Russia in the Red Sea: The Search for Warm-Water Ports (Part One)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 139

By:

In recent days, waves of Russian drones have attacked the Ukrainian Port of Izmail, a major outlet for Ukraine’s grain exports (Al Jazeera, September 4). Such assaults on food infrastructure alarm the leadership of the drought-suffering parts of Africa that are reliant on Ukrainian grain. And as Russian President Vladimir Putin remains resistant to reviving the Black Sea Grain Initiative, this situation complicates the Kremlin’s efforts to expand influence on the resource-rich continent (see EDM, September 7).

Under the guidance of Putin, Moscow’s campaign throughout Africa pits Russian interests against those of the West. The long-term success of the Kremlin’s efforts will largely depend on the establishment of a secure Russian naval port, preferably on Africa’s Red Sea coast. But to create such a port, Russia must address its historical foreign policy failures on the continent.

When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, it created new strategic opportunities for the European powers. Great Britain, with an ambitious mercantile class supported by the world’s most powerful navy, took immediate steps to establish a chain of ports through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, allowing the wealth of its rich Asian dominions to flow freely to the empire’s center. France and Italy followed, establishing their own bases in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden to facilitate access to their colonies. Imperial Russia, a northern empire in a perpetual search for warm-water ports, was slow to see the opportunities presented by the canal. Thus, development in this direction was left to a group of privately backed Cossacks and Russian Orthodox priests to try to establish an African colony in Djibouti on the Gulf of Aden in 1889. This “New Moscow,” established on land already claimed by France, was quickly destroyed by a French naval bombardment.

The diplomatic crisis that followed sapped Russian enthusiasm for African adventures. By the time of the Russo-Japanese War, the significance of Russia’s failure to establish a Red Sea or Indian Ocean port was exposed when its Baltic fleet was forced to make an 18,000-mile voyage to the Sea of Japan without access to proper coaling and repair facilities. The lesson of the exhausted fleet’s destruction by the Japanese was understood by the Soviets, who focused on the establishment of warm-water ports to support naval operations in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Soviet Union’s collapse brought a temporary end to Russia’s presence overseas. But Putin’s neo-Soviet ambitions have revived the campaign to expand Russian military and commercial influence in Africa. Key to this is the establishment of a port on the strategically important Red Sea, the two most likely hosts being Sudan and Eritrea, nations that are similarly at odds with the West.

Khartoum was engaged in talks with Moscow over the establishment of a Russian naval base on Sudanese territory up to the outbreak of clashes between rival wings of the Sudanese military in April 2023 (Africanews, March 3, 2022; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, February 11; TVP World, February 18; see Terrorism Monitor, April 28). Now, due to the ongoing turmoil within the country, Moscow’s focus has shifted to Eritrea, a stable but totalitarian state accused of significant human rights violations and crimes against humanity.

Eritrea is currently ruled by 77-year-old President Isaias Afwerki and has not held an election since achieving independence in 1993. In terms of both prosperity and civil freedoms, the country ranks near the bottom in both categories; many citizens are reliant on remittances from Eritrean expatriates to obtain basic necessities (Africanews, May 23). Many expats have fled Eritrea to escape mandatory conscription for indefinite periods and other hardships. Even so, the regime’s agents abroad continue to try to control their lives through taxation, threats to family members and other measures.

In the early years of independence, Eritrea enjoyed a congenial relationship with the United States. However, tensions arising from the 1998–2000 border war with Ethiopia led to a rift with Washington and a shift away from democratic norms and regional cooperation in favor of xenophobic sentiments. All economic failings of the regime are attributed to United Nations and United States sanctions, promoting anti-Americanism in a country with little access to independent news sources (Press.un.org, December 23, 2009; State.gov, November 7, 2022). Eritrea is thus viewed in Washington as a destabilizing influence in the Horn of Africa and a possible partner of both Russia and Iran. Moscow favors removing the UN sanctions on Eritrea; however, doing so will require the support of nine members of the Security Council, including all five permanent members (TASS, August 31, 2018).

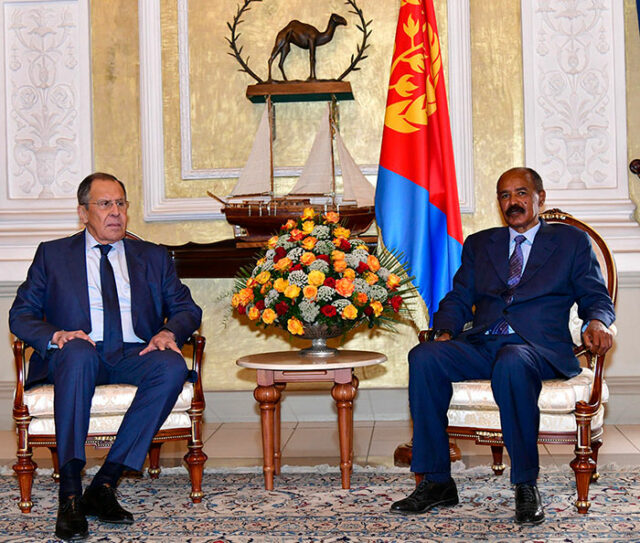

Eritrea has repaid this diplomatic support by being one of only five countries to vote against the March 2022 UN resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. During a visit in January 2023 by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, his Eritrean counterpart, Osman Saleh, blamed the war in Ukraine on America’s “reckless policy of hegemony and containment that they have pursued in the past decades” (Shabait.com, January 27).

Indeed, Eritrea’s relations with Russia have intensified of late. Having never made a trip to Moscow since independence, Afwerki has already made two this year (Kremlin.ru, May 31). A major topic of discussion has been the establishment of Russian naval facilities on Eritrea’s 700-mile Red Sea coast. The prime candidates for such facilities are the ports of Assab and Massawa. During a July 28 meeting with Putin on the sidelines of the second Russia-Africa Summit, Afwerki described Russia’s war in Ukraine as resistance to a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) plot to rule the world: “The war declared by NATO on Russia is not only against Russia; its aim is to dominate the whole world. … NATO is defunct. NATO does not exist. NATO is in intensive care. … I think we need to strategize, and I say Russia will have to lead this strategy. Russia will have to design a plan on facing this declared war, not only on Russia, but this is a global war. Everybody should come and join Russia in this strategy, and the sooner, the better” (Kremlin.ru, July 28).

Such enthusiasm for Russian leadership was in short supply at this year’s Russia-Africa Summit. Attendance logs show a significant drop-off in African heads of state: from the 43 who attended the first summit in 2019, only 17 did so this year (see EDM, July 31). The summit came ten days after Russia announced it was pulling out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative. And Putin’s pledge to ship limited amounts of free grain to six friendly African nations, including Eritrea, did little to appease those states not on the list.

Thus, the contradictions between Moscow’s policy in the Black Sea and its ambitions in Africa were exposed just as Russia’s influence offensive in Africa has been ratcheting up (see EDM, June 6, September 6, 8). To move forward with its plans in the Red Sea, Moscow will need to emphasize a Russian option to the alleged threat from the West on the sovereignty of non-democratic states like Sudan and Eritrea.