While Moscow Could Not Afford It, China Will Build Railway North to Sakha

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 41

By:

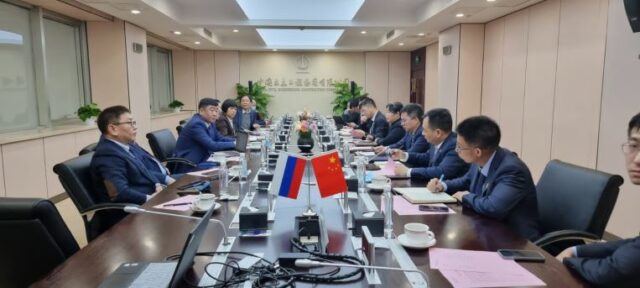

In early March 2023, at a meeting in Harbin, Chinese officials committed Beijing to building a railway north from China into the enormous and resource-rich Sakha Republic that dominates the Russian Far East—yet is rather far from the Chinese border (Promvest.info, March 8; Kolyma.ru, March 9). The session did not lead to the announcement of either a precise route or schedule for the construction of this line, with the two sides only committing themselves to establishing both in the near future. And perhaps for that reason, thus far, this event has attracted little attention in the Russian media; but it represents a potentially transformative event for the region, China and the Russian Federation.

First, the proposed line would extend China’s infrastructure reaches far deeper into Russian territory than ever before. Up to now, China has focused on areas just north of the border or along existing Russian routes, such as the Trans-Siberian line. Beijing has built bridges and opened factories just north of the border but generally avoided going deeper into Russia’s interior. Second, China and Sakha appear to have reached this agreement on their own having met several times over recent months to discuss how it could be achieved. This came after Moscow declared last summer that it did not consider the route a priority (Vesma.today, June 22, 2022), a euphemism for the Kremlin not having enough money for such a project given the costs of its war against Ukraine (Svpressa.ru, June 9, 2022; February 19; Profile.ru, December 22, 2022). Third—and this may matter the most over the long haul—the route will be built on the basis of concessions in which China will gain long-term access to the natural resources in the region in exchange for building a railroad Russia could not afford.

In the short term, this new Chinese initiative will benefit Moscow and especially those Russian firms and officials who control the natural resources in Sakha by promoting increased exports to China (see EDM, February 25, 2020; June 16, 2022). Putin may even welcome it because it means he can still talk about what he describes as Russia’s “turn to the east.”

But in the longer term, such a route will tie Sakha specifically and the Russian Far East more generally far closer to Beijing than to distant Moscow and raise the specter in the minds of many Russians that China is becoming the paramount power in the region. And this could eventually be the case even if China does nothing to change the political borders between itself and the Russian Federation—a classic form of neo-colonialism that Moscow is accustomed to denouncing in others but often fails to see China is using that same approach within Russia’s current borders. This state of affairs gives Beijing all the benefits it wants without being forced to absorb the social welfare costs of absorbing additional territory and population (see EDM, May 6, 2021; February 1, 2022; Kasparov.ru, January 30). Railway projects, such as the latest one to Sakha, are far more significant than merely the appearance of Chinese maps of Siberia and the Russian Far East showing historical Chinese names for places there, though such maps invariably attract far more attention in both Moscow and the West.

At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that, even with Chinese resources behind it, the construction of a railway between China and resource-rich Sakha will not be easy nor happen overnight. Most of the route will pass through areas without any roads or population centers. And this will force the Chinese to bring in materials and labor from the outside, raising the specter of Chinese “guest workers” in Russian land far from the Chinese border where they have become commonplace. At best, construction will likely take several years.

On that point, the history of railway construction east of the Urals is not encouraging. Moscow has regularly started and then stopped building lines because of the difficulties involved (Window on Eurasia, June 4, 2022). And China faces an additional challenge at the northern end of the prospective line: the rapid melting of permafrost will require either massive investment in freezer technology to keep the line from collapsing or the prospect that the route will have to be repaired constantly. Those problems have plagued Russian construction efforts in recent years, and China will not be able to avoid them or their costs (see EDM, July 6, 2021; Bellona.ru, November 2, 2021).

But because China wants the timber, coal and other minerals that Sakha can provide, Beijing is far more likely to persevere in the construction of this project—at least far more than Moscow has. And that in and of itself will echo far beyond the borders of even the Sakha Republic. It may very well suggest to the leaders and peoples of the Russian republics and regions east of the Urals that they too should follow Moscow’s advice and look “east” rather than “west.” But for them, doing so would mean looking away from Moscow and toward Beijing. To be sure, this is hardly what Vladimir Putin hopes for but is yet another example of how his war against Ukraine has triggered counterproductive consequences far from the battlefield.