Cossacks Continue to be Rising Star in Kremlin Plans

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 22 Issue: 77

By:

Executive Summary:

- The Russian government is significantly boosting the visibility and funding of the Cossacks, as seen in budget increases, high-profile national gatherings, and cultural exhibitions linking them to the Soviet victory in World War II.

- The All-Russian Cossack Society has increased its media activity, reflecting a broader geographic scope and growing militarized initiatives such as youth training, Orthodox blessings, and deployment stories from a range of Russian regions.

- Victory Day 2025 marked intensified Kremlin efforts to unify registered and ethnic Cossack factions, aligning their historical narratives with current nationalistic goals and embedding them more deeply in Russia’s militarized civic culture.

The expansion of the Cossacks’ role in Russia, as implied by the doubling of their budget, appears to be well underway in 2025 (see EDM, November 27, 2024). Their touting as “the most powerful non-commercial social organization in Russia” as of June last year has been supported by numerous recent developments (VsKO, June 21, 2024). There has been an apparent effort to increase the organizational profile of the Cossacks, as evidenced by the consecutive Cossack “big circle” meetings held in Moscow. Considering that a total of only four “big [national] circle” meetings have been held since 1990, when the waning of Communist strength gave an opening for the “rebirth of the Cossacks,” this is a significant development (see EDM, April 17). Cossack rallies demonstrate a strengthening of the relationship between the state and the Cossacks. An exhibition on the author of the Cossack classic And Quiet Flows the Don opened in the venerated space of the Museum of [World War II] Victory, containing articles from the Soviet newspaper Red Star (Krasnaya Zvezda, Красная звезда) and Truth (Pravda, Правда) (VsKO, May 20). As recent events have made clear, the memory of the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War (what Russia calls World War II) remains the civic religion of the Russian state, and proximate events are blessed by association.

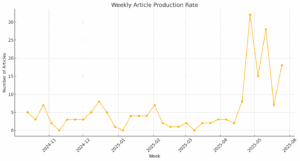

The article production rate of the All-Russian Cossack Society (Vserossiiskoye kazach’e obshchestvo (VsKO), Всероссийское казачье общество (ВсКО)) website appears to have increased significantly since Victory Day, on May 9. This is illustrated visually in Figure 1 below, which displays the production dates for articles by week. The website is the central coordinating mechanism of Russia’s registered Cossacks and regularly features articles regarding Cossack deployment. Previous evaluations of the website revealed an average of 351 articles produced annually between 2019 and 2023. (Numbers used from the corpus described in Richard Arnold & Alisa Neeman, 2025, “The Last Push from the South: Explaining the Spread of Russia’s Cossack Movement”, Problems of Post-Communism.)

Likewise, the geographical range of places covered by the articles has recently been much more expansive than before. One article reports on the attempts to create “a military-patriotic upbringing center” in the Republic of Kalmykia’s capital of Elista. The participants of the seminar were blessed by an Orthodox priest from the Kalmykia Cossack Cadets Corps and a local Buddhist Lama (VsKO, May 25). Another article focused on the departure of 30 replenishment soldiers from Orenburg for the Cossack BARS-6 battalion ‘Forshtadt’ (Форштадт), the Tsarist-era name for the fort that was located where Orenburg now stands (VsKO, May 22 [1]). There is an explicit appeal to memory politics involved in the very names of the units. So too with an article on Cossacks from Zabaykalsky Krai who are reported on as participating in military practice on one of the training grounds of the Eastern military district. The article claims that “204 Cossacks, including 47 representatives of the Cossack youth, performed exercises under the tutelage of experienced military instructors” (VsKO, May 22 [2]). Further, members from the Ussuri Cossacks host are featured in “training at the grounds of the 248th combined-arms training ground.” Specifically, those who participated in the training came from the Khabarovsk Krai, the Amur Oblast, and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. As in other articles, the important role for youth was emphasized (VsKO, May 22 [3]). Other articles include references to Chelyabinsk, Sakhalin, Krasnodar, Zaporizhzhia, Rostov, Moscow, and Stavropol. This contrasts with the geographic range of articles in 2024 and earlier, which was much more focused on Krasnodar, Rostov, and Stavropol (see Commentaries, May 21, 2021; see EDM, March 30, 2022, May 1, 2024). Although other places were mentioned, they were done so with less emphasis and frequency.

The May 9 Victory Day holiday also seems to mark a new high-water moment for Kremlin efforts to unite the ethnic and registered sides of the Cossack movement. Put simply, these two sides might be thought of as descendants of authentic Cossacks from the pre-Soviet times and modern “Asphalt Cossacks” who exemplify kitsch aspirants to some of the Cossack ideals and who have become alienated from the land that was traditionally the central concern of the Cossacks (see EDM, October 10, 2023, July 24, 2024). Recollections of leading registered Cossacks exemplify the role their ancestors played in the Great Patriotic War. An article on the VsKO website highlighted these ancestors. The article highlighted how the “grandfather of the Ataman of the all-Russian Cossack society, Nikolai Semovich, born on May 12, 1916, was ordered into the Soviet Army in 1937, and participated in the Finno-Soviet War [in 1939–1940]. He fought against the Nazi invaders from the first days of the Great Patriotic War … in the order of Bogdan Khmel’nitsky” and was awarded a medal. His brother also fought in the war (VsKO, May 8). Other Cossack leaders such as Alexander Vlasov (Kuban Cossacks), Igor Tsyganov (Orenburg Cossacks), Alexander Agibanov (Ussuri Cossacks), Sergei Boriadkov (Don Cossacks), Konstantin Daviatin (Volga Cossacks), Nikolai Chigov (Irkutsk Cossacks), Ivan Mironov (Central Cossacks), and Pavel Atramonov (Yenesei Cossacks) are also featured (VsKO, May 8). Similarly, many Cossack groups marched on Red Square in the Victory Day parade, uniting the registered and ethnic wings and claiming continuity between the events of the early 1940s and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine (see EDM, May 8; VsKO, May 9).

The Kremlin is consistently supporting efforts to increase the social presence and impact of the Cossacks in Russian life. This development will have enormous implications, regardless of how the war ends. The emphasis on the role of Cossacks in Russia’s war against Ukraine in Russian culture and the continued integration of Cossack culture in daily life will further contribute to the militarization of Russian society.