Chinese PSCs: Achievements, Prospects, and Future Endeavors

By:

Executive Summary

- Along with their clear internal (domestic) needs, Chinese private security companies (PSCs) have been spotted operating in virtually all major regions around the world. These entities currently play a marginal role in the promotion and protection of Chinese interests abroad, though they will likely grow in importance over the next ten years. Their impact, nevertheless, will presumably be far less visible than other tools used by Beijing, such as building business and trade ties and cooperating with partners’ defense ministries.

- Among the regions where Chinese PSCs have developed a presence, Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa stand out as top priorities to Beijing, with the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia quickly becoming more relevant.

- The Chinese Communist Party is reluctant to introduce legislative changes and empower PSCs, severely limiting these entities’ level of expertise and operational capacity. The majority of Chinese PSCs operating abroad are unable to perform sophisticated security missions in complex security environment. Chinese security providers generally perform either basic security services (e.g., bodyguards for high-profile individuals), or they work closely with local security bodies and law enforcement agencies.

- Despite Beijing’s deep and comprehensive involvement, many of China’s partners are strongly opposed to the deployment and presence of Chinese PSCs on their territories on a permanent basis. These countries view such a scenario as a partial forfeiture of sovereignty. The risk of souring China’s image as a responsible player primarily interested in forging economic and business ties may cause Beijing to resist the “overuse” of PSCs in certain regions.

The decade of “geopolitical shocks,” starting with Russia`s illegal annexation of Crimea that ultimately led to Russia`s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to the conflicts in the South Caucasus and continuation of civil wars in Libya and Syria, has had a profound security impact on wider Eurasia. These developments have created a series of additional challenges to China`s ambitious plans within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). To protect its assets and Chinese nationals working along the BRI, Beijing is searching for comprehensive solutions that would be more effective in this regard while trying not to alienate local stakeholders. Beijing has considered the increased use of private security companies (PSCs) as one possible solution.

The papers in the project “Guardians of the Belt and Road: The Role of Private Security Companies (PSCs) In Securing China’s Overseas Interests”[1] explored the architecture and various activities of Chinese PSCs in strategically essential regions that are plagued by instability and multiple security risks. From a geographic point of view, the papers discussed the activities of Chinese PSCs in Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

As the final part of the project, this paper provides a summary of the activities—both real and prospective—of Chinese PSCs in the aforementioned regions as well as their achievements and operational tasks. It also discusses the implications for the United States and its regional allies and partners resulting from the growing activities of Chinese PSCs in specific regions. Special emphasis was given to collecting primary source data for this paper, with some secondary literature selected for background. Interviews were conducted with the following subject matter experts specializing in the selected regions: Adina Masalbekova, independent researcher from Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan[2]; Leland Lazarus, associate director of National Security at the Florida International University Jack Gordon Institute for Public Policy[3]; Evan Ellis, Latin America research professor with the US Army War College[4]; and Kiyya Baloch, an independent analyst tracking the insurgency of Islamic radicals in the country and following the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

The paper starts by providing a summary of activities of Chinese PSCs in Central Asia. It then analyzes the activities of these entities in Africa – paying special attention to the Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone countries. Subsequently, the most recent developments in South Asia (and more specifically, the case of Pakistan) will be scrutinized. After taking a closer look at the activities of Chinese PSCs in the MENA region, the paper will offer conclusions and suggest areas for further investigation.

Regional Activities of Chinese PSCs: Main Takeaways

Central Asia

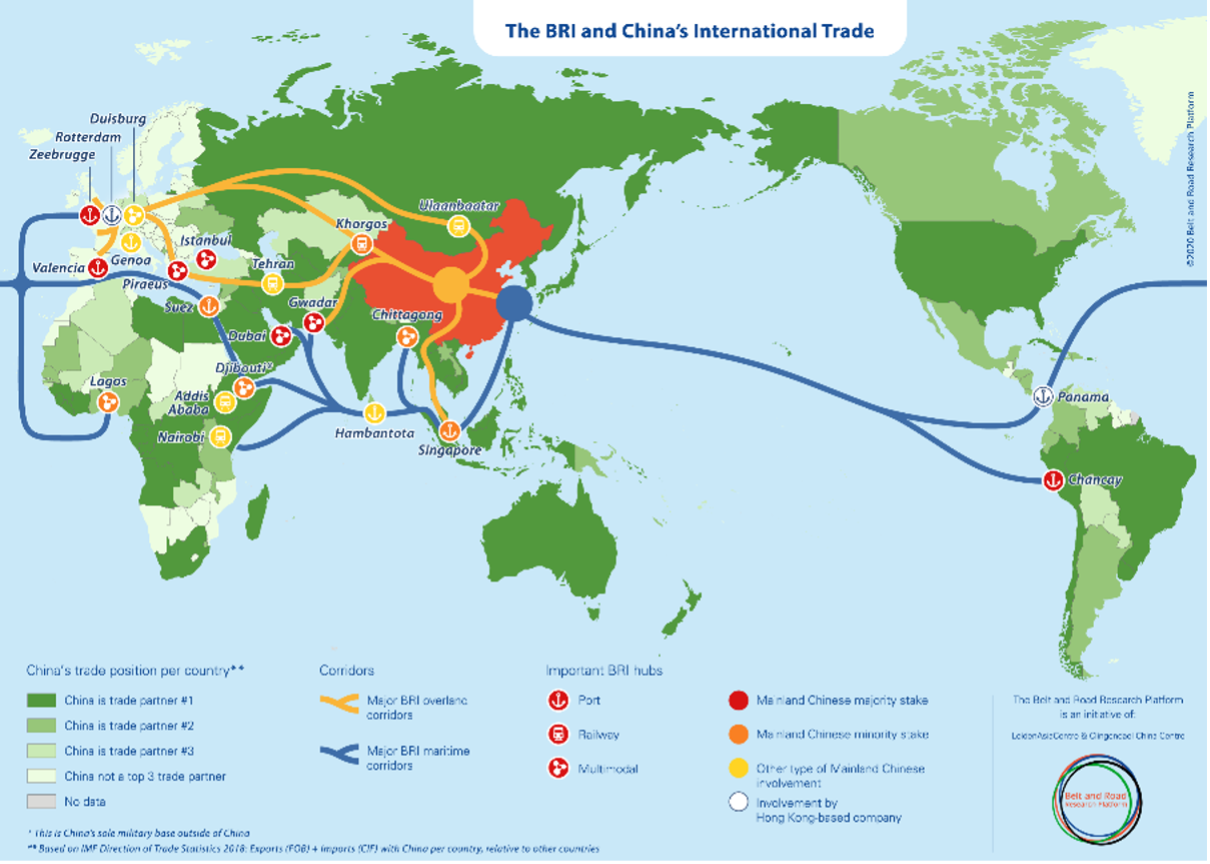

Being so geographically close to China, Central Asia[5] is a vital region to Beijing for three primary reasons. First, China can glean great geo-economic benefits from the region as reflected in its strategic natural resources. Central Asia also has the potential to provide critical logistical and transportation links within China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), opening up key trade corridors (see below). The trade routes most important to Beijing include the New Eurasian Land Bridge (NELB), China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor (CCAWAEC), and China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The strategic importance of these routes is highlighted by the fact that they serve as the only direct land-based routes from China to European consumers. The use of these corridors is heavily dependent on the security situation in Central Asia and Afghanistan.[6]

Source: Clingendael

Second, China is concerned that conflicts in Central Asia may threaten domestic security.[7] The growing threats of terrorism, extremism, and regional instability due to Soviet-era disagreements over water and territory undergird Beijing’s worries. China’s security concerns in Central Asia follow the so-called “Three Evils” (or “Three Forces”; 三股势力)—terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism.[8] Third, stability in Central Asia is key to Beijing in achieving its stated geopolitical goals. The Chinese strategic formula seeks to “stabilize in the east, gather strength in the north, descend to the south, and advance to the west” (东稳, 北强, 南下, 西进).[9] This outlook considers Central Asia to be an important strategic theater for advancing this agenda.

Beijing’s involvement in the region is distinct in its complexity and sophistication. It is premised on four pillars: military presence, the trade and import of natural resources, investment, and the use of “soft power” tools.[10] Given the complex security environment, China has employed various means to protect its assets, including Chinese PSCs in certain situations. Based on the results of this project, in Central Asia, Chinese PSCs have been primarily employed in Kyrgyzstan, albeit in a clandestine manner.[11] These entities have primarily provided basic security functions (e.g., physical protection of critical infrastructure and mining facilities). For now, only one entity, Zhongjun Junhong (中军军弘保安服务有限公司), has become clearly established in the region. Experts have noted that the prospective emergence of Chinese PSCs in the other countries of the region on a permanent basis over the next eight to ten years is not high. This is based on an analysis of country-specific security considerations and public sentiments.

Chinese security personnel have their strongest regional presence in Kyrgyzstan. The situation, however, is more complex than it might appear on the surface. According to Adina Masalbekova, “The activities of Chinese PSCs in Kyrgyzstan remain very low-key due to prevailing anti-Chinese sentiments among the public.” The security functions are rather basic. They generally take the form of “joint cooperation with Kyrgyz local security organizations providing some instructions and technical equipment for security purposes.” Masalbekova continues:

Given their invisibility, it is hard to evaluate their performance directly. However, some social media activists shared incidents of receiving threats online and via calls from unknown groups after being vocal about issues at Chinese-led factories and mining plants. Government officials carefully approach the issues related to Chinese companies operating in the country, mentioning that China is a big creditor and economic partner. While the above-mentioned cannot be a result of Chinese PSCs’ performance, this can be perceived as a more positive turn for Kyrgyzstan-based Chinese companies compared to the strikes and protests against Chinese investments before.

The Kyrgyzstani government has cooperated with China on certain security matters. Yet, Moscow’s continued partnership with Bishkek on some matters has limited that cooperation. As Masalbekova stated,

The current [Kyrgyzstani] regime has been proactively supporting and increasing cooperation mechanisms with China, as well as adopting some of its surveillance practices. However, whether there will be any drastic changes in the use of Chinese PSCs over the long term depends on many factors, including the outcome of the war in Ukraine. … Russian influence in Kyrgyzstan and in [Central Asia] remains … demonstrated by the prosecution and extradition of Russian anti-war activists.

The most realistic scenario for increasing the activities of Chinese PSCs in Kyrgyzstan involves the construction of the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan (CKU) railway. Masalbekova stipulates that this project “will most likely increase the involvement of PSCs under security cooperation mechanisms, with the aim of fighting destabilization as China invests substantially in the region with a potential threat to affect stability within China itself.” She argues that “supporting authoritarian rule in Central Asia better serves Chinese interests in the region” and will likely have an impact on the activities of PSCs as instruments of Beijing’s power projection.

In Kazakhstan, public opinion is strongly against any foreign security presence in the country. As such, Beijing would like to avoid exerting pressure on local authorities and making overt calls for the deployment of PSCs in Kazakhstan. China is primarily relying on trade and business ties as well as other soft power tools in dealing with Astana. As a result, Beijing steers clear of engaging in rhetoric that may tarnish its image. Bilateral security cooperation will thus continue through the official lines of contact between the two countries’ respective defense ministries for the foreseeable future.

In Uzbekistan, the deployment of Chinese PSCs has been limited. The country has arguably the most developed security apparatus and armed forces in Central Asia. At least one PSC, the China Security Technology Group (中国安保技术集团), claims to provide security services in Uzbekistan,[12] though their exact nature is unknown. Such services were reportedly provided at a basic level, as China Security Technology Group does not have an official branch in Uzbekistan. Similar to Kazakhstan, cooperation between China and Uzbekistan on security and defense matters will likely be maintained through official channels.

In Tajikistan, the prospective emergence of Chinese PSCs is quite high due to the country’s economic dependency on China. The country has possibly the least stable security environment in the region due to, among other factors, the reoccurring border conflict with Kyrgyzstan. Based on this project’s findings, however, a dramatic increase in the presence of Chinese PSCs in Tajikistan over the short time is rather low. There is little evidence to indicate that Chinese PSCs are currently operating in Tajikistan. Nevertheless, an analysis of the Chinese PSC industry points to China Overseas Security Group (中国海外保安集团) and Frontier Services Group (先丰服务集团) as the enterprises best suited for deployment.[13]

In Turkmenistan, China’s approach to defense and security issues has been incremental and plays a secondary role to the development of economic and business ties. The country was not considered an integral part of the BRI until quite recently, yet its importance seems bound to grow.[14] Currently, there is no evidence of Chinese PSCs operating in Turkmenistan.

One major factor that will inhibit China’s reliance on PSCs in Central Asia (at least in the next eight to ten years) is the hanging specter of the Wagner Group.[15] Its crimes in Ukraine, Syria, and Sub-Saharan Africa (as well as its recent attempted mutiny inside Russia[16]) have hurt the overall legitimacy of paramilitary organizations in providing permanent security services. China’s determination to avoid hurting its image in Central Asia as a business-oriented partner may keep it from turning to PSCs as extensive tools in its influence efforts.

Key impediments remain to Beijing’s increased reliance on PSCs in Central Asia to secure its interests and assets, at least in the short term. The United States must keep a sharp eye on this activity so as not to lose out to China in the region. Speaking on the implications of expanded Chinese involvement in Central Asia through PSCs, Masalbekova explicitly stated,

There certainly should be concerns for the US in responding to the activities of Chinese PSCs in Central Asia, especially as the CKU railway project has been taken to a new level. … Emphasis on cooperation with the Central Asian region was marked at the SCO [Shanghai Cooperation Organization] in Samarkand in 2022 and the Xi’an summit in 2023. For a region with the need for infrastructure development, the actual implementation of railway projects might only increase the compromising economic and political ties with China. … The current regime may use these ties to increase the presence of Chinese PSCs to export their methods of approaching ‘security-related’ issues: training programs and the provision of Chinese technology and equipment (e.g., surveillance cameras and telecommunication infrastructure). Considering the suppression of freedom of speech in Central Asia … the potential increase of Chinese PSCs might directly or indirectly affect the reports on issues related to Chinese funds linked to the CKU railway and other projects. … There is still an underestimated but important aspect of influence coming from Russia and used by the Chinese side, which is to demonize US initiatives in the region as some kind of destructive force. In this regard, the US approach should be more carefully considered.

That said, while the presence of Chinese PSCs in some areas of Central Asia has been documented, experts do not believe that the large-scale emergence of these entities should be expected over the next several years. Some experts are still concerned that the overarching dependence of the Central Asian states on China might make local political elites more docile to Chinese efforts in building up its security presence on their territories.

Chinese PSCs in Africa: The Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone Countries

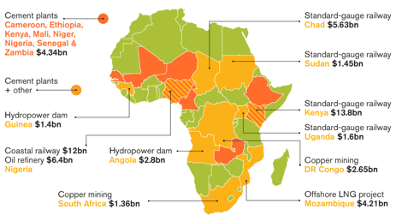

Sub-Saharan Africa is critical to Chinese interests from an economic perspective. In addition to vast natural resources—such as rare earth minerals that are indispensable for China’s industrial sector—Africa is emerging as a new market for Chinese goods and services and looks attractive for outsourcing labor. The continent is home to some of the most rapidly growing and youngest populations in the world. Overall, Africans, especially the younger generations, maintain a generally positive attitude toward China and welcome projects linked to the BRI at the governmental and grassroots levels. Some of China’s most well-known and notable projects in Africa were covered within the scope of this project in the paper, “Chinese PSCs in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Anglophone Africa.”[17] Some of those are pictured in the figure below.

Source: International Institute for Environment and Development

Beijing’s efforts to expand its economic presence in Sub-Saharan Africa is confronted by three major obstacles:

- Sinophobia and anti-Chinese protests in some countries hurt Chinese efforts. These sentiments stem from China’s handling of the exploration for natural resources, which has involved instances of racism and exploitation of local workers.

- Radicalism and terrorism are rapidly spreading across Sub-Saharan Africa in general and in resource-endowed regions—those strategically important to Chinese investors—in particular, which frequently bear the traits of Sinophobia.

- Kidnappings for ransom[18] specifically target Chinese nationals working in Sub-Saharan Africa under the conviction that Chinese companies are cash-rich and can meet the demands of kidnappers.

Beijing has employed a number of strategies to better protect its nationals and material assets in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Chinese side has cooperated with peacekeeping missions in the region, become better integrated in the African security environment via collaboration with major regional security organizations, engaged in arms sales, and assisted with military training and education.

Chinese PSCs are also operating on the continent. The research for this project on Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone countries in Sub-Saharan Africa identified the following PSCs that are active in the region:

- Hua Xin Zhong An (HXZA; 华信中安集团);

- Frontier Services Group (FSG; 先丰服务集团);

- Overseas Security Guardians (OSG; 中军军弘保安服务有限公司), established by the ZhongJun JunHong Group;

- DeWe Security Service Group/Dulwich International Security Group (DeWe; 德威国际安保集团)

- China Security Technology Group (CSTG; 中国安保技术集团有限公司)

Based on these results, one could argue that Sub-Saharan Africa represents the region with the greatest involvement of Chinese PSCs. Even so, two key factors curtail their activities. First, while public opinion is supportive of China in general, it is strongly against foreign PMCs and PSCs being deployed on African soil. This likely stems from the historical trauma of the decolonization period and fear of repeating the fate of Syria, the Central African Republic (CAR), and other pariah states with an extensive presence of foreign paramilitary personnel—the Wagner Group in particular. China is extremely cautious with its image and does not want to alienate African countries, especially in countries where Beijing has had success its advancing business and trade ties.

Second, for now, Chinese PSCs are clearly not ready to solve a wide spectrum of security-related issues in the complex environments of countries such as Mozambique, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the CAR, and the Sahel countries. Given their structural weaknesses, these entities struggle to provide services that go beyond basic security functions. Even much more capable forces—such as the battle-hardened Wagner Group—have not succeeded in major security endeavors. Keenly aware of this, Beijing is likely to maintain official military contacts with local authorities and, when it does employ PSCs, work with local operators to become more familiar with localized security problems.

It would be fair to assume that, in the next eight to ten years, PSCs are unlikely to play a critical role in protecting China’s strategic interests in Africa.

South Asia: The Case of Pakistan

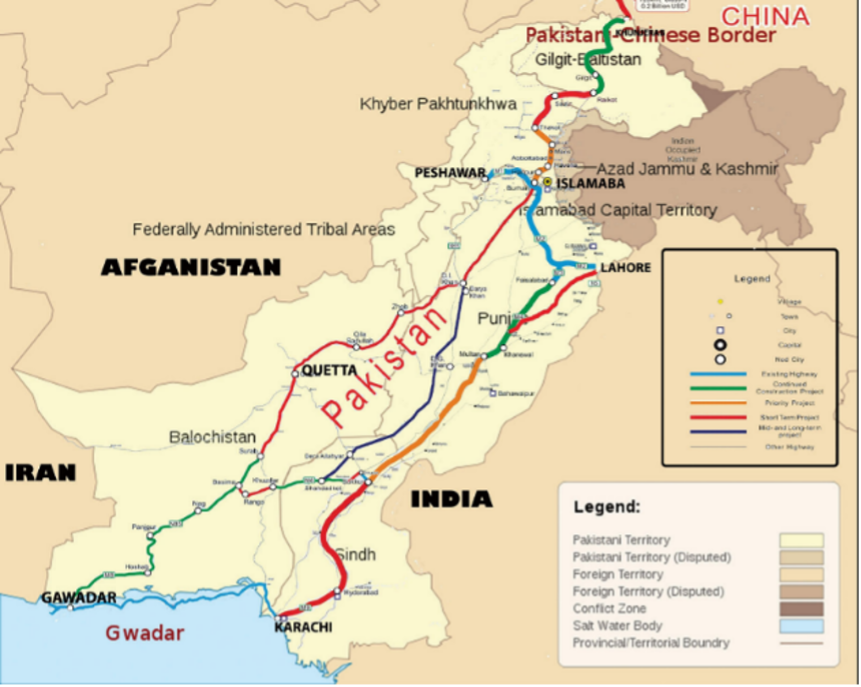

South Asia is bound to play a key role in China’s BRI. Pakistan, by the virtue of its geographic position and strong security, economic, and political ties with China, is well-positioned to capitalize on these prospects. Beijing is looking to expand its cooperation with Islamabad and has used the designation “all-weather friendship” (全天候友谊)[19] to define their bilateral relationship. Unlike Central Asia, China is strategically interested in Pakistan due to both land- and sea-based facilities critical for the development of Chinese trade and transportation routes. This is best visible in the figure below displaying Pakistan and some of the most important transportation arteries to Beijing.

Source: The China Story

That said, China’s ambitious plans in the region are facing serious challenges—namely, the spread of violence and increasing terrorist threats. These trends pose multiple risks to Chinese nationals and material assets deployed in South Asia in general and Pakistan in particular. Islamic radicals operating in parts of Pakistan are determined to specifically target Chinese nationals and derail Chinese-led infrastructure projects.

In response, China has strengthened its security partnership with the Pakistani authorities. Yet, this has done little to significantly improve the security situation. Incidents of violence against Chinese nationals in Pakistan have been on the rise. It appears that local officials find it rather difficult to effectively protect Chinese workers and personnel.[20] In recent months, Beijing has appealed to Islamabad to allow Chinese private security personnel to be deployed in the country to facilitate effective protection of Chinese nationals.

Islamabad has thus far brushed off these requests. Analysis of secondary data and interviews conducted with leading Pakistani security experts confirmed the unwillingness of the Pakistani government to permit the permanent deployment of Chinese PSCs in the country. Such an arrangement would be construed as at least a partial forfeiture of sovereignty and represent a public admission of the government’s inability to maintain stability.

As of now, several Chinese PSCs have been spotted operating on Pakistani soil. Yet, two aspects considerably constrain their actions. First, Chinese operators are not allowed to act independently or without the Pakistani authorities monitoring their activities. Second, Chinese PSCs do not enjoy permanent representation in Pakistan, which considerably curtails their ability to carry out more sophisticated operations.

Beijing is aware that the deployment of its security personnel in Pakistan could enflame anti-Chinese sentiments across the county, particularly in Balochistan, where Baloch militants describe Beijing as an “occupier.” China may be willing to allow the security situation in Pakistan to deteriorate further to drive home the point that Chinese PSCs are a necessity in adequately protecting Chinese nationals.[21] According to Kiyya Baloch, China’s prospects regarding the expanded use of PSCs in Pakistan are constrained by the fact that local residents “view China as a colonizer and exploiter due to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor’s resource exploitation. Introducing Chinese security companies … would only fuel Balochistan’s resentment toward China, potentially escalating the situation further.” He doubts that a large number of Chinese PSCs “will come to Pakistan soon, despite pressure from China to allow their PSCs to protect their projects. … Pakistani security personnel and agencies prefer handling regional security challenges themselves to avoid conflicts between China and locals.”

Even so, the United States needs to keep a better eye on the possibility of Chinese PSCs proliferating in South Asia. On whether the United States should respond to the prospective activities of China in the region, Baloch stated,

If Chinese investment plays a vital role in peacebuilding and economic stability, the United States should encourage such constructive engagement, particularly in Afghanistan. However, the United States must also be vigilant and firm if China’s actions jeopardize democratic institutions, peace, prosperity, and emerging democracy in countries like Pakistan, a crucial American ally. Monitoring Pakistan’s economy, security, and powerful army is essential to ensure they do not undermine the US role in Pakistan. Engaging with stakeholders in the region … through cultural and educational activities is vital for the United States to maintain its presence and promote democratic values in the region.

The emergence of Chinese PSCs on Pakistani soil on a permanent basis, though not entirely unrealistic, is unlikely to occur over the next several years. In addition to a clear lack of desire on the Pakistani side, Chinese PSCs are unlikely to be able to comprehensively solve the security-related challenges faced by the Chinese nationals.

Latin America and the Caribbean

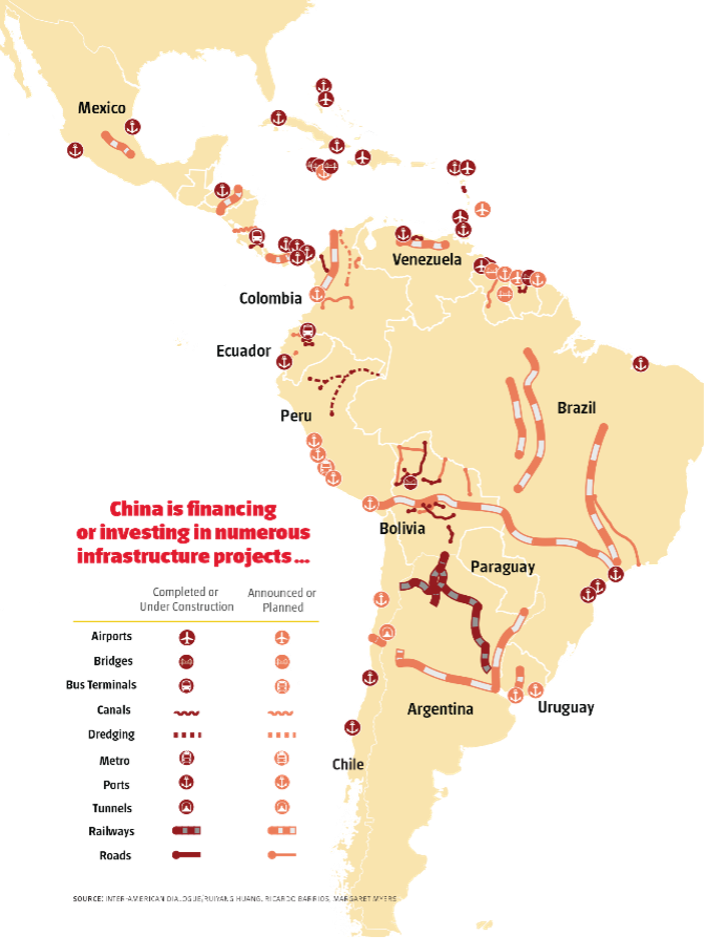

Beijing turned its attention to Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) relatively late compared to the other regions where it has been actively pursuing its geopolitical interests. Only in 2017 were LAC countries included in what the Chinese side defines as the “natural extension of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.”[22] Today, China is one of two (aside from the United States) main players in the region. In forging relations with LAC partners, the Chinese side has primarily relied on business and trade ties as well as major infrastructure projects (see below).

Source: Americas Quarterly

Beijing’s approach is slowly evolving beyond a focus on purely economic tools. China is also strengthening ties with LAC countries in defense and security, which increasingly worries Washington. Chinese PSCs are one tool Beijing has used to expand cooperation on defense and security matters. Some PSCs have taken part in certain operations across the region. As part of the paper “China in Latin America and the Caribbean: Assessing Prospects for Chinese PSCs,”[23] the following PSCs were identified as operating in LAC countries:

- China Overseas Security Group (中国海外保安集团),

- ZhongBao HuaAn (中保华安),

- TieShen BaoBiao (贴身保镖),

- China Security Technology Group (中国安保技术集团).

The activities of these entities have been sporadic and have not entailed the establishment of permanent military or security facilities. It would be fair to say that, at the time of writing, Chinese PSCs have yet to become a core element of China’s defense and security policies in LAC countries. R. Evan Ellis and Leland Lazarus noted that authoritarian regimes such as Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua would be the most likely to host Chinese PSCs. Countries with large Chinese diaspora communities, such as Peru and Panama, would presumably be open to such cooperation as well.[24] In an interview with this author, Lazarus pointed out, “As Chinese interests in the region continue to grow, more Chinese PSCs may continue to proliferate throughout LAC.”

In a video interview with this author, Ellis noted that, compared to other regions, Chinese PSCs are the “least advanced in Latin America, but what you clearly see from the Chinese-language advertisements that they put out, they are looking for opportunities.” He also suggested that the involvement of Chinese PSCs in the region will likely be seen more clearly in the next ten years: “It typically takes five to ten years from developing a need in advancing capability to getting the combination of relationships on the ground and understanding of the operating environment.”

Speaking on the United States and its approach to Chinese PSCs in LAC countries, Lazarus warned,

US analysts should be on the lookout for instances of the Chinese government using PSCs to help fulfill its overseas security interests, either by providing security or law enforcement training to local partners, facilitating weapons sales, or carrying out special security operations overseas. That change would have profound national security implications for Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States for years to come.

Ellis added, “The United States needs to continue to monitor [Chinese PSCs] and maintain a dialogue with the partner nations about it.” He also urged a stronger strategic vision when dealing with Chinese PSCs in the region, as most threats to US influence come “not so much from PSCs per se, but from potential synergies between PSCs” and other agents of Chinese influence.

Most likely, China will not prioritize the use of PSCs as its main tool for power projection in the LAC region. While the focus will be on trade, business and infrastructure projects, in terms of forging security cooperation, the Chinese side will primarily rely on contacts along the line of respective defense ministries and military training/education. PSCs, however, might be used as an auxiliary tool via forging ties with local private security providers and/or other similar agencies. Additionally, PSCs could potentially become a liaison between Chinese hi-tech companies and policing outposts established in the area.

Middle East and North Africa

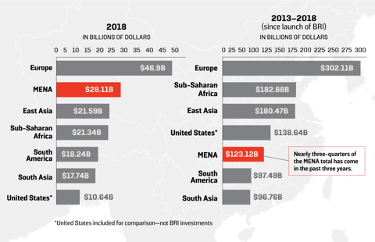

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) represents one of the last regions to make China’s priority list for expanding its economic projects. While trailing more traditional destinations for Chinese foreign direct investment, MENA now occupies a key position within the BRI. The region’s importance to Beijing notably increased between 2013 and 2018 (see below). This was mainly driven by the inauguration of two strategic initiatives: the BRI and “Made in China 2025” (中国制造2025). The national strategic plan and industrial policy aim to move China away from being the “world’s factory” toward emerging as a technologically adept powerhouse.[25] Achieving this requires uninterrupted access to critical resources such as oil and natural gas.

Source: Foreign Policy

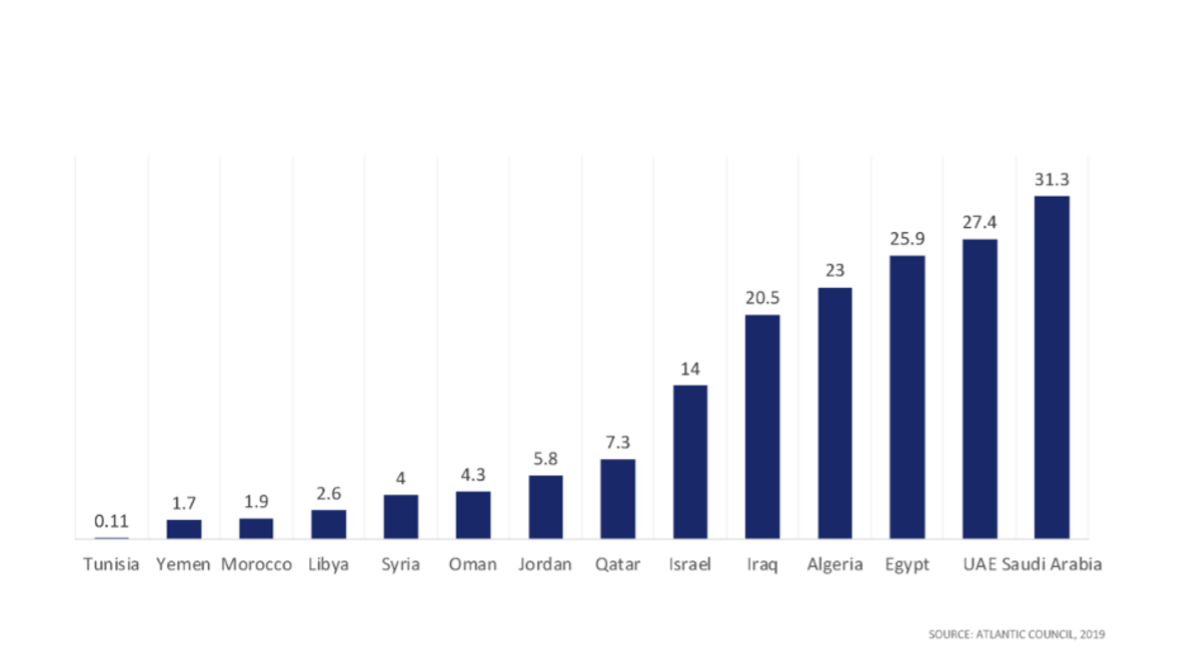

Currently, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Algeria, and Iraq are leading the region in attracting Chinese investments (see below).

Source: Atlantic Council

Chinese interests in MENA are complex and go well beyond merely natural resources or transit corridors. Beijing is also determined to forge greater cooperation in information technology, artificial intelligence, and renewable energy with the countries of the region.

At the time of writing, collaboration on defense and security matters between China and MENA countries plays a secondary role, ceding primacy to economic and business ties. It is a similar situation with private security considerations. Based on the research conducted for this project, there have been only two proven occasions in which Chinese PSCs have been deployed to MENA countries: VSS Security Group (伟之杰安保公司) in Iraq (2014) and DeWe in South Sudan (2021).[26] The number of cases is likely far greater, as several Chinese PSCs have claimed taking part in operations in the region. An in-depth analysis of open sources, however, did not provide a clear description of the roles and functions of the PSCs that reportedly took part in these operations.

Based on these results, there is little evidence to suggest that the presence of Chinese PSCs in MENA countries will dramatically increase in the coming eight to ten years.

Conclusion

Based on the overall findings of the “Guardians of the Belt and Road” project, three conclusions should be emphasized. First, the Chinese PSC industry is a relatively new phenomenon and is still in the early stages of its development. This incremental process is characterized by Beijing’s unwillingness to introduce the necessary changes to the architecture of the industry. In many ways, this impairs the level of professionalism and various functions that Chinese PSCs can perform. In the next eight to ten years, it is highly unlikely that China will alter the key operational and legislative principles underpinning the PSC industry. As a result, Chinese PSCs will not disappear, but their development is unlikely to pick up considerably for the foreseeable future. Cybersecurity and surveillance are the likeliest areas where Chinese PSCs could expand their current capabilities. These areas already play a central role in many BRI-related projects.

Second, Beijing is struggling to solve the mismatch between the geographic presence of Chinese PSCs and their ability to influence local developments. Chinese security providers have been spotted operating in nearly every major region of the world. That said, their integration and ability to promote and protect Chinese interests in specific countries and regions remains quite limited. Inherent structural deficiencies and Beijing’s caution in projecting its influence via defense and security cooperation render PSCs as marginal tools in China’s foreign policy. Moving forward, large Chinese enterprises will most likely rely on local security providers and collaboration between local officials and the Chinese government through open lines of communication between their respective defense ministries.

Third, if Beijing opts for increasing its (para)military presence, Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and MENA are typically named as the likeliest regions to see that growth. The most realistic approach would be the creation of naval bases for military-technical support (akin to the example of Djibouti) or an increased reliance on overseas police outposts. China reportedly has more than 100 police stations around the world.[27] In the latter scenario, Chinese PSCs might be deployed to serve in supplementary security roles.

In conclusion, while the use of the Chinese PSCs abroad will likely grow incrementally over the long term, the strategic importance of this trend should not be understated. The Strategic challenges posed by Chinese PSCs operating overseas is premised on the fact that these entities will be performing auxiliary functions (either independently or in collaboration with local security providers) and facilitating China’s activities in specific regions. Chinese PSCs do not possess the same skill sets, knowledge, nor experience as Western PMSCs and Russian PMCs. As a result, they struggle to carry out more complex operations. Thus, future studies pertaining to the activities of Chinese PSCs should concentrate less on (para)military activities per se. Rather, they should focus on such activities as: (a) forging ties with China’s largest tech companies and the proliferation of surveillance systems and “safe cities” projects; (b) training and working with local personnel in using drones; (c) collaborating with Chinese policing stations abroad; and (d) developments with major (deep-water) ports, which are emerging as central junctures of the BRI.

Notes

[1]For more, see https://jamestown.org/programs/gbr/

[2]Adina Masalbekova, written interview, July 24, 2023.

[3]Leland Lazarus, written interview, July 24, 2023

[4]Evan Ellis, video interview, July 27, 2023.

[5]Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan

[6] JM Foggin et al., “Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia: Anticipating Socioecological Challenges From Large-Scale Infrastructure in a Global Biodiversity Hotspot,” Conservation Letters, 2021.

[7]Sergey Sukhankin, “Tajik-Kyrgyz Border Clashes and Russia’s Limited Role: Is the Region on the Brink of Geopolitical Change?,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 18, no. 80 (May 19, 2021), https://jamestown.org/program/tajik-kyrgyz-border-clashes-and-russias-limited-role-is-the-region-on-the-brink-of-geopolitical-change/.

[8]For more information see: Sergey Sukhankin, “The Security Component of the BRI in Central Asia, Part One: Chinese and Regional Perspectives on Security in Central Asia,” China Brief, vol. 20, no. 12, July 15, 2020.

[9]China News, “专家谈中国全球战略:应东稳、北强、西进、南下” [Experts talk about China’s global strategy: it should stabilize in the east, strengthen in the north, expand in the west, and go south], December 18, 2012, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/mil/2012/12-18/4416116.shtml

[10]Sergey Sukhankin, “The Role of PSCs in Securing Chinese Interests in Central Asia: The Current Situation and Future Prospects”, February 22, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/the-role-of-pscs-in-securing-chinese-interests-in-central-asia-the-current-situation-and-future-prospects/#_ednref28

[11]Sukhankin, “The Role of PSCs in Securing Chinese Interests in Central Asia.

[12]China Security Technology Group, “保险服务” [Insurance services], accessed November 1, 2022, http://www.cstghk.com/Insurance.html.

[13]Sergey Sukhankin, “Chinese Private Security Contractors: New Trends and Future Prospects,” China Brief vol. 20, no. 9, May 15, 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-private-security-contractors-new-trends-and-future-prospects/.

[14]Aybulat Musaev, “Turkmenistan to Double Natural Gas Exports to China,” Caspian News, October 18, 2022, https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/turkmenistan-to-double-natural-gas-exports-to-china-2022-10-17-1/.

[15]Even though the Wagner Group is a quasi-PMC (effectively a mercenary army) and not a PSC, public perception of both types of entities is somewhat blurred.

[16]Sergey Sukhankin, “The Anatomy of Prigozhin’s Mutiny and the Future of Russia’s Mercenary Industry (Part One),” Eurasia Daily Monitor, July 11, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/the-anatomy-of-prigozhins-mutiny-and-the-future-of-russias-mercenary-industry-part-one/

[17]Sergey Sukhankin, “Chinese PSCs in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Anglophone Africa,” May 19, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-pscs-in-sub-saharan-africa-the-case-of-anglophone-africa/

[18]For more information, see: Sukhankin, “Chinese PSCs in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

[19]Li Qingyan, “China-Pakistan ‘Iron Brotherhood’: 70 Years Hand in Hand,” CIIS, September 8, 2021, https://www.ciis.org.cn/english/COMMENTARIES/202109/t20210908_8122.html.

[20]Sergey Sukhankin, “Chinese PSCs in South Asia: The Case of Pakistan,” July 14, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-pscs-in-south-asia-the-case-of-pakistan/#_ednref15.

[21]Umair Jamal, “Does Pakistan Have the Capability to Secure CPEC Projects?,” The Diplomat, July 22, 2022 https://thediplomat.com/2022/07/does-pakistan-have-the-capability-to-secure-cpec-projects/.

[22]Pepe Zhang, “Belt and Road in Latin America: A Regional Game Changer?,” Atlantic Council, October 8, 2019.

[23]Sergey Sukhankin, “China in Latin America and the Caribbean: Assessing Prospects for Chinese PSCs,” August 7, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/china-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-assessing-prospects-for-chinese-pscs/.

[24]Leland Lazarus and R. Evan Ellis, “Chinese Private Security Companies in Latin America,” The Diplomat, July 17, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/07/chinese-private-security-companies-in-latin-america/.

[25]Chinese Communist Party, “China to Invest Big in ‘Made in China 2025’ Strategy,” October 12, 2017, http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/ministries/2017/10/12/content_281475904600274.htm

[26]Sergey Sukhankin, “Chinese PSCs in MENA: The Cases of Iraq and (South) Sudan,” August 28, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-pscs-in-mena-the-cases-of-iraq-and-south-sudan/.

[27]Martin Pubrick, “The Long Arm of the Law(less),” China Brief, June 12, 2023, https://jamestown.org/program/the-long-arm-of-the-lawless-the-prcs-overseas-police-stations/.