Pushback against Xi Jinping’s One-Upmanship Strengthens

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 7

By:

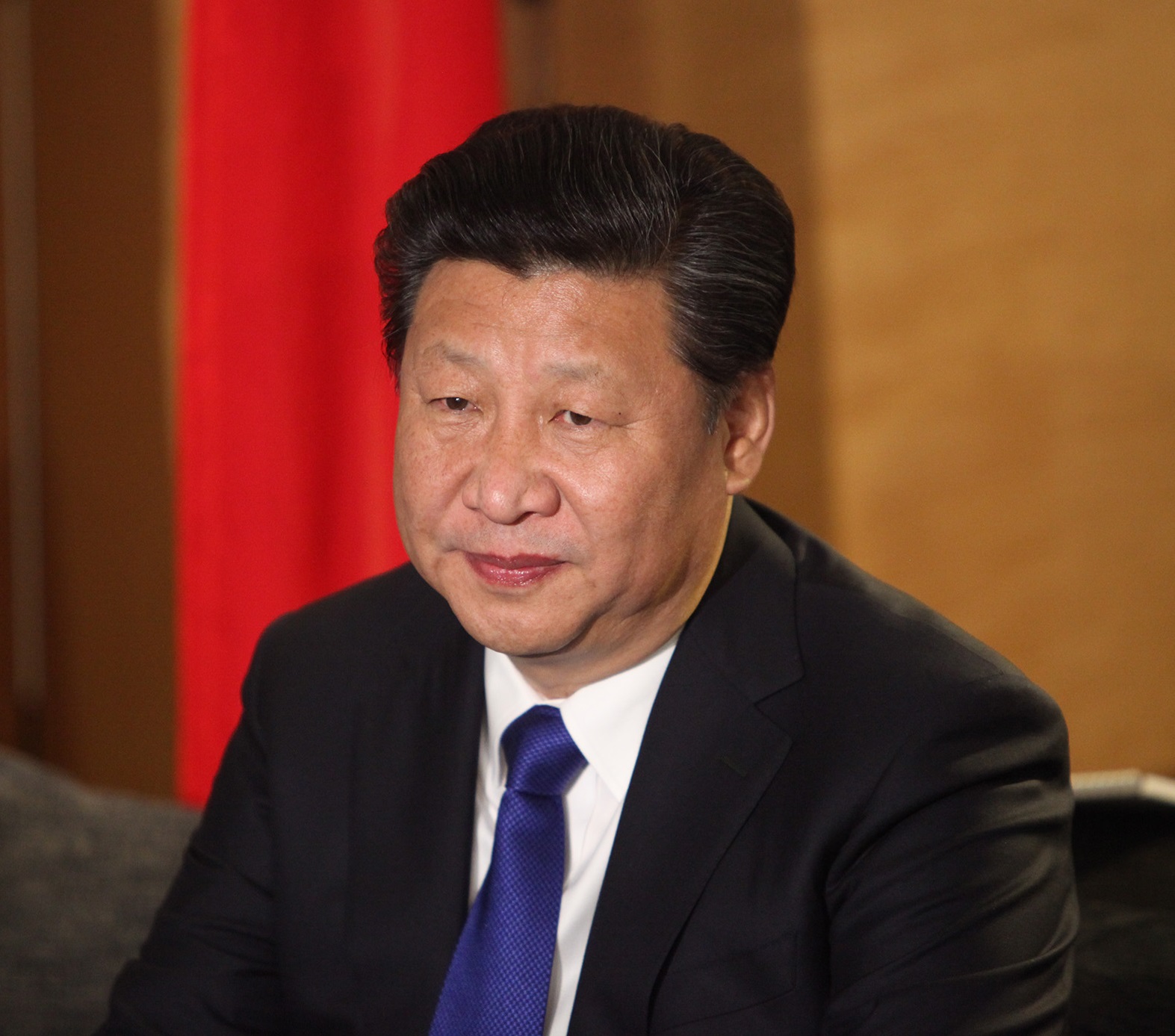

“Every bush and tree is an enemy” is a Chinese proverb that describes how the timid Emperor Fu Jian of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420 AD) was once so overawed by the superior troops of his opponent that he mistook nearby rows of neatly planted saplings to be soldiers. Chinese President Xi Jinping is no Emperor Fu Jian—he seems to be in full control of China’s military forces, the paramilitary police, the police and the spies—in addition to the labyrinthine Party-state apparatus. However, the Xi administration’s reaction to an anonymous letter calling for his resignation suggests that Xi, who is also Communist Party General Secretary and commander-in-chief, is far from secure about his powers.

On the eve of the National People’s Congress (NPC), which opened on March 5, Wujie News, an official website based in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR), carried “An Open Letter Demanding That Comrade Xi Jinping Resign From His Party and State Leadership Positions.” The article, which was signed by “a group of loyal party members,” was pulled from the site within an hour. The relatively obscure news site, which is controlled by the XUAR Propaganda Bureau, later said it was the victim of hacking by an unspecified party. However, the fact that the anti-Xi missive had first appeared on Caiyu.org, a New York-based pro-democracy media group, seems to suggest that the letter was the work of overseas-based critics of the Communist Party and particularly of Xi (VOA Chinese, March 28; United Daily News [Taipei], March 6; Canyu.org, March 4). [1]

Backlash

If Xi and his advisers had kept investigations low-key, the matter might not have dominated social media during the annual sessions of the NPC and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC)—and long afterwards. Under orders from security cadres including Politburo member in charge of the Central Political-Legal Commission Meng Jianzhu, police detained Wujie’s CEO Ouyang Hongliang, President Li Wanhui and about 15 other staff. It is likely that the website, which started operations only a year ago, will be closed down (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], March 24; RFI Chinese, March 24). More intriguing, however, was the arrest of popular columnist Jia Jia on March 15. Jia’s only involvement in the petition was that as one of the first readers of the Wujie article, he called up his good friend Ouyang to warn him of the consequences of the piece. Jia, who was released after being detained for ten days, is still under police surveillance (RFI Chinese, March 26; BBC Chinese, March 25; Apple Daily [Hong Kong], March 21).

Even more chilling, however, are Beijing’s efforts to harass and intimidate the relatives of foreign-based critics of the Xi administration. Take, for example, prominent blogger Wen Yunchao, who moved to the United States in 2012. Wen, who has 220,000 Twitter followers, is a frequent commentator on Xi’s ultra-conservative policies as well as opposition to Xi’s rule as manifested by the Wujie News letter. On March 22, Wen’s parents and brother, who live in Guangdong Province, were taken away by police. Several days earlier, the three were forced to make telephone calls to Wen asking him to reveal who the author of the anti-Xi petition was. Wen, who demanded that Guangdong police release his relatives immediately, said he had nothing to do with the incident (Amnesty International, March 25; Radio Free Asia, March 25). A similar fate befell Chang Ping, a famous journalist and regime critic who moved to Germany in 2012. After the publication of an article that blasted Beijing’s arrest of Jia Jia, two of Chang’s siblings were arrested late last month by police in his home province of Sichuan. Chang’s relatives were told they would be in trouble if Chang were to continue badmouthing the Xi administration in the Chinese language edition of Deutsche Welle and other foreign media (South China Morning Post [Hong Kong], March 28; HK01.com [Hong Kong], March 28).

Given that Xi and his publicists are feverishly constructing a Maoist-style personality cult around the supreme leader, it is easy to understand why the Wujie News event should have been taken seriously. Equally significant, however, is the fact that the Xi leadership’s supercharged reaction could betray lack of confidence. This feeling of insecurity could be prompted by strong signs of a pushback against Xi’s one-upmanship coming from power blocs in the Communist Party which have been marginalized or which are unhappy about the Fifth-Generation leader’s large-scale restitution of discredited Maoist norms.

One unmistakable signal that President Xi might no longer be having his way is that his status as “core of the leadership” is under challenge. In December of 2015, the official media began calling Xi the “core of the leadership.” And the leaders of at least 20 provinces and directly administered cities have professed allegiance to “the central party leadership with comrade Xi Jinping as the core” (See China Brief, March 7). However, during speeches in March given by NPC Chairman Zhang Dejiang, CPPCC chairman Yu Zhengsheng and Premier Li Keqiang—all of whom are members of the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC)—the word “core” did not appear. In his Government Work Report delivered on March 5, Li referred to Xi five times. For example, he praised the guidance provided by the “central party leadership with comrade Xi Jinping as General Secretary.” This wording was similar to the protocol accorded former president Hu Jintao, who never attained the status of “leadership core.” [By contrast, former president Jiang Zemin was called the “core of the Third-Generation leadership.”] This development shows there is still substantial resistance in the party to elevating Xi to the lofty status of “leadership core” (Hong Kong Economic Journal, March 10; Wen Wei Po [Hong Kong], March 6).

Tensions at the Top

At the same time, conflict between Xi and Premier Li—the representative of the rival Communist Youth League (CYL) faction headed by former president Hu Jintao—seems to have broken into the open. When Li finished reading the Government Work Report the morning of March 5, practically all the delegates present followed custom by giving him an enthusiastic applause. In the old days, former president Hu would shake hands with former premier Wen Jiabao. This time, however, Xi did not bother to clap his hands. There was zero communication that morning between Xi and Li, who were seated next to each other (Chinadigitaltimes.net, March 20; Ming Pao, March 15). It is hardly a secret in Beijing that Li resents the fact that despite the strong tradition of the premier being the final arbiter of economic policy, he has to subject himself to Xi’s guidance. Incongruities between Xi and Li on economic policy-making is said to be one reason behind faulty moves that have exacerbated crises associated with the stock market meltdown and the depreciation of the renminbi (South China Morning Post Chinese Edition, February 17; VOA Chinese, September 21, 2015).

Equally telling was Premier Li’s absence during a regular meeting of the Central Leading Group on Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (CLGCDR), which was a high-level decision-making body created by Xi in December 2013. It is chaired by Xi; and its three Vice-Chairmen are Li, PBSC member in charge of propaganda (and therefore most of Chinese state media) Liu Yunshan and Executive Vice-Premier and PBSC member Zhang Gaoli. Li did not show up during the CLGCDR’s 21st meeting held on March 22. The premier’s only previous absence from a CLGCDR conclave was on July 1, 2015, when he was on a European visit. This seems to confirm speculation that due to the friction between Xi and Li, the latter would probably only serve one term as premier. The possibility has increased that Li would move over to head the NPC after the 19th Party Congress in late 2017 (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], March 23; Xinhua, March 22).

Anti-Xi Faction Emerges

Moreover, the rivalry between PBSC members Liu Yunshan and Wang Qishan has also broken into the open. Liu, a protégé of former president Jiang Zemin, is in charge of the propaganda apparatus. Wang, a princeling (a reference to the offspring of party elders) and crony of Xi, heads the country’s Central Commission on Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI), the much-feared anti-corruption superagency. On the eve of the NPC, media controlled by Liu started attacking Ren Zhiqiang, a real-estate tycoon who is a popular commentator in the social media. Ren, a party member, was criticized for not following discipline by “making groundless criticism of the party leadership.” However, the website of the CCDI soon published a piece supporting party members who are sincere and forthright enough to offer constructive views about the party. It is well known that Ren is a close friend of Wang’s—and the propaganda machinery under Liu seemed to be targeting Ren so as to embarrass Wang (Theinitium.com [Hong Kong], March 2; Radio Free Asia, March 2; CCDI.gov.cn, March 1).

Apart from failing to nurture consensus and camaraderie within the PBSC, Xi’s hold over the so-called Gang of Princelings—which is considered a key power base of the president’s—seems to be less solid than before. Notable princelings have made both direct and indirect criticisms of Xi’s policies. According to Luo Yu, son of General Luo Ruiqing (1906–1978), who is a former Chief of the General Staff and vice-premier, an “anti-Xi faction” has emerged among cadres who thought the supreme leader “has not fully observed the Constitution and who are making no progress in reforms” (VOA Chinese, March 22). Zhong Shi, a columnist for Hong Kong’s Ming Pao, noted that while some princelings felt threatened by Xi’s anti-corruption moves, others who were businesspeople blamed their losses in the financial markets on the perceived failings of Xi’s economic policies. “Those princelings who still openly support Xi are those who have little influence and puny financial heft,” wrote Zhong (Ming Pao, March 22).

Conclusion

Zhang Lifan, an independent historian who is also the son of a minister, said Xi’s enemies were growing in numbers and ferocity because “he has moved everybody’s cheese.” Xi’s reinstatement of Maoist norms, including the reappearance of a cult of personality, said the historian, “has raised fears among people that Mao’s evil spirit has not dissipated and could make a comeback” (Canyu.org, March 22; VOA Chinese, March 21). Zhang, a well-known commentator, however, does not think that Xi is in imminent danger of losing power. “He is still the captain of a ship,” Zhang said. “While there are disgruntled interest groups on board, people are not yet ready to fire the captain for fear that sudden changes could result in a shipwreck.” What is certain, however, is that Xi is more feared than loved. And if his empire-building continues to make a dent on the welfare of disparate sectors in the polity, his enemies could coalesce and make his paranoia become reality.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department and the Program of Master’s in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including “Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping: Renaissance, Reform, or Retrogression?,” which is available for purchase now.

Note:

1. Another “dump Xi” letter, allegedly signed by “171 Chinese Communist Party members,” appeared in the bloggers’ section of the New-York based Mingjingnews.com site on March 29. He Pin, the owner of Mingjingnews.com, said he could not verify the identity of the letter writers, who called upon Xi to resign from all his positions. Since this letter did not appear in any media within China, however, Beijing has yet to make any reactions to this second anti-Xi petition (Apple Daily, March 30; Radio Free Asia, March 29).