Putin-Erdogan Meeting Shows Turkey Unfit to Mediate Between Russia and Ukraine (Part Two)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 140

By:

*Read Part One.

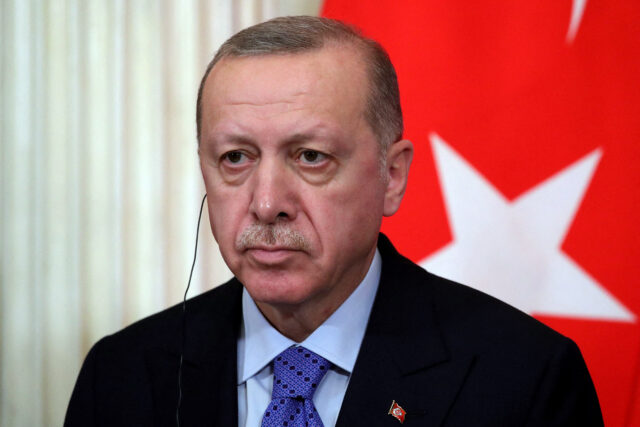

The Kremlin offered Turkey several major, highly attractive business projects at the bilateral summit in Sochi on September 4. These would further increase Turkey’s reliance on Russia in key economic sectors and on Russian-generated revenues (see Part One). By the same token, it casts doubt on Turkish President Recep Tayyp Erdogan’s ability to mediate between Russia and Ukraine in an even-handed or truly neutral manner.

Natural Gas Hub

During the two presidents’ meeting in Sochi, Russian Gazprom handed over the project roadmap for a natural gas hub in Turkey to Turkish counterpart Botas. Following the loss of the Nord Stream pipeline system in the Baltic Sea, the Kremlin proposes re-routing some of those gas supplies through the Black Sea and Turkey onward to Europe. Russian President Vladimir Putin first proposed this idea to Erdogan promptly upon the Nord Stream pipelines’ demise (Interfax, September 4).

Putin and other Russian officials further elaborated on this plan at the Sochi meeting. The project would involve Turkey re-exporting Russian and other gas volumes to European countries from a gas distribution center in Turkish Thrace, near the Bulgarian and Greek borders. The electronic trading platform attached to the distribution center would supposedly form prices for European consumers.

Turkey’s state-controlled Botas energy company signed gas supply and transit agreements with its Bulgarian and Hungarian counterparts earlier this year in January and August, respectively (Euractiv, January 4; Botas.gov.tr, August 22). Moscow and Ankara apparently expect to use Bulgarian, Serbian and Hungarian pipelines to connect the proposed Turkish gas hub with core European gas markets. Along with Russian gas volumes redirected from the Baltic route, the Turkish hub also accounts for Russian gas inputs from the South Stream and Blue Stream pipelines and lesser volumes from other supply sources.

The European Union intends to phase out imports of Russian oil and natural gas by 2027 (Euronews, July 6, 2022). Moscow apparently envisages the Turkish gas hub as an instrument to counteract Brussels’ policy. It wants Turkey to look complicit with Russia in derailing the EU’s goals, thereby compromising Ankara’s own agenda of rapprochement with Brussels.

Furthermore (and contradicting the logic of a hub’s trading platform), Russian and Turkish officials intend to switch from dollars to rubles in accounting for a growing share of Turkish payments for Russian gas supplies (TASS, September 5).

Moscow’s offer looks quite tempting to Turkish officials. But Turkey will need to start by modernizing its own gas market before the proposed hub can be a real possibility. The internal gas market is government-controlled, cartelized and incompatible with the hub project, according to Russian Energy Minister Nikolai Shulginov (TASS, September 5). As seasoned Turkish expert Necdet Pamir points out, a state-controlled internal gas market and a hub for the international gas trade cannot coexist in the same country (TASS, September 5). Turkey also suffers from a chronic deficit of gas storage capacity, which is a core component for a gas hub. Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar recognizes the need to expand storage capacities in response to Moscow’s proposal.

The hub proposal seems a long shot in practical terms and more politically than economically motivated from Russia’s perspective. It seems designed to tempt Ankara into aligning its policies more closely with Russia in the Black Sea and on European energy affairs.

Nuclear Power Plant

Russia’s state nuclear energy corporation, Rosatom, and its subsidiaries are building Turkey’s first nuclear power plant at Akkuyu (Mersin province) on credit. According to Rosatom President Sergei Likhachev, in reporting to Putin, the latest investment valuation stands at $23 to $24 billion, up from the previous $20 to $22 billion estimate (TASS, September 8). With full-fledged construction operations under way since 2018, the plant’s four power blocs are scheduled to start producing electricity in sequence between 2024 and 2027, or one per year. Putin and Erdogan, with their energy ministers, reviewed the current state of the project at their Sochi meeting. The Akkuyu plant is designed to produce 35 billion kilowatt-hours per year, equal to 10 percent of Turkey’s anticipated electricity demand.

Grain Processing Deal

The two presidents also agreed in Sochi that Russia would supply Turkey with 1 million tons of grain at a discounted price. Turkey’s milling industry would process that grain and deliver the product to certain African countries, either as flour or as bread. Moscow and Ankara claim to have agreed with Qatar to compensate Russia for the price discount granted to Turkey and to cover the costs of shipping to Africa. Erdogan suggested at the G20 summit in India that the full details have yet to be finalized. In this, the Turkish president implies that this should not be seen as a one-off arrangement, but a repeatable one (TASS, September 4, 12; Anadolu, September 4, 11).

This arrangement signifies Moscow’s compensation to Turkey’s milling industry for its loss of discounted Ukrainian grain volumes caused by Russia’s blockade of Ukraine. When the Black Sea Grain Initiative was in effect (July 2022–July 2023), Turkey had inserted itself as an intermediary to receive certain volumes of Ukrainian grain at discounted prices, process that grain in Turkey and then export the product. Some unofficial reports suggest that Russia rewarded Turkey similarly. These deals turned Turkey’s already massive milling industry into a top-ranked exporter. And it is one of the reasons behind Erdogan’s eagerness to reinstate the grain deal with its Russian-imposed parameters in the Black Sea.

According to Erdogan in Sochi, Russian-Turkish trade turnover almost doubled from $33 billion in 2021 to $62 billion in 2022. Western sanctions on Russia and their flouting by Turkey made this possible. Rounding out the picture, Turkey reportedly registered more than five million Russian tourist visits in 2022 and 2.2 million in the first half of 2023 (TASS, September 4). Erdogan’s stated target of $100 billion in annual trade turnover is a bit hyperbolic; nevertheless, trade will likely rise.

Overall, Erdogan and Turkish business interests have become heavily invested in economic and political relations with Russia. The extent to which this factor impinges on Turkey’s relations with the West is an open question. Ankara is almost certainly capable of balancing between the two sides in a transactional manner. But Turkey has clearly lost the ability to balance between Russia and Ukraine during the ongoing war; nor is it capable of holding the balance in the Black Sea vis-à-vis Russia (see Part One).

Turkey needs Russia much more than it needs Ukraine. At the same time, Ankara also has reasons to feel intimidated by Russia in the Black Sea. As such, Erdogan and Turkish diplomacy cannot act as even-handed, disinterested or truly neutral mediators between Russia and Ukraine. Erdogan’s mediation had some relevance in March and April 2022 when Ukraine was in dire military straits. Now, as Ukrainian forces have retaken the initiative on the battlefield, Kyiv’s Western allies can never allow such a situation to recur.