hand in the coup and is providing the junta with the technical know-how to block social media and access the personal data of pro-democracy activists. Protestors have been staging rallies outside the Chinese Embassy in Yangon and are calling on the Chinese government to stop supporting the junta (The Irrawaddy, February 15).

Revival of the Myitsone project will intensify anti-junta and anti-China protests. The project is unpopular not just in the Kachin state but across Myanmar. It is a symbol of China’s extractive economic cooperation with Myanmar and a lightning rod that will attract protestors from across the country. Under these circumstances, the junta is likely to avoid reviving the Myitsone project. It needs to first quell mass protests to ensure regime survival. Reviving Myitsone will only fuel opposition to the military regime. Concessions to China on the Kyaukphyu project are therefore more likely.

Conclusion: What Lies Ahead?

The junta needs allies on the international front to provide diplomatic and economic support as well as meet its defense needs. While China will provide the Tatmadaw with some of this support, it is not the only country that can do so. The military’s active cultivation of other state powers in recent decades has put it in a far more comfortable situation than where it was in 1988. Given its continued suspicions of China, it is likely the junta will seek to keep its dependence on Beijing to a minimum.

Dr. Sudha Ramachandran is an independent researcher and journalist based in Bangalore, India. She has written extensively on South Asian peace and conflict, political and security issues for The Diplomat, Asia Times and Geopolitics.

Notes

[1] John G. Garver, Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century (New Delhi: Oxford, 2001), pp. 254-55).

[2] Zin, Min, “Burmese Attitude toward Chinese: Portrayal of the Chinese in Contemporary Cultural and Media Works,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 2012, no. 31, issue 1, p.115-131, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/186810341203100107.

[3] K. Yhome, “Understanding China’s Response to Ethnic Conflicts in Myanmar”, ORF Occasional Paper No. 188, April 2019, Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/understanding-chinas-response-to-ethnic-conflicts-in-myanmar-49759/

[4] Sudha Ramachandran, “Sino-Myanmar Relationship: Past Imperfect, Future Tense,” in China-South Asia Strategic Engagements, Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) Working Paper, August 23, 2012, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/media/isas_papers/ISAS%20Working%20Paper%20158%20-%20Sino%20Myanmar.pdf. See also Garver, n.1. pp. 263-66.