Nord Stream Two: The Project’s Implications in Europe (Part Two)

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 167

By:

*To read Part One, please click here.

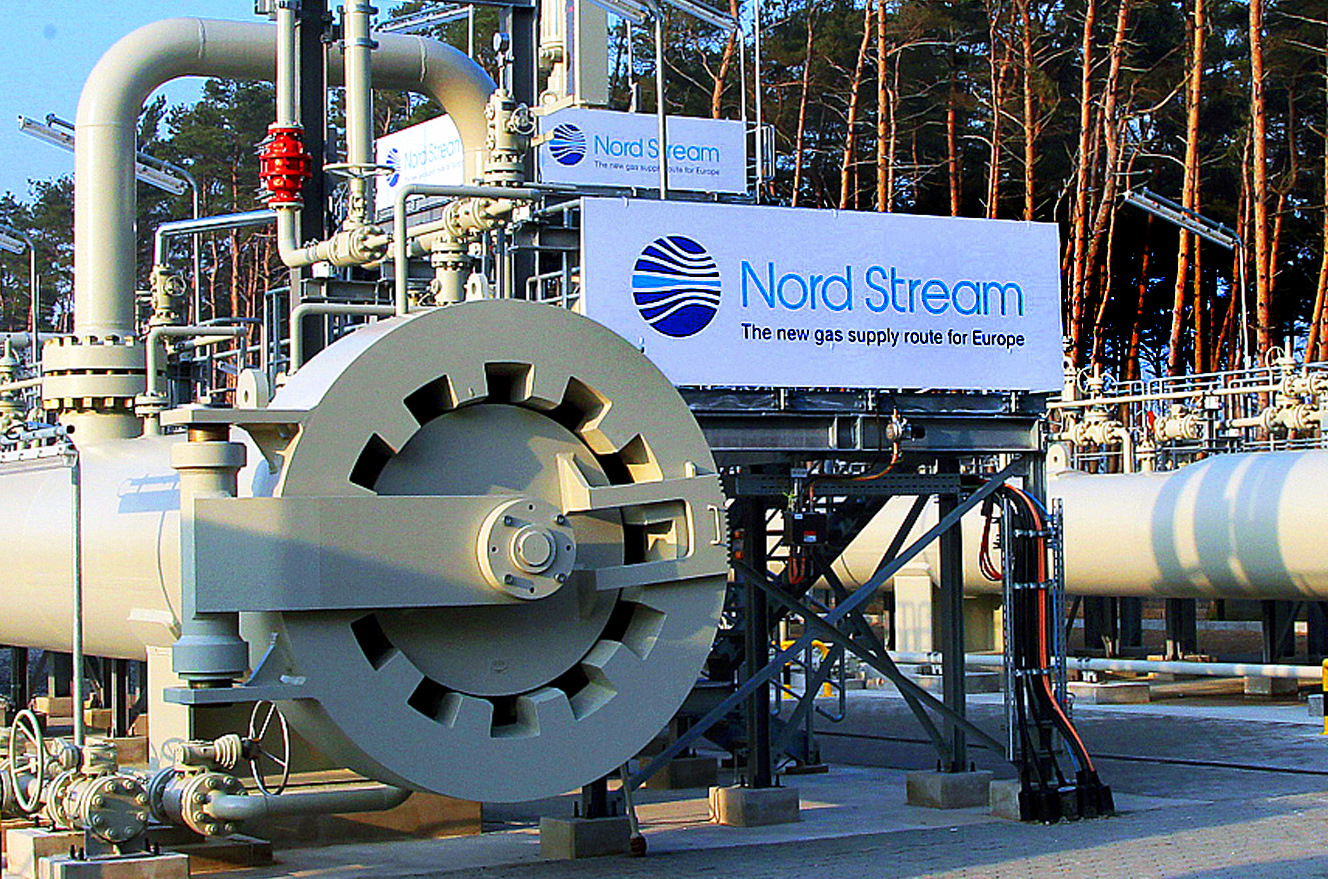

Within Germany, Nord Stream has spawned a system of gas transmission pipelines and storage sites, dedicated to handling Gazprom’s gas en route to German and other countries’ markets. That system’s ownership and operation pose serious challenges to the European Union’s energy market and competition norms. Those challenges will mount, if and when Nord Stream Two adds another 55 billion cubic meters (bcm) to Nord Stream One’s 55 bcm in annual capacity. From 2012 to date, Nord Stream One has operated at about half-capacity (see EDM, September 10, 14, 15).

The dedicated infrastructure on German territory includes the OPAL and NEL transmission pipelines and the Rehden and Jemgum storage sites, all intended to operate in conjunction with Nord Stream One and Two. Gazprom and other Nord Stream stakeholders in various combinations also own and operate OPAL, NEL, Rehden and Jemgum. Alongside that dedicated system, Gazprom and Wintershall jointly operate another gas transmission network that can also be fed with gas volumes from Nord Stream One and Two.

The European Commission had, all along, viewed those plans as aiming to create vertically integrated monopolies. The Commission used its authority and legal powers to resist such arrangements (e.g., restricting Gazprom’s use of OPAL to one half of that pipeline’s capacity). For their part, the German government and regulatory agencies allowed Gazprom to expand its pipeline and storage assets in Germany through joint ventures with German companies. A flurry of such takeovers were agreed upon in 2013 and early 2014, linked with the completion of Nord Stream One and the expected agreement to build Nord Stream Two (see EDM, January 20, 31, February 4, 5, 12, 13, 2014). Russia’s military intervention against Ukraine in February 2014, however, made it politically impossible for Germany to complete those transactions.

Germany’s time-out is now over. On September 4, Gazprom’s buyout of Wintershall’s gas trading and storage was finalized, and the Nord Stream Two shareholders’ agreement was signed. The agreement has created the New European Pipeline AG project company to build and operate Nord Stream Two (see EDM, September 10). The companies’ press releases stopped short of identifying the chief executive of the New European Pipeline AG project company. Gazprom’s photo of the signing ceremony, however, shows an uncaptioned Matthias Warnig signing the Nord Stream Two agreement, alongside the presidents/CEOs of the stakeholder companies (Gazprom.com, accessed September 14). As managing director of Nord Stream One since that project’s inception, Warnig will apparently hold the same position in Nord Stream Two. Nord Stream Two’s shareholding largely overlaps with that of Nord Stream One and with the shareholdings of the dedicated onshore pipelines and storages in Germany.

These actions are already accompanied by pressures from the interested companies and the German government to override EU energy market and competition legislation. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble apparently proposes transferring some of the European Commission’s anti-trust competencies to other authorities, not publicly specified as yet. Germany’s own anti-trust and regulatory agency, the Bundesnetzagentur, does not object to Gazprom’s monopolistic use of the OPAL and (in prospect) NEL pipelines (Naturalgaseurope.com, September 3).

According to the European Commission, the offshore Nord Stream One was implemented in line with EU law at that time, but “the Commission will ensure that Nord Stream Two, if implemented, fully complies with the EU’s Third Package of energy legislation.” And “any pipelines, whether northern or southern, on EU member countries’ territories must be fully compliant with EU legislation (Bloomberg, UNIAN, September 11). This official statement alludes, first, to the fact that the Third Package was not yet in force when Nord Stream One was built, but has entered into force since then. It further alludes to the European Commission’s effective use of EU law to block South Stream—that other Gazprom-led project in Europe.

The European Commission’s vice-president for the Energy Union, Maros Sefcovic, has announced “a host” of questions to be raised on Nord Stream; e.g., Does it correspond with the EU’s supply diversification strategy? What does it mean for Central and Eastern Europe? What conclusions should be drawn, if this project aims practically to shut down Ukraine’s transit route? “All projects of this magnitude would have to comply with EU legislation,” he declared (Politico.eu, September 7, 11; UNIAN, September 11; BTA, September 15).