Russia’s ‘Pivot’ to China Is Reduced to High-Level Bonhomie

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 115

By:

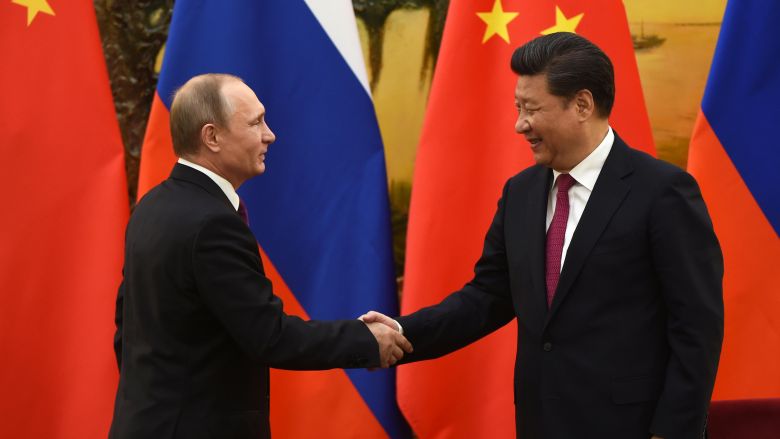

Expectations regarding President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Beijing on Saturday (June 25) had been rather subdued, and the modest results were mostly immaterial. Last year, the two leaders grandiosely celebrated their countries’ World War II victory over the Axis powers; and in 2014, they announced a great increase in economic ties and an allegedly historic natural gas deal (see EDM, May 22, 2014). But the implementation of this deal has been delayed, and the volume of bilateral trade—instead of the promised fast expansion—has contracted by about 30 percent. Thus, Putin’s argument that the Russia-China relationship should be redefined from a “strategic partnership” to a “comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation” rings diplomatically hollow (Kremlin.ru, June 23). In fact, the only element of the partnership that works well for Putin is his personal connection with President Xi Jinping (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 24). Chinese commentators also emphasize the demonstrative friendliness of this high-level networking (RIA Novosti, June 24).

Nevertheless, none of the Chinese leadership chose to attend last week’s St. Petersburg Economic Forum, despite Russian efforts to profile this annual event as the best opportunity for investors to obtain access to key policymakers. Russia’s conflict-distorted relations with Europe were, indeed, the main theme of discussions this year. Putin held lengthy meetings with former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and Jean-Claude Junker, the President of the European Commission (RBC, June 17). No compromise on the sanctions regime was found, but Putin now expects that the shocking outcome of the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom will inflict massive damage on the European Union’s capacity for decision-making (Ezhednevny Zhurnal, June 24). His neutral statements about bad and good consequences of the Brexit can barely hide his gloating, but this attitude stands in sharp contrast with the deep concerns in China (RBC, June 24). Beijing much prefers to have a stable economic partner in the EU and eschews any external shocks that could add to the fragility of its own economic system (RIA Novosti, June 17).

The Russian president is not comfortable with his country’s growing economic dependence upon China and seeks to diversify, but his meeting, in May 2016, with the leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was far from fruitful (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 3). He is also trying to explore opportunities with Japan, and Prime Minister Shinzō Abe is eager to proceed with a “new approach” that could deliver a breakthrough in the long-deadlocked bilateral dispute over the southern Kurile islands (Novaya Gazeta, June 24; see EDM, January 13). It is difficult, however, to combine this diplomatic maneuvering with Russia’s modernization of military infrastructure in the Far East and on the Kurile Islands, which is supposed to increase Moscow’s ability to conduct muscular policy in the Asia-Pacific (Gazeta.ru, May 27). Japan was appalled, for that matter, with the simultaneous appearance of Russian and Chinese combat ships near the disputed Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands, which most probably was a coincidence carefully orchestrated by the Chinese Navy (Newsru.com, June 9).

On the way to Beijing, Putin made a stop in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) held a summit to mark its 15th anniversary (Kommersant, June 24). China seeks to turn this underachieving institution into a conduit for executing its Silk Road Economic Belt initiative in Central Asia. Russia pretends that it has no problem with this expansion, but is, in fact, quite content with the organization’s mediocre success (Vedomosti, June 15). The SCO has no experience in dealing with acute security challenges, like the terrorist attack in Aktobe, Kazakhstan, earlier this month (Slon.ru, June 9; see EDM, June 21). Its main success story has been enlargement: India and Pakistan have been accepted as full members, with Iran presumably next in line (Moskovsky Komsomolets, June 24). It is hard to expect, however, that by adding to its area of nominal responsibility, the organization will gain in effectiveness; and Moscow appears perfectly satisfied with this prevalence of photo-ops over substance.

What member states in the SCO, as well as in the ASEAN, are primarily interested in discussing is economic growth, but Russia has little to say on the subject. Every time Putin declares the Russian economy has found a “bottom” in the crisis, another contraction invariably follows (Kommersant, June 23). Chinese investors have lost confidence in Putin’s promises and are perfectly aware of the jumble of bureaucratic red tape in the Russian economy (Forbes.ru, June 20; Kommersant, May 31). The joint projects that are moving forward often involve a transfer to Russia of dirty industrial enterprises from China (see EDM, April 28), like for instance aluminium production to Krasnoyarsk, which is already suffering from a near-catastrophic ecologic situation (Novaya Gazeta, June 22).

The Chinese leadership well understands the setbacks to advancing the important bilateral partnership and so puts greater emphasis on the element that appears to be working—personal ties between Xi and Putin. The decision to rescue Russia’s Yamal-SPG gas project with generous Chinese loans amounting to $12 billion and to take some 30 percent of the shares in its operator Novatek was driven not by commercial interests but by political assumptions about the importance of this project to Putin (Kommersant, June 3). Putin, meanwhile, is eager to confirm that Russia’s positions on key international issues are close to the Chinese, and he promises to fully support Beijing in organizing the G20 summit in Hangzhou, China, this September (RIA Novosti, June 25). This bonhomie stands in sharp contrast with the change in Russian public opinion: only 34 percent of Russians now see China as a key ally, compared with 43 percent in 2015 and 40 percent in 2014 (Levada.ru, June 2).

In essence, Russia continues to be a western-oriented country, and the “hybrid war” with Ukraine has, paradoxically, made it even more Euro-centric. The Russian-European conflict over values, political freedoms and human rights has certainly reached extreme intensity, but the concentration of political efforts and public attention has also increased. Putin may enjoy the red carpet treatment in Beijing, but he cannot connect with the Chinese political culture, including its severe clampdown on corruption; and there is hardly any real trust between him and Xi. Putin’s overlapping circles of courtiers, siloviki (security services personnel) and oligarchs have no illusions that China would come to Russia’s rescue in the deepening crisis, and their main game plans involve manipulations of various European assets. The China “card” is not particularly useful in these games, largely because the Chinese are resolutely not playing along.